Background: Prognostic risk scores allow clinicians to rapidly identify patients with acute pulmonary embolism (PE) at a low risk for mortality and morbidity. Current guidelines recommend that these patients be considered for outpatient treatment. Despite this, most patients with low-risk PE are still hospitalized for monitoring and initiation of anticoagulation. Interventions to improve provider awareness have been shown to increase outpatient treatment; nevertheless a significant evidence-practice gap remains. Our present aim is to characterize the prevalence of low-risk PE in the Emergency Department (ED) at a tertiary care center and describe the disposition outcomes of acute PE diagnoses.

Methods: We identified all cases of acute PE diagnosed in the ED from July 2016 through March 2018 using ICD-10-CM codes. We excluded patients in whom the diagnosis of PE was made after the decision to admit to an inpatient service, or those with a co-existing diagnosis (e.g. sepsis) justifying inpatient admission. For all cases included in our analysis, we obtained baseline demographics and comorbid conditions, as well as physical examination, laboratory and radiographic findings available upon presentation to the ED. We then extracted disposition outcomes, length-of-stay (among hospitalized patients), and choice of anticoagulant. Patients were characterized as either low- or high-risk PE based on their simplified PE severity index (sPESI) score (i.e. a sPESI score of 0 versus ≥1, respectively). Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare both groups, with a significance level of 0.05.

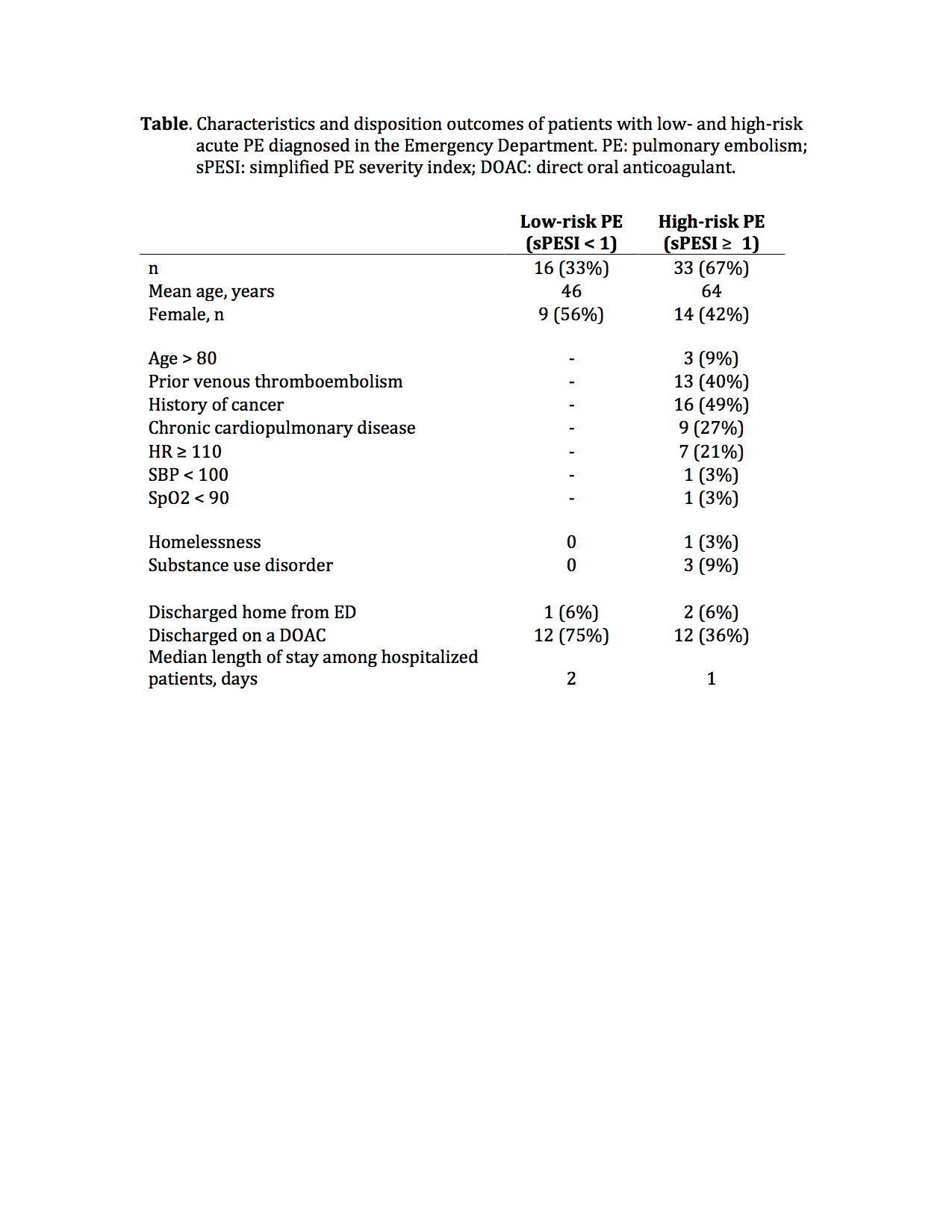

Results: One hundred and ninety eight cases of acute PE were diagnosed in the ED from July 2016 through March 2018. Of these, we reviewed a random sample of 49 patients. Thirty three percent were characterized as low-risk based on their sPESI score. Among this low-risk group, no contraindication to outpatient treatment could be identified on chart review in 75% of cases. However, only 6% of all low-risk PE patients were discharged from the ED for outpatient initiation of therapy (Table). No significant difference was observed in length of stay among low- and high-risk patients admitted to the hospital. Low-risk patients were most likely to be started on a direct oral anticoagulant (p = 0.02).

Conclusions: The rate of low-risk PE diagnosed at our tertiary care center is similar to that reported in the literature, and in most cases no contraindication to outpatient treatment initiation is documented. Despite this, outpatient treatment is rarely pursued, and the vast majority of low-risk PE patients are admitted to the hospital. There remains a significant evidence-practice gap in the management of low-risk PE.