Background: Management of the hospitalized cancer patient represents unique challenges: delivery of complex, specialized medical management to a growing population, compounded by intense scrutiny of patient preference and goals of care. Historically, these patients have been admitted to a subspecialist’s service, but many institutions have now transitioned to a hospitalist-driven care model. Limited research suggests that some hospitalist-led teams may provide oncology patients with inpatient care comparable to that of a subspecialized oncologist.1,2 Despite this broadening of scope, there is little research regarding the educational backgrounds that hospitalists managing subspecialty patients receive and importantly, no specification of training characteristics that make a hospitalist-run subspecialty program successful. We seek to characterize hospitalists’ perspective on oncology-specific education and care delivery by employing a web-based survey. We hypothesize this study will identify a baseline deficiency in hospitalists’ oncology education and management confidence.

Methods: An IRB-approved, web-based survey was sent to hospitalists at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center to assess their training/experience with oncology patients and comfort level with specialist collaboration. Demographic/practice characteristics were also gathered. Eligible participants were Attending Physician hospitalists with the opportunity to provide clinical care to cancer patients.

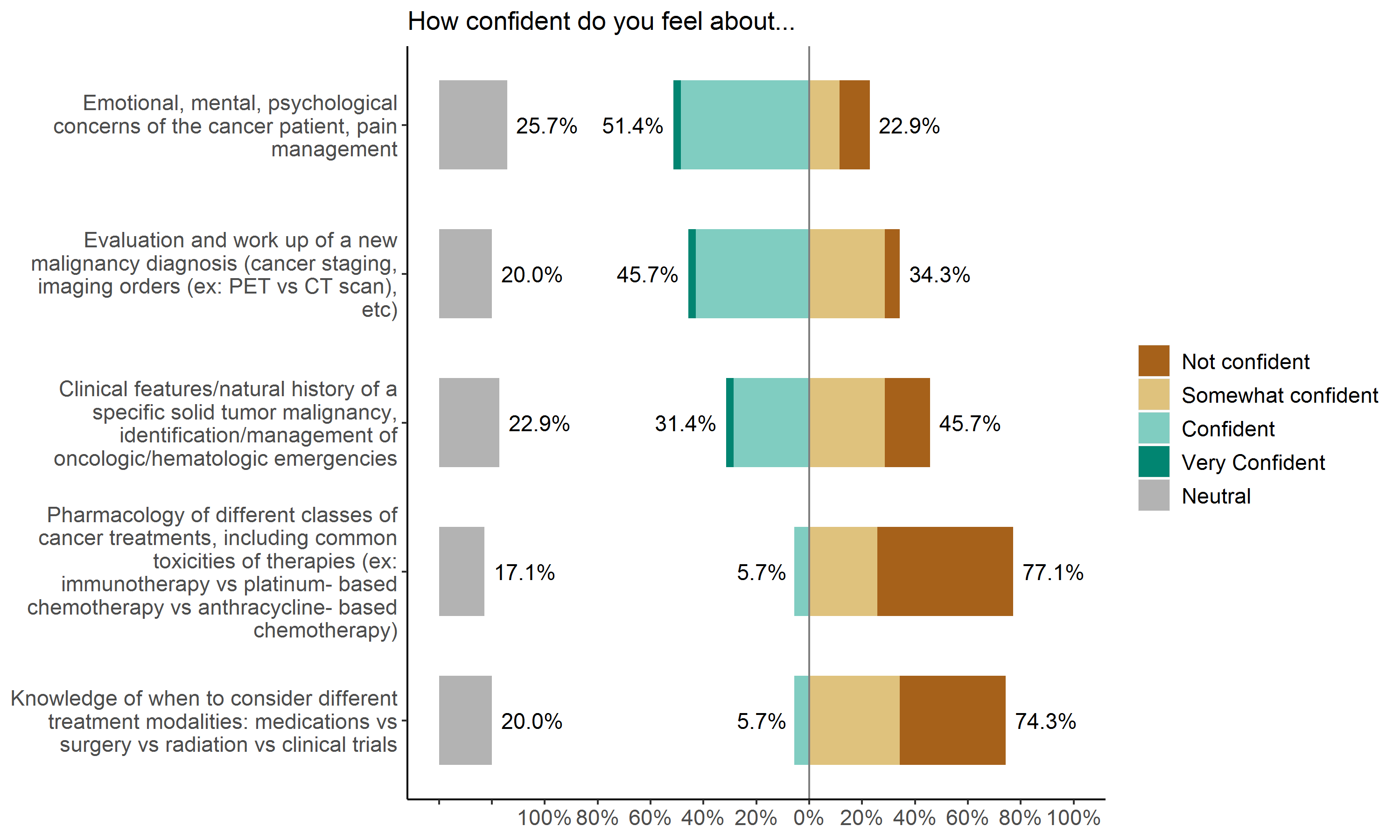

Results: A total of 102 participants met eligibility criteria and were sent the web-based survey; 35 participants have completed the survey to date. The majority of participants have only internal medicine training; twelve (34.3%) have practiced as an Attending Physician for 0-3 years, ten (28.6%) for 4-7 years, and thirteen (37.1%) for over 7 years. Regarding their oncology experience, the majority (60%) of hospitalists on a scale of 1 (none/not confident) to 5 (extensive/very confident) endorsed they had only some (2) prior training/education on cancer-related topics. The majority (34.3%) expressed confidence (4) caring for patients with cancer, but 31.5% felt only somewhat or not confident (responding 2 or 1, respectively). Most (37.1%) reported feeling not confident (1) addressing cancer therapy side effects. Most (40%) also reported that they did not directly interact with a patient’s primary oncology team often (1). Finally, respondents otherwise felt not confident or only somewhat confident (1 or 2) about: selection of different cancer treatment modalities (74.3%), pharmacology of different classes of cancer treatments (77.1%), and clinical features of a specific solid tumor malignancy or management of an oncologic emergency (45.7%). See Figure 1.

Conclusions: To our knowledge, this survey is the first of its kind to provide a critically needed perspective on current hospitalist-led subspecialty management and faculty preparation for specialty care delivery. The majority of participants self-identified multiple gaps in their education or experience related to the care of cancer patients. Communication with the primary oncology team may also be improved. We believe that targeted interventions to address these self-reported deficiencies will translate into overall improved subspecialty patient outcomes. As a pilot intervention, an inpatient oncology-focused educational curriculum will be delivered to the described study population in the near future.