Background: People who inject drugs (PWID) are at high-risk for developing serious injection related infections requiring long-term IV antibiotic therapy. For infective endocarditis, current guidelines recommend at least 4 to 6 weeks of IV antibiotic therapy. In PWID, it is recommended this be completed in a supervised setting because discharge home with a PICC line for outpatient IV antibiotic therapy may be complicated by social determinants of health that can limit adherence in this population, among other potential risks. For many PWID, remaining inpatient for the duration of their antibiotic therapy is a difficult commitment and leads to disproportionate rates of discharge before medically advised (BMA). Emerging data suggests prescription of contingency antibiotics including long-acting injectables and oral options at the time of BMA discharge reduces morbidity and mortality when compared to those who leave without antibiotics.

Purpose: The aim of this initiative is to increase documentation of antibiotic contingency plans and their prescription at the time of BMA discharge.

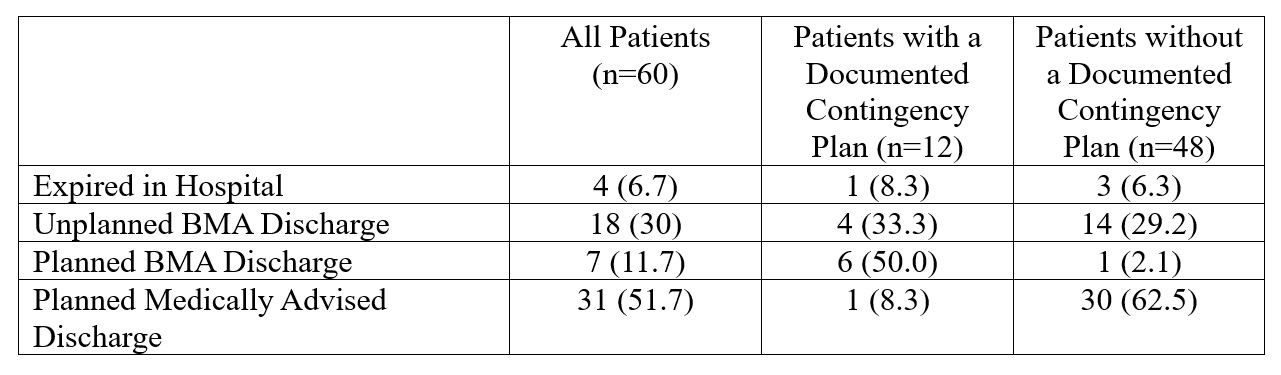

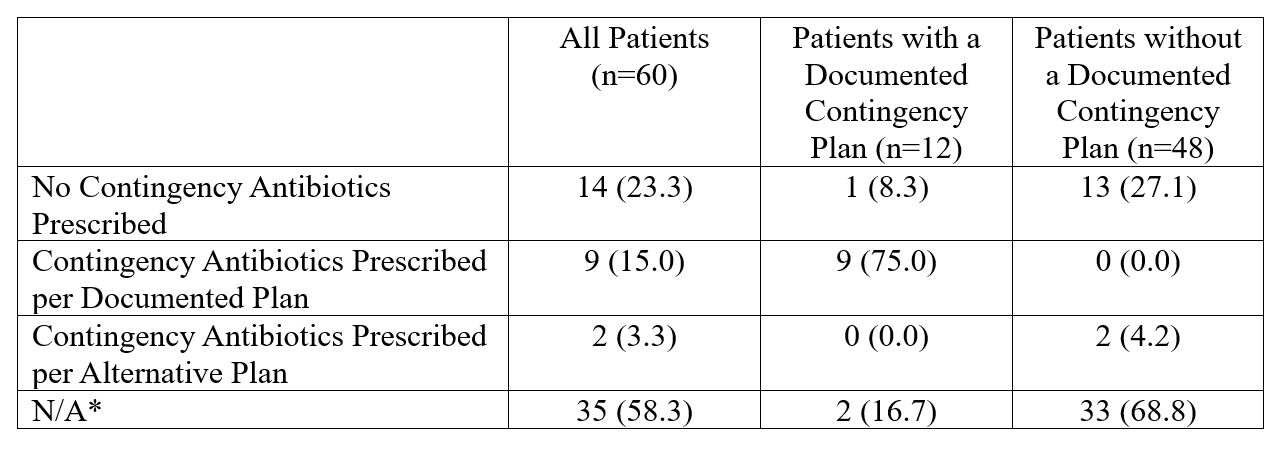

Description: Using a custom RedCap tool, we completed a pre-intervention chart review of all patients admitted between 2020 and 2022 with infective endocarditis and IV drug use (past or present). We captured patient demographics, the presence or absence of a documented antibiotic contingency plan, BMA vs planned discharge, and if a contingency plan was enacted and completed. In total, 60 patients were included. 25 patients left the hospital BMA prior to completion of IV antibiotic therapy. 12 patients had documented contingency antibiotic plans, of which 10 left BMA. Of those patients with a documented contingency plan who left BMA, 9 were prescribed contingency antibiotics according to the documented plan. 48 patients did not have a documented contingency antibiotic plan, of which 15 left BMA, and of those only 2 were prescribed contingency antibiotics. Patients consistently expressing a desire to leave BMA were more likely to have documented contingency plans. Those with documented contingency plans were significantly more likely to have contingency antibiotics prescribed on BMA discharge compared to those without documented plans. Based on post-discharge documentation, 7 of 11 patients prescribed contingency antibiotics on BMA discharge completed the prescribed course. A multi-modal intervention is underway including both educational and electronic health record (EHR) initiatives. Educational initiatives include a lecture series targeted toward internal medicine faculty, fellows, and residents that will appear at Medicine Grand Rounds, Hospital Medicine Continuing Medical Education, and Resident Didactics. Within our EHR, we are piloting a SmartPhrase to be used by primary inpatient teams and infectious disease consultants to guide comprehensive contingency planning in case of BMA discharges in PWID. A survey assessing knowledge and perception of contingency antibiotic planning is also underway.

Conclusions: PWID frequently leave the hospital BMA and are more likely to be discharged with a contingency antibiotic plan if it is documented during the admission. We are hopeful that with comprehensive education and standardized documentation we can increase our rate of contingency antibiotic documentation and prescription. Once we have completed the intervention period, we will collect post-intervention data to determine our degree of improvement.