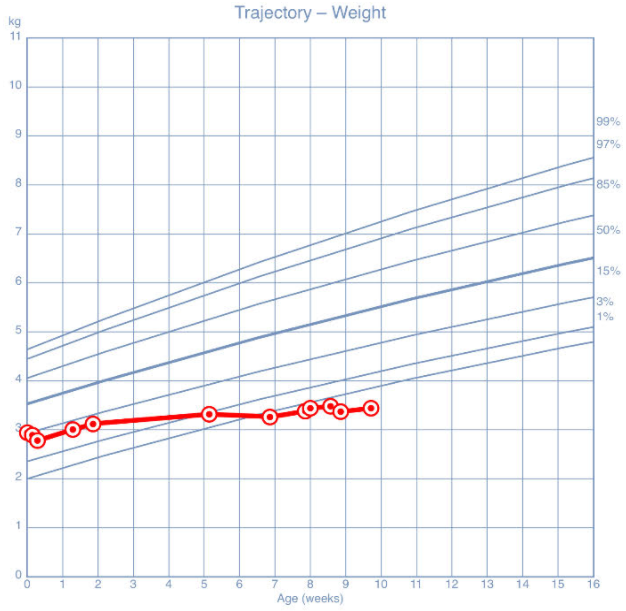

Case Presentation: A 7-week-old male was admitted to a children’s hospital by his pediatrician due to “failure to thrive” (FTT). He was born full-term, passed his critical congenital heart disease (CHD) screening, and had normal newborn screens. He was exclusively breastfed and regained birthweight by 9 days of age. Over the subsequent weeks, his parents had concerns that he was feeding frequently but briefly and was “fussy” afterward. They reported no choking, apneas, emesis, or change in stools. By 5 weeks of age, growth had slowed to 9 g/day (Fig. 1). By 7 weeks of age, parents were concerned about intermittent tachypnea, without fever or cough. On physical examination, respiratory rate was 56 breaths/min, blood pressure (BP) and pulse oximetry in the right lower extremity were 85/56 mm Hg and 99% respectively. A 2/6 systolic murmur was auscultated at the left sternal border, and equal femoral pulses were palpated. Chest X-ray demonstrated moderate cardiomegaly with prominent pulmonary vasculature. After consulting a cardiologist, a reliable BP in the left upper extremity was found to be elevated, 120/80 mm Hg. Echocardiogram confirmed enlarged ventricles and severe coarctation of the aorta (CoA), in addition to a large ventricular septal defect (VSD) and questionably patent ductus arteriosus. The patient was transferred from the general pediatric service to the cardiac care unit given the potential for decompensation to ductus-dependent circulation. Despite a persistent BP differential, he remained non-acidotic so prostaglandin infusion was deferred. Computed tomography angiography requested by the cardiothoracic surgeon confirmed postductal CoA (Fig. 2). Aortic arch advancement and VSD repair was performed. Postoperatively, there was no BP differential between radial and femoral arterial lines. He recovered well from surgery and was discharged home on furosemide and enalapril, with feeds of fortified breastmilk to promote catch-up growth.

Discussion: The patient’s tachypnea in the absence of respiratory distress prompted a stepwise workup that resulted in a diagnosis of CoA with VSD leading to heart failure and severe malnutrition. Due to varying severity of CoA lesions, affected infants may have normal femoral pulses, as was documented in this patient’s birth records and subsequent hospitalization for FTT. As illustrated here, CoA is the critical CHD that most often has false-negative screening results. Acknowledging that valid BP measurements are difficult to obtain in infants, the right upper extremity remains the gold standard location from which to attempt measurement. Obtaining four-extremity BPs may have prompted an expanded workup sooner. If technique is appropriate, a gradient of over 20 mm Hg between upper and lower extremities suggests narrowing of the aorta. As in this patient, over half of children with CoA will have additional cardiac abnormalities, primarily bicuspid aortic valve or VSDs, that may require lifelong management by a cardiologist.

Conclusions: The differential diagnosis for FTT is broad and jointly requires detailed history-taking and objective longitudinal data. As information became available, hospitalization, subspecialist involvement, and escalation of care was provided in a safe and timely manner. This case should remind providers that congenital heart disease should remain on the differential diagnosis for FTT despite normal newborn CHD screening, palpable distal pulses, and reassuring initial growth parameters.