Background: The extent and impact of bias in medicine are increasingly recognized. Studies have demonstrated the deleterious effect of clinicians’ biases on patient care (1,2), and the impact of patients’ biases on physicians’ well-being (3). We hypothesized that more subtle expressions of bias would increase burnout among academic hospitalists. The objectives of this study were to assess the frequency of experienced or observed bias among members of a large, academic, multidisciplinary hospitalist group, and to characterize the impact of these experiences on burnout.

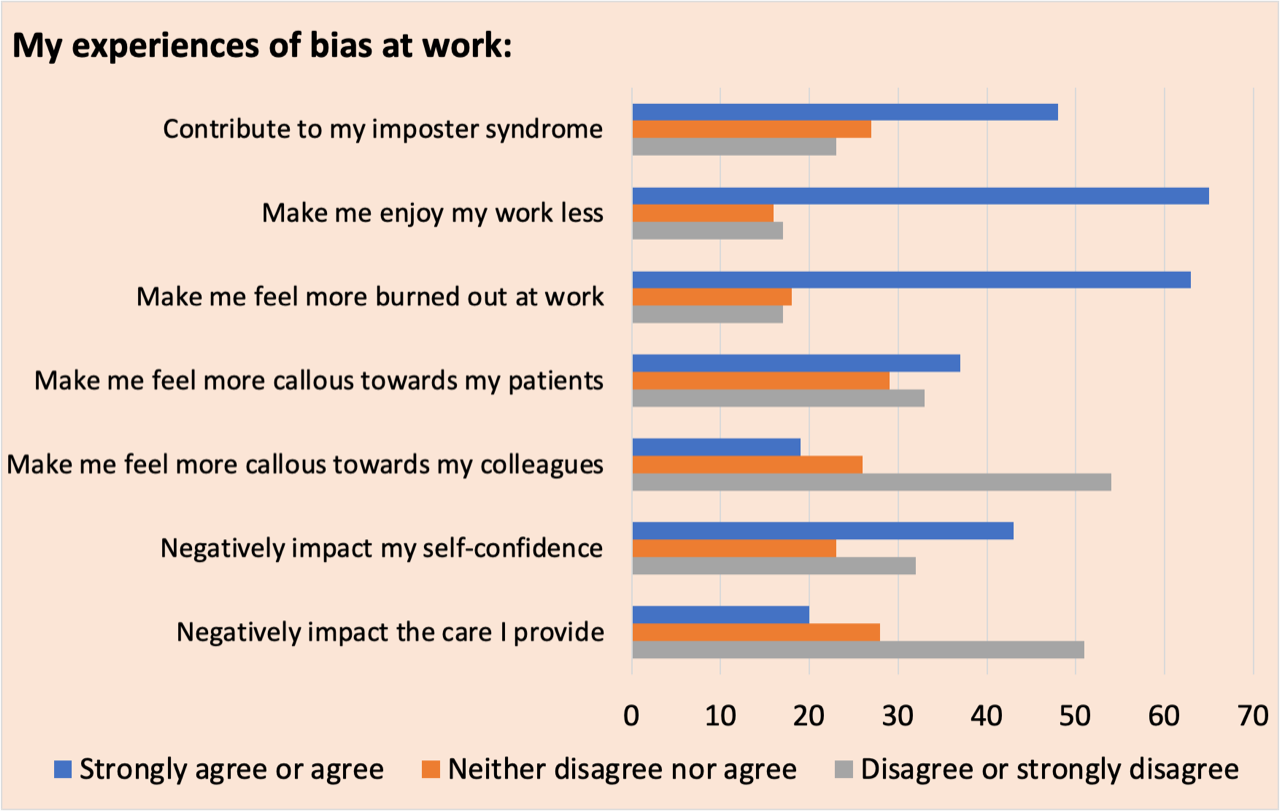

Methods: We surveyed hospitalists at a large, urban, academic medical center using a 30-item instrument, including questions from the Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey (4) and tools developed by the authors. Participants rated their agreement with statements such as “My experiences of bias at work contribute to my imposter syndrome,” “My experiences of bias at work make me enjoy my work less” and “My experiences of bias at work make me feel more burned out at work.” All hospitalists (MD/DOs and advanced practice providers [APPs]) were eligible; participation was voluntary. The survey was administered using RedCap and was accessible from 2/1/2022 to 3/21/2022. Participants received a $5.00 gift card. The study was deemed exempt by the Mass General Brigham IRB.

Results: Of 145 eligible hospitalists, 103 (71%) completed the survey. Respondents were cisgender female (67%), cisgender male (29%), and “other” or “prefer not to say” (4%); and as Asian (22.3%), Black (4%), Latinx (5%), White (62%), and “prefer not to say” (9%). Most participants (62%) had completed training in the prior five years. Both APPs (30%) and physicians (70%) participated. Hospitalists endorsed experiencing bias frequently, reporting gender bias (62% of respondents), racial bias (30% of respondents), and other forms of bias, including bias “based on gender identity or expression, perceived sexual orientation, body habitus, age, accent, country of origin, socioeconomic status” (50% of respondents). Few participants reported consistently addressing bias with the source (11%). Over half of respondents reported observing bias directed towards others. Only 36% of respondents “often” or “always or almost always” debriefed with targeted colleagues after observing expressions of bias. While patients and visitors were the most common source of bias/microaggressions, non-hospitalist co-workers, consultants, and hospitalist colleagues were also sources of bias. Hospitalists connected their experiences of bias at work with burnout. Specifically, 46% of respondents endorsed that bias experienced at work contributed to imposter syndrome. Sixty three percent reported it led to enjoying work less, 61% linked it to burnout, 41% said bias negatively impacted their self- confidence, and 36% reported it driving callousness towards patients.

Conclusions: In this study, we identified high rates of bias experienced and observed by physician and APP hospitalists at a large academic institution. Respondents identified experiences of bias as contributors to burnout. These results align with our prior work on trainees’ experiences of bias (5). These results underscore the critical need to address the impact of bias in hospital medicine, and the importance of providing both individual and system-level interventions (6). Further study is needed to understand how to manage these encounters in a multidisciplinary setting, and to assess the longer-term impact on hospitalists.