Background: Increased Emergency Department (ED) boarding has been linked to worse patient outcomes, including delays in treatment (Jiraporn et al 2014), increased length of stay (Singer et al 2011), and increased mortality (Singer et al 2011; Sun et al 2013). Patients who meet time zero (T-0) for diagnosis with severe sepsis while boarding in the ED may not receive appropriate care and suffer worse outcomes. Our goal was to determine the association between ED boarding and sepsis bundle compliance and mortality among patients with community acquired sepsis.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with community-acquired sepsis (defined by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance criteria) who were admitted to a large academic hospital in the U.S. from July 2021 to September 2023. Community-acquired sepsis was defined as meeting T-0 (defined based on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Sepsis 1 (SEP-1) guidance) within 48 hours of admission. The primary outcome was SEP-1 bundle compliance (antibiotics, blood culture, fluid bolus and lactate measurement). Secondary outcomes were compliance with individual SEP-1 bundle components and hospital mortality. We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test, Fisher’s exact test, and chi-square tests to compare differences between patients who were under ED care versus ED boarders, as well as the subset of patients who received antibiotics after T-0. We used logistic regression to estimate the association between ED boarding status and SEP-1 compliance adjusting for a priori identified covariates of age, presence of heart failure or kidney disease, and presence of shock.

