Background: To address the risk of missed or delayed diagnoses, organizations need to identify and learn from their diagnostic opportunities. However, current approaches to identifying diagnostic opportunities are insensitive, resource intensive and often have low yield.(1,2) Evaluation of diagnostic trajectories can highlight diagnostic opportunities. For example, a patient may re-present to the healthcare system with serial complaints of abdominal pain, weight loss, and ultimately hematochezia before being diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Such a situation may represent an opportunity to perform diagnostic colonoscopy earlier.

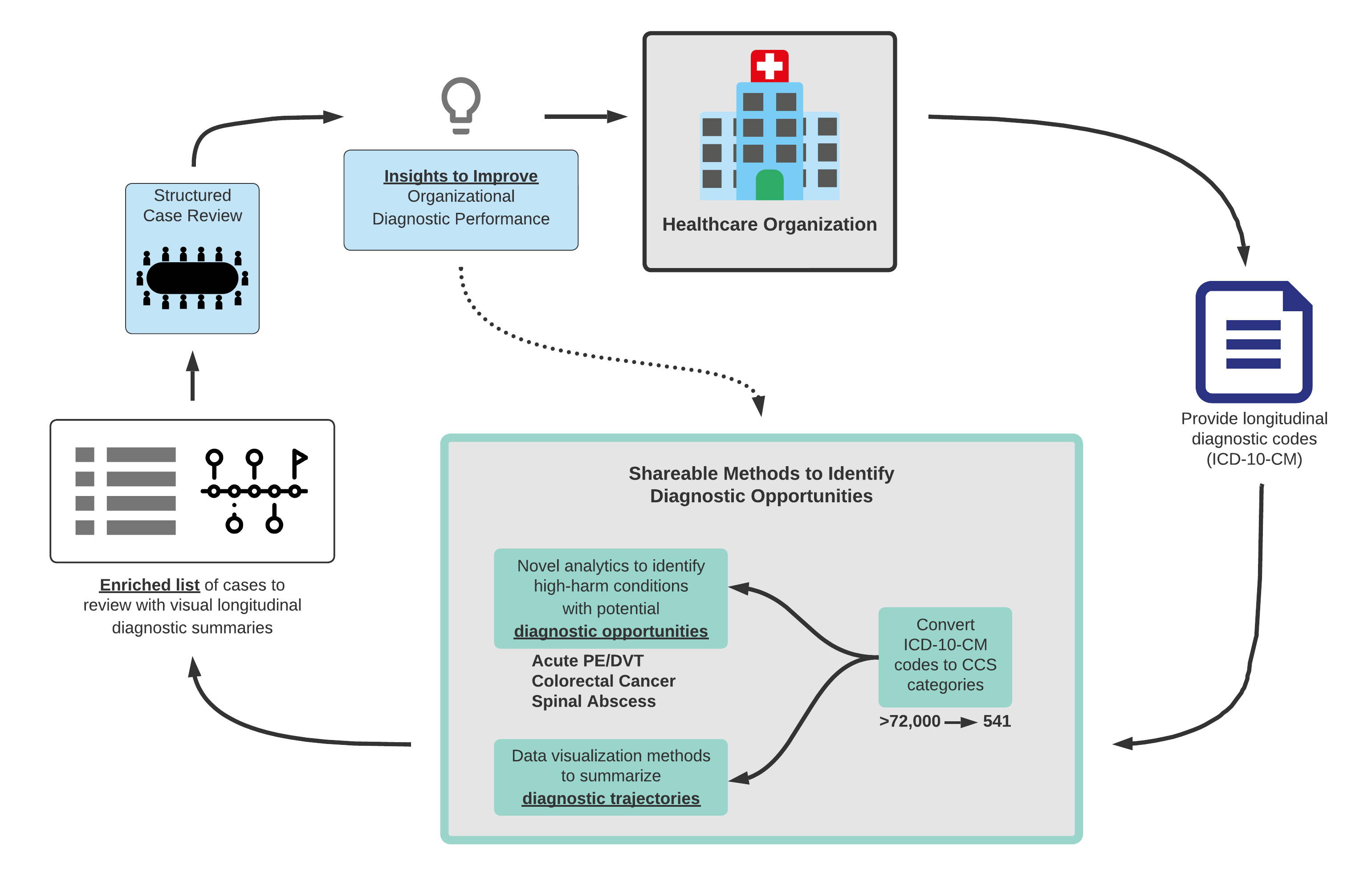

Purpose: We aimed to develop and pilot tools that analyzed diagnostic trajectories to: 1) help organizations identify which cases were more likely to represent diagnostic improvement opportunities; and 2) provide case-specific summaries to support efficient case review (Figure 1). We piloted these tools on new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC), venous thromboembolism (VTE) and spinal abscess (SA).

