Background: Hospitals increasingly face capacity strain and challenges with patient flow, leading to emergency department (ED) crowding, ED boarding, and threats to patient safety and quality of care. ED boarding occurs from the time of the decision to admit until the patient arrives in an inpatient bed and is affected by many factors including discharge time, inpatient bed vacancy, inpatient room turnover, transport availability, and staffing. At our institution, admitted patients were not assigned an inpatient bed until full admission orders were placed, leading to concern that delayed orders contributed to ED boarding. We aimed to implement an intervention to hasten bed assignment and measure its impact on time of patient arrival in an inpatient bed.

Methods: We created a brief bed request order that prompted bed assignment, independent of full admission orders. This order included information on a patient’s level of care and need for isolation, continuous pulse oximeter or telemetry monitoring, or safety attendant and could be ordered with information obtained from a conversation with the ED provider and/or a brief chart review. Admitting hospitalists and medicine residents were trained in use of the new order, which was implemented in November 2021. Data was obtained from the electronic health record via Clarity for the pre-intervention (November 2020 to October 2021) and post-intervention (November 2021 to October 2022) periods. Data was analyzed using an interrupted time series analysis (ITS) and T-tests. Time to arrival in an inpatient bed was measured as the duration from the decision to admit until ED departure. Time to inpatient bed assignment—the time from decision to admit until an inpatient bed was assigned—was also measured as a component of the overall time to arrival in an inpatient bed.

