Background: Effective provider communication improves patients’ satisfaction, engagement, and health outcomes. Sitting at the bedside may improve communication; however, many providers do not regularly sit during inpatient encounters. We conducted a controlled pre-post evaluation of adding wall-mounted folding chairs inside the entrance of patient rooms, coupled with education, to increase sitting at the bedside by internal medicine residents at a large, academic hospital.

Methods: During 9/2019 – 1/2020, prior to adding folding chairs to rooms, we surveyed patients on 4 general medical units, each unit home to a “firm” to which residents are randomly assigned at the start of training. Eligible patients were hospitalized >2 days and had to identify, from a face sheet, the resident whose behavior was being considered. Patients completed separate surveys about first-year residents and upper-year residents on their care team. Surveys assessed the frequency of sitting and of other communication behaviors (e.g., spending enough time at the bedside, checking for understanding). In 2/2020, we added the folding chairs to 2 firm units (chosen prior to baseline survey collection) and conducted educational activities for all 4 firms. Because of the COVID pandemic, we delayed post-intervention surveys until 10/2021 – 4/2022, and after a repeated round of education in 9/2021. Survey outcomes were assessed as means on Likert-type items with 1 being “never” and 5 being “every single time.” We compared differences between groups using repeated-measures ordered logistic regression to adjust for multiple surveys per resident.

