Background: Black patients have been shown to have worse physical function, higher likelihood of developing mobility limitations and higher rates of mobility loss and functional decline. Despite these functional disadvantages, Black patients are less likely to receive acute and post-acute rehabilitation services. These disparities have been described in community-dwelling, ambulatory, and surgical populations, and social disparities in functional recovery have been shown in the intensive care setting. However, no studies have assessed whether these differences exist in patients on Hospital Medicine services. We aimed to assess differences by race and social disadvantage in functional outcomes and physical therapy (PT) referrals in patients on Hospital Medicine services.

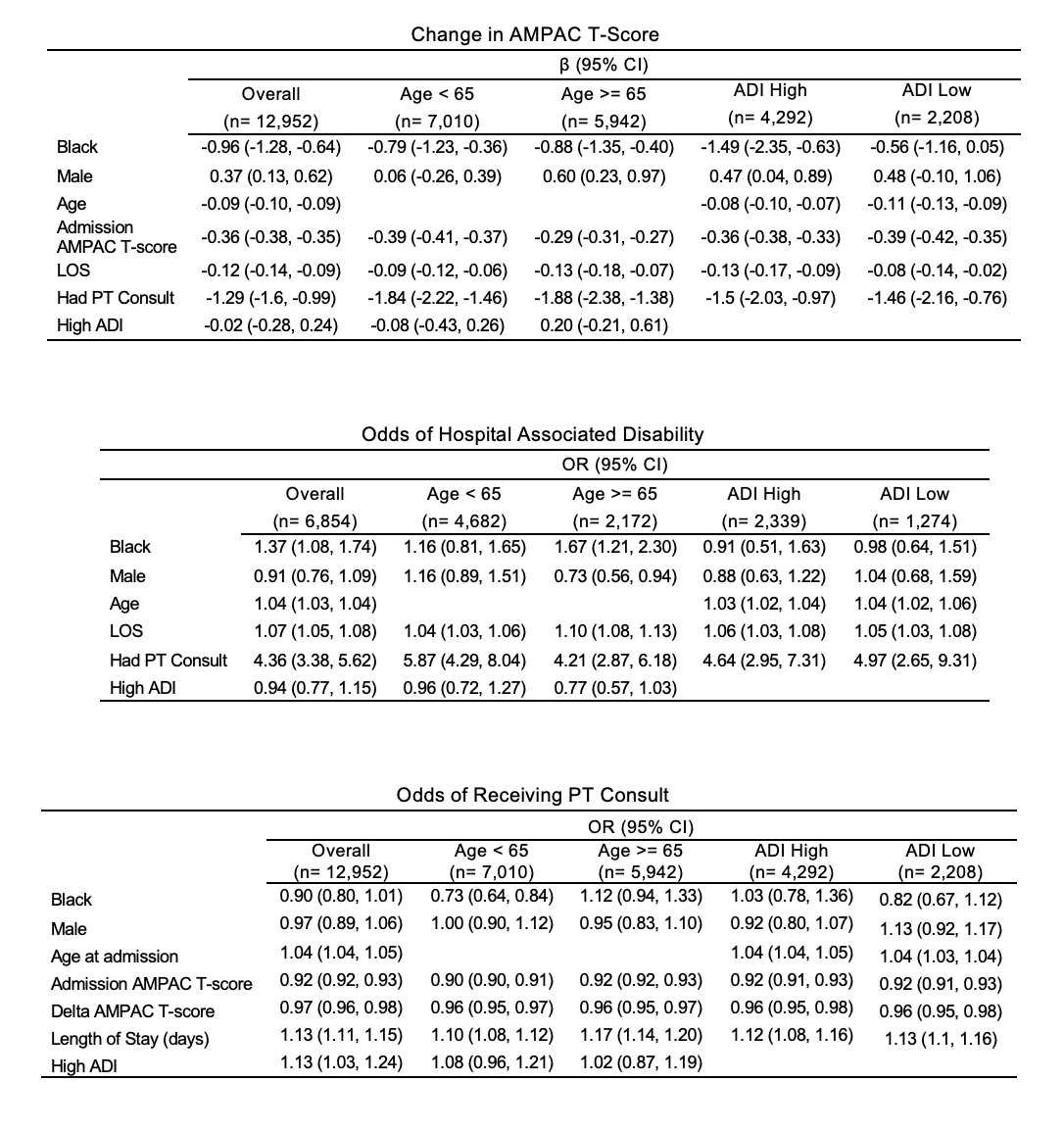

Methods: We analyzed admissions lasting > 48 hours on Hospital Medicine services between 1/1/18 – 5/6/22 at a large tertiary academic hospital. Baseline characteristics were compared using chi-squared or t-tests. Regression analysis was used to test for the association of Black race with 1) receipt of an inpatient PT consult controlling for age, sex, length of stay, admission mobility score, mobility change (delta AMPAC = discharge AMPAC T-score – admission AMPAC T-score), and receipt of PT referral; HAD development controlling for above covariates excluding delta AMPAC; and mobility change using above covariates. We adjusted for social disadvantage using the Area Deprivation Index (ADI). We performed subanalyses by age (< 65 vs ≥ 65), functional impairment on admission (AMPAC ≤ 18 vs > 18), and social disadvantage [high (deciles 8, 9, or 10) vs low (deciles 1, 2, or 3)].

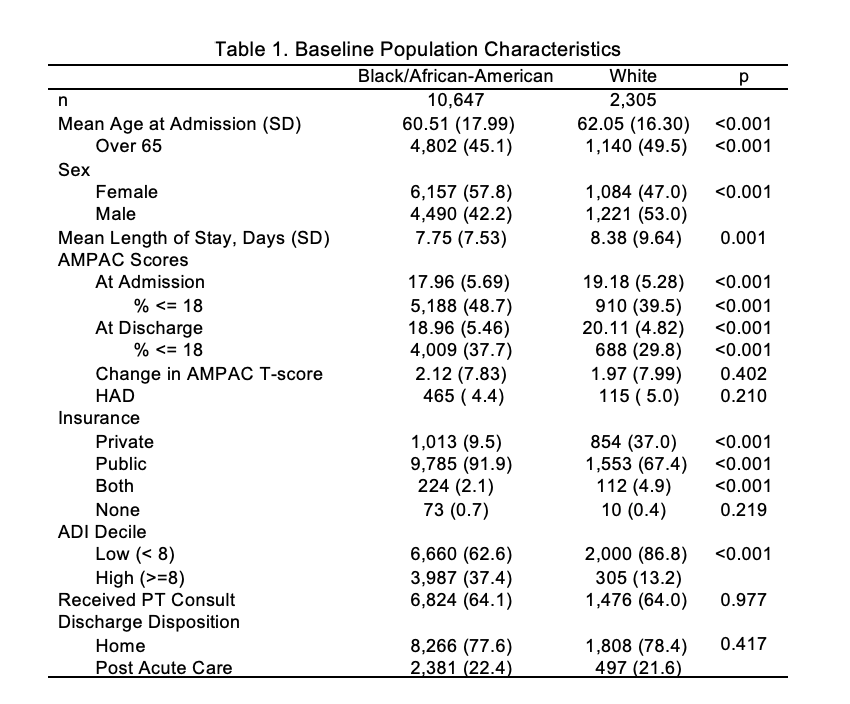