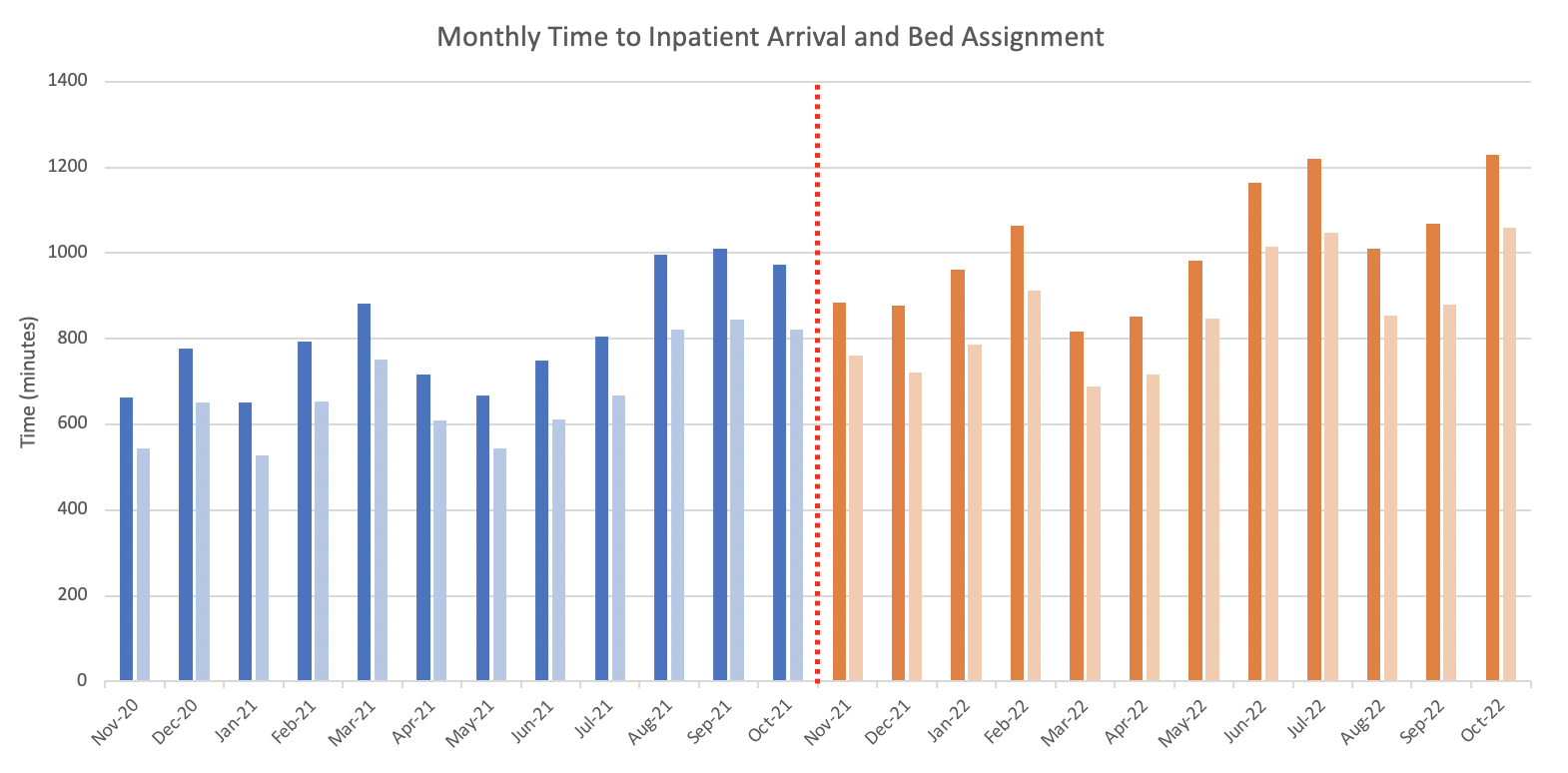

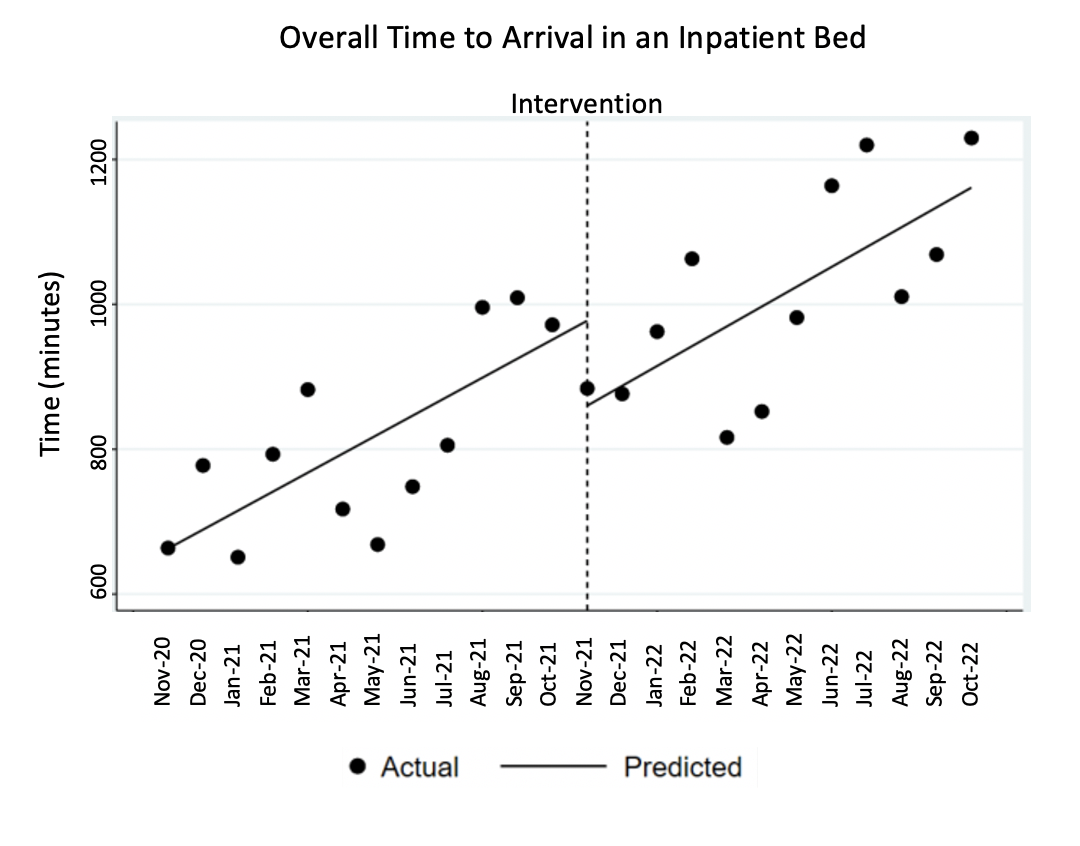

Results: A mean of 551.9 medicine patients were admitted per month pre-intervention and 588.2 patients were admitted per month post-intervention (p=0.01). Overall use of the bed request order was 85.6%. Mean overall time to arrival in an inpatient bed was 807.0 minutes pre-intervention and 1010.8 minutes post-intervention (p=0.001), and mean time to bed assignment was 670.7 minutes pre-intervention and 857.4 minutes post-intervention (p=0.001) (Figure 1). ITS showed a significant increase in the overall time to arrival in an inpatient bed by 26.3 minutes/month (p < 0.001) pre-intervention and by 27.38 minutes/month (p < 0.001) post-intervention; this difference was not significant (p = 0.88) (Figure 2). Post-intervention, time to arrival in an inpatient bed was similar between patients with and without use of the bed request order (1014.0 vs 1010.8 min, p=0.70) with similar results for patients in acute, transitional, and intensive levels of care. Time to bed assignment post-intervention was 858.7 minutes for patients with a bed request order and 847.5 minutes for patients without the order (p=0.85), with similar results for acute, transitional, and intensive care patients.

Conclusions: A bed request order, independent of full admission orders, placed by admitting hospital medicine teams did not reduce the overall time to inpatient bed assignment or arrival in an inpatient bed. Uptake of order use following implementation was high. Lack of improvement after the intervention may have been due to confounding factors including an increase in the overall numbers of admissions, increasing levels of ED crowding, and staffing challenges. Further efforts are needed to meaningfully reduce ED crowding and patient wait times.