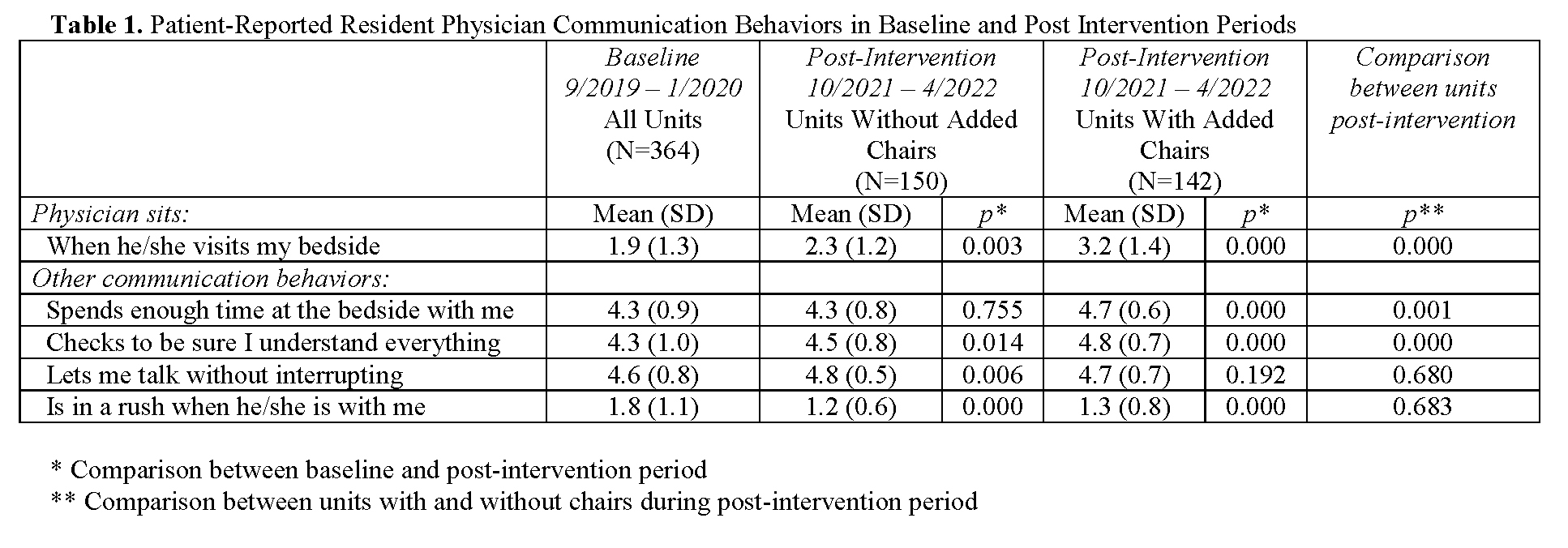

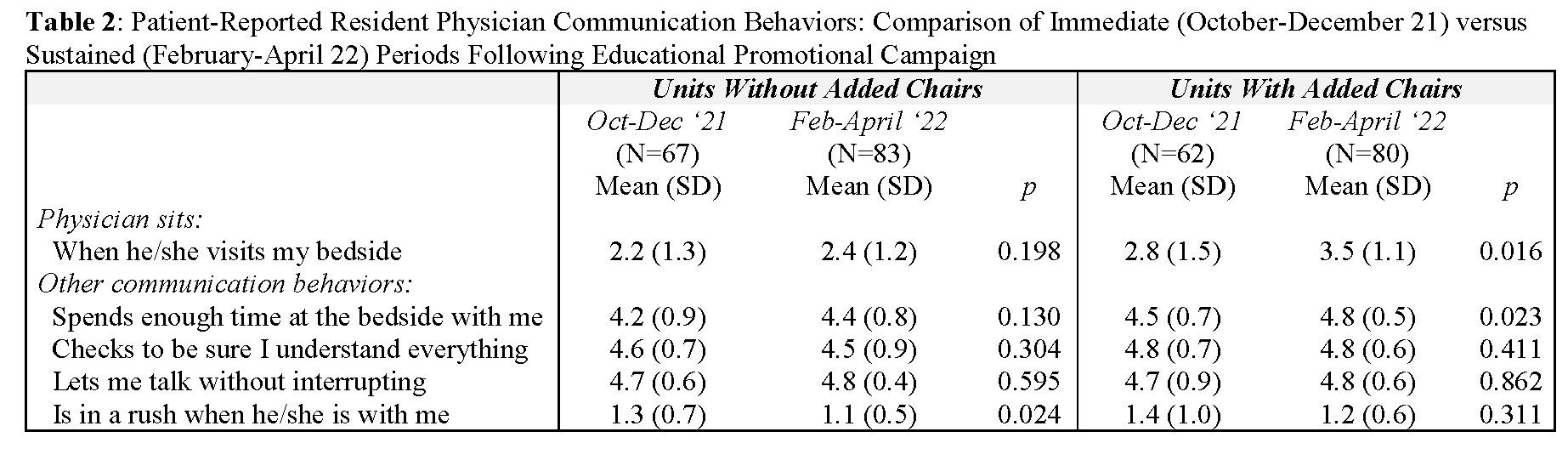

Results: A total of 256 (of 334 eligible) and 206 (of 217 eligible) patients completed surveys in the baseline and post-intervention periods, respectively, compiling a total of 364 and 292 surveys at baseline and post-intervention, respectively. At baseline across all 4 units, the mean sitting frequency was 1.9 (standard deviation 1.3). Post-intervention, this increased to 2.3 (1.2, p vs. baseline 0.003) on units without added chairs and to 3.2 (1.4, p vs baseline < 0.001) on units with added chairs. Compared to baseline, units without and units with added chairs saw improvements in other communication behaviors (Table 1). Post-intervention, compared directly to units without, units with added chairs scored higher for sitting, spending enough time at the bedside, and checking for understanding (p< 0.01 for all, Table 1) and no different for other behaviors. Similar results were observed when analyzing first-year and upper-year residents separately. Post-intervention, improvements in sitting and in other communication behaviors were sustained on both types of units throughout the 7-month survey period (Table 2).

Conclusions: Adding folding chairs to hospital rooms was associated with an improvement in patient-reported sitting at the bedside by resident physicians, beyond an improvement seen with education alone and that occurred after an 18-month pause due to the COVID pandemic. The effect of chairs was sustained throughout a 7-month period. We hypothesize that chair placement may have been effective for multiple reasons, including addressing the barrier of physicians not having a place to sit and serving as a behavioral nudge. The intervention was also associated with improvements in other patient-reported communication outcomes, providing further support that sitting may augment patient perceptions of provider communication.