Results: Patients were predominantly Black (82.2%). Black patients were younger (60.5 vs 62.1 years old), more likely to be male (53% vs 42.2), to reside in a neighborhood with high social disadvantage (37.4% vs 13.2%) and had lower mobility scores at admission (18 vs 19) and discharge (19 vs 20). In unadjusted analyses, there was no statistically significant difference in rates of inpatient PT consults, HAD, or mobility change by race. In adjusted analyses, Black race was associated with a negative effect on mobility change during hospitalization [β -0.96; 95% CI (-1.28, -0.64)]. The effect of Black race was strongest among those with high social disadvantage [β -1.49, 95% CI (-2.35, -0.63)]. In mediation analysis, receipt of a PT consult minimally mediated the effect of Black race. The direct effect of Black race was -0.96 (95% CI [-1.28, -0.63]), but the indirect effect through the mediator (PT consult) was 0.03 (95% CI [0.01, 0.06]), making the total effect -0.93 (95% CI [-1.25, -0.600). Black race was associated with higher odds of HAD [OR 1.37, 95% CI (1.08, 1.74)]. The association was stronger for those ≥ 65 [OR 1.67, 95% CI (1.21, 2.30)].Black race was not associated with receipt of a PT referral except in those < 65 [OR 0.73; 95% CI (0.64, 0.84)]. There was no significant association between Black race and HAD or PT referrals in subanalyses of the highest or lowest ADI deciles.

Conclusions: Black race and social disadvantage may increase risk of poor functional outcomes in patients on Hospital Medicine services. Groups presenting with or at risk for developing more functional impairment should be prioritized for PT referrals. Hospitalists and those creating inpatient mobility protocols should consider these risks to help guide the decision to refer patients for physical therapy during hospitalization.