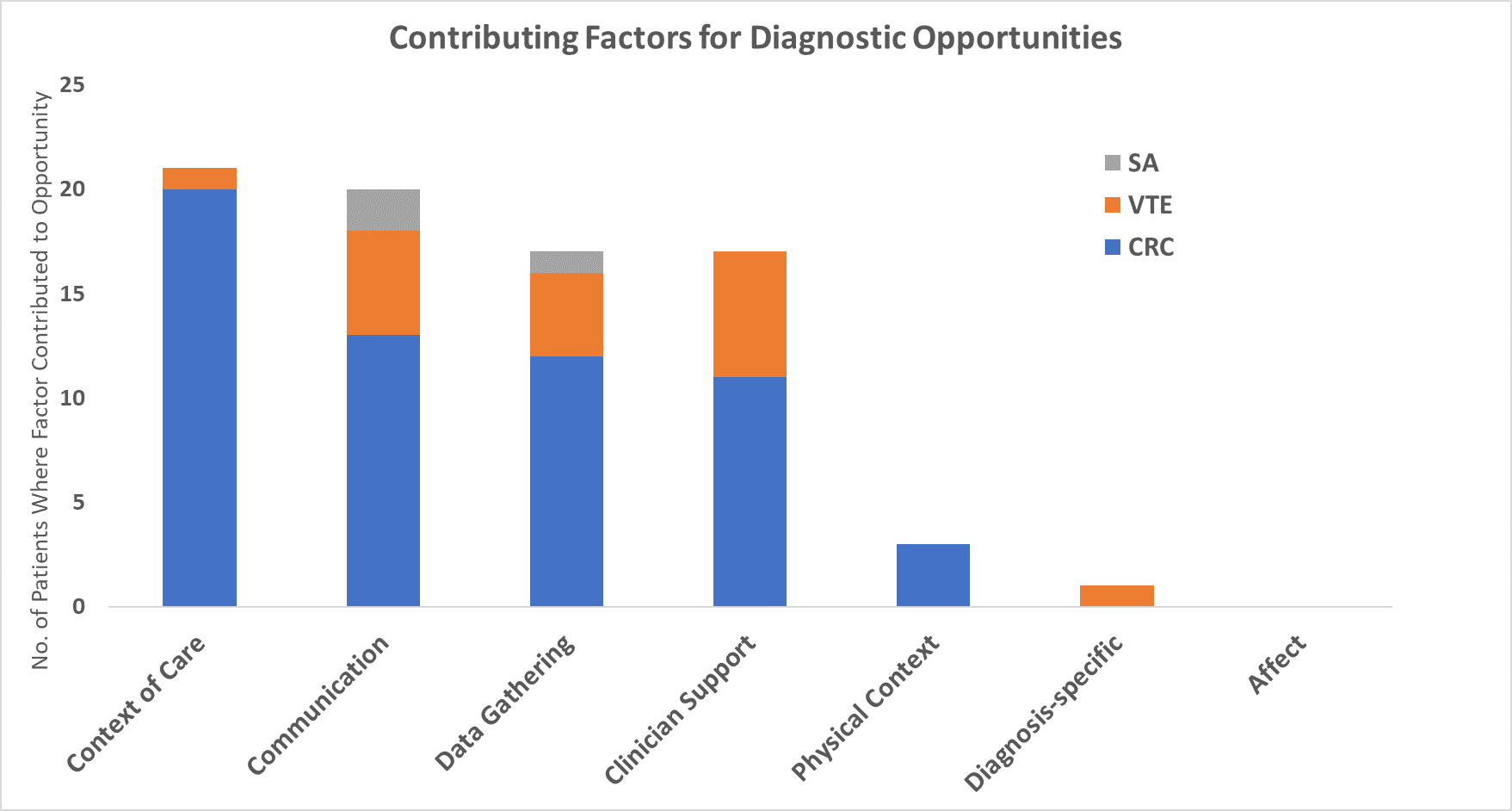

Description: Algorithm Development: We analyzed diagnostic trajectories between 1/1/2011 through 11/9/2020. We developed three methods to identify cases that warranted structured case review; Method 1—identifying new diagnoses (to that patient) in a prespecified look-back period prior to the target diagnosis; Method 2—logistic regression-based; and Method 3—neural network/AI-based.Automated case summarization: We created and iteratively modified case summaries to facilitate efficient case review. Structured diagnostic case reviews: We performed multi-disciplinary structured diagnostic case reviews for a sample of cases of our target conditions. We used REDCap and the SaferDx screening tool to screen for diagnostic opportunities and Reilly’s framework to describe contributing factors and areas of improvement.(3, 4, 5)Results: Method 1 yielded opportunities in 33 of 91 (36%) CRC cases, 7/52 (13%) of VTE cases, and 5 of 26 (19%) SA cases. Method 2 and 3 generally had better performance for identifying opportunities for VTE and SA cases.For Method 2, the predictors of new diagnoses associated with identification of the target conditions were generally consistent with known associations. For example, CRC was associated with new diagnoses of acute pulmonary embolism, gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage and nutritional anemias. VTE was associated with GI and other cancers and SA with osteomyelitis, epilepsy and traumatic brain injury.Case reviews identified actionable diagnostic improvement opportunities: Case reviewers identified several diagnostic improvement opportunities across multiple domains (Figure 2). Our team escalated some of these opportunities to the appropriate leaders in our organization. Specific examples included improvement of alternative methods for CRC screening; appropriate follow-up of microcytic anemia; and population health team support to ensure appropriate follow-up (e.g., tests, referrals).

Conclusions: We connected novel case identification and summarization tools with a structured diagnostic case review process to facilitate organizational learning from diagnostic improvement opportunities. All three methods showed promise in using longitudinal sets of diagnostic codes to identify cases with opportunities and are superior to random chart review which traditionally only identifies opportunities in 3% – 5% of reviewed charts.(1,2)