Background: Oral case presentations are a core learning opportunity for students, during which they synthesize data, develop assessments and plans, and communicate clinical reasoning. However, during focus groups at our institution, faculty and students described presentations as inefficient, redundant, and lacking standardized expectations. Faculty were overall dissatisfied with student presentations. Students described presentations as stressful and not useful for learning or patient care. Thus, we created and assessed a novel curriculum for oral presentations. Our goals were to strengthen students’ skills, establish shared expectations, and create opportunities for practice and feedback.

Methods: Using Kern’s six steps to curriculum development, we created a curriculum to teach students to deliver presentations that are Structured, Timed, Applicable, and Reasoning-focused (STAR). A three-part intervention was implemented for faculty and students on the inpatient medicine service from August 2022 – December 2023. 1) An online resource folder with guidelines and templates for presentations was shared with faculty and students. 2) At the start of the clerkship, students participated in an 80-minute workshop, during which they learned the STAR framework, practiced a presentation, and used a rubric to give peer feedback. 3) Lastly, there was a mid-clerkship check-in session to answer students’ questions about presentations. To evaluate the intervention, pre-STAR surveys were administered in Spring 2022 to faculty and students who had recently rotated on the inpatient medicine service. Post-STAR surveys were collected during the intervention period, immediately after participants’ time on service (10-day rotations for faculty, 8-week clerkships for students). Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, Wilcoxon rank sum test, and Fisher’s exact test.

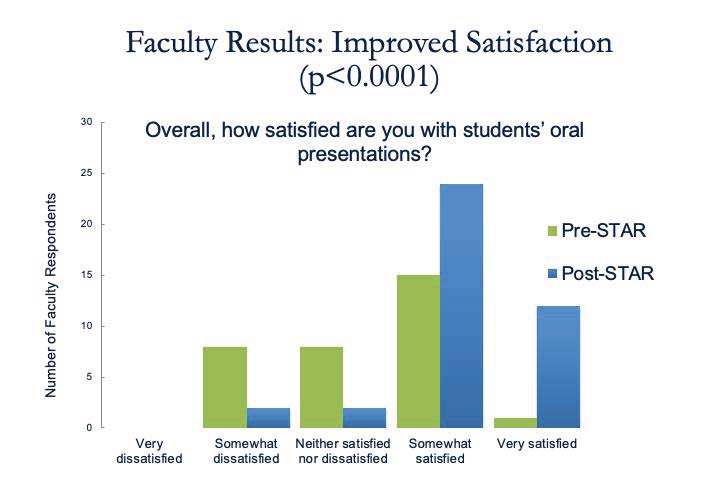

Results: For faculty, survey response rates were 39% (32/83) pre- and 58% (45/77) post-STAR. The majority reported reviewing the STAR resources (76%) and agreed the resources were useful (64%). Post-intervention, faculty noted an improvement in the clarity of expectations for presentations (p< 0.0001) and were more satisfied with presentations overall (p< 0.0001, Figure 1). Faculty perceived an improvement in students’ ability to identify relevant information to present (p=0.0208) and were less likely to report that presentations were way too short or way too long (p=0.0091). For students, survey response rates were 59% (13/22) pre- and 36% (24/66) post-STAR. The majority reported reviewing STAR resources (76%) and agreed that the resources (84%) and workshop (76%) were useful. Almost all students (91%) reported that the intervention helped them understand expectations for presentations. 57% reported that STAR provided a framework for them to seek feedback and 48% noted that STAR created more consistent expectations. Post-intervention, students reported more frequently receiving feedback about presentations (p=0.0027, Figure 2).

Conclusions: The majority of faculty and students agreed the STAR curriculum was useful for teaching and learning presentation skills. Faculty noted improvements in clarity of expectations, students’ skills, and presentation length. Students reported increased frequency of feedback about presentations. A next step is to characterize the quality of feedback provided.