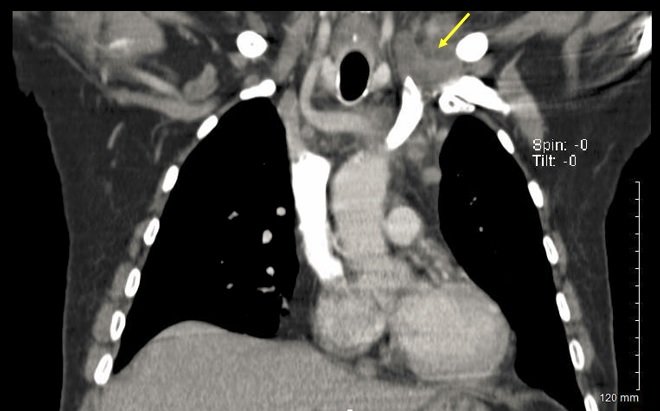

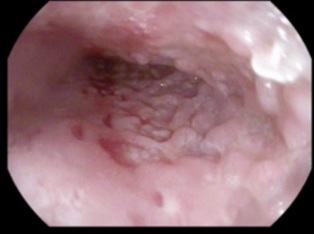

Case Presentation: A 69 year-old Mexican man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented to the hospital for fever and dysphagia of 4 weeks duration. CT of the chest taken at an outside facility showed a large esophageal mass with right hilar and left supraclavicular lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). Given concern for malignancy, an EGD with biopsy was performed which showed a large, fungating mass in the middle and lower third of the esophagus highly concerning for an esophageal tumor (Figure 2). Pathology demonstrated denuded squamous mucosa with no immunophenotypic evidence of malignancy, and was negative for CMV, HSV 1/2, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining. Despite these results, index of suspicion for malignancy (from the standpoint of oncology, infectious disease, gastroenterology, and pathology) was still high and a core biopsy of the enlarged supraclavicular lymph node was performed. Pathology of this second biopsy was again unrevealing, showing no evidence of malignancy or infection. As the patient continued to spike high fevers, further infectious work-up was completed. Cryptococcal and histoplasma antigens, as well as antibodies against coccidioides, brucella, and bartonella were all negative. The initial T-Spot taken at admission was borderline, as was the repeat T-Spot. About one week into admission, a microbial cell-free DNA next-generation sequencing test was sent from tissue of the supraclavicular node biopsy, which later returned positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The biopsy from the final EGD stained positive for AFB, as did 2 of 3 subsequent sputum cultures. Our final diagnosis was fever of unknown origin secondary to esophageal tuberculosis, and RHZE therapy was initiated with improvement in both dysphagia and the fever curve.

Discussion: Anchoring bias is among the most common cognitive biases in medicine, and it leads to premature closure of both the diagnosis and treatment plan. At the beginning of this case, the patient’s history and imaging pointed in the direction of an esophageal malignancy – a likely diagnosis which was validated by multiple consultants. However, as time passed, both new information and the patient’s clinical course began to deviate from what would be expected if the initial diagnosis were true. Despite this new data, it took nearly 2 weeks to initiate therapy for extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. In part, this delay resulted from a failure to appropriately re-frame new information. In remaining fixated on dysphagia in an older male with a history of substance abuse, lymphadenopathy on CT, and a large fungating mass on EGD, we failed to consider other salient features of the case. Namely, the patient was from a TB endemic area, had persistent high fevers, had multiple biopsies that were negative for malignancy, and had multiple indeterminate T-Spots. In 2012, Ogdie and colleagues described the various contexts in which cognitive errors such as anchoring bias most commonly occur. In particular, “team factors” such as reliance on multiple consultants were the most-cited contextual cause of bias. In our case, this too was certainly a prominent barrier to making the appropriate diagnosis.

Conclusions: As hospitalists, we know the big picture of our patient’s care better than anyone else. Thus, as new information becomes available or as the patient’s clinical status deviates from the expected path, take a cognitive “time-out.” Re-formulate the problem representation using all newly available data, and discuss this re-frame with your consultants.