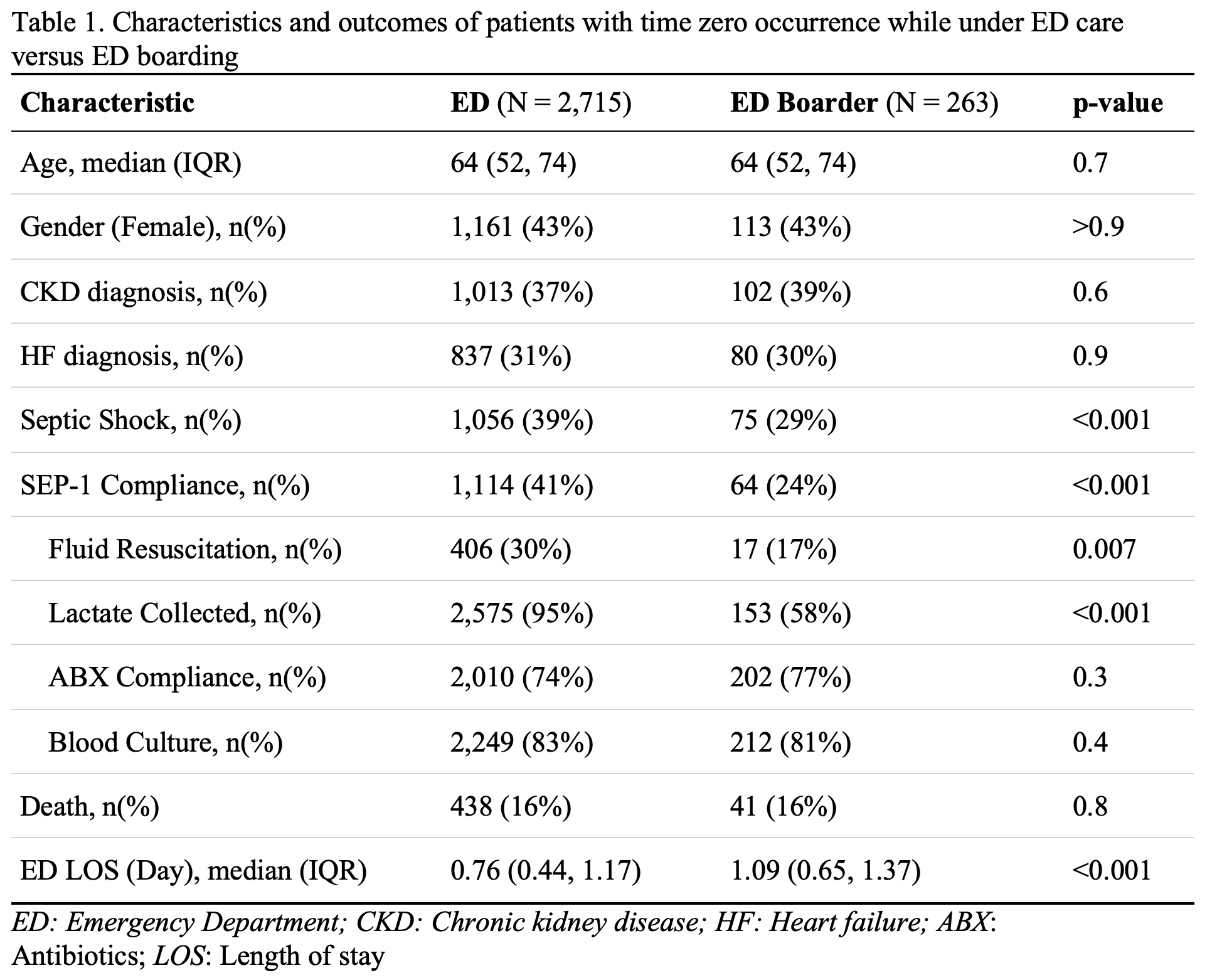

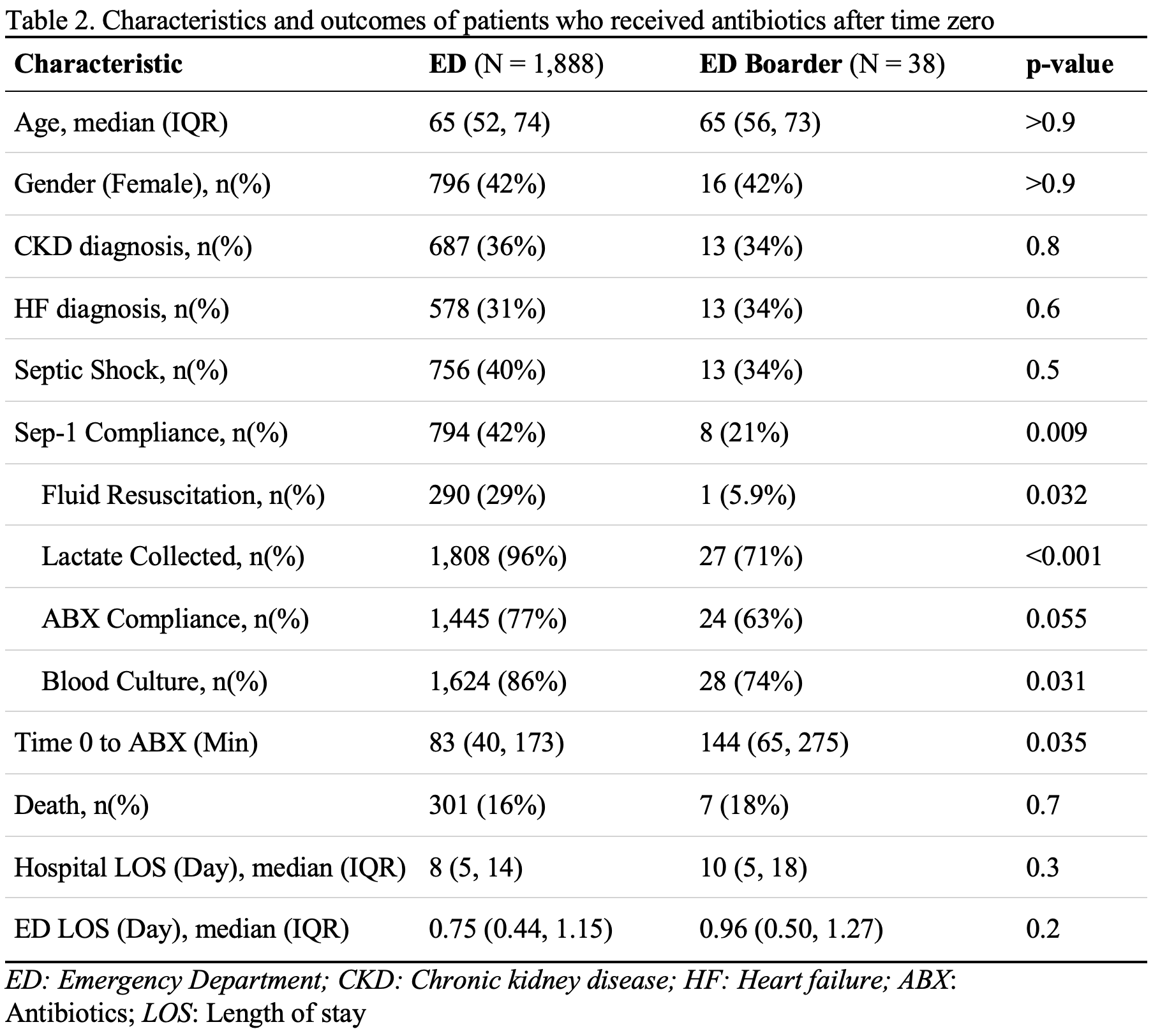

Results: Out of 2,978 patients meeting T-0 while in the ED, 263 (9%) met T-0 as an ED boarder. Table 1 shows characteristics and outcomes for patients meeting T-0 as ED boarders versus still under the care of the ED. Groups were similar in age, gender, and comorbidities, but a lower proportion of ED boarders had a diagnosis of shock (29% vs 39% p< 0.001). Fewer ED boarders received SEP-1 Compliant care (24% vs 41%, p< 0.001), including lower proportions of fluid resuscitation (17% vs 30%, p=0.007) and lactate measurement (58% vs 95%, p< 0.001). Antibiotic compliance was similar between the two groups (77% vs 74%, p=0.3). Adjusting for confounding variables, experiencing T-0 as an ED boarder was associated with decreased odds of SEP-1 compliance (adjusted OR 0.42 [95% CI: 0.31-0.57], p< 0.001), with no difference in hospital mortality (adjusted OR 0.95 [95% CI: 0.66-1.34], p=0.8). 225 (85%) patients in the ED boarding group and 827 (30%) in the ED care group received antibiotics before meeting T-0. Excluding patients who already received antibiotics before meeting T-0, ED boarders waited longer to receive antibiotics (144 min vs 83 min, p=0.035; Table 2).

Conclusions: Patients who meet T-0 for community-acquired severe sepsis while boarding in the ED have lower rates of SEP-1 compliance, including being less likely to receive fluid resuscitation, lactate and blood culture collection, and wait significantly longer to receive antibiotics. Although mortality rates were not different between ED boarders and patients under ED care, it is important to improve the quality of sepsis care provided to ED boarders.