Background: When people with Limited English Proficiency (LEP) access the US healthcare system, a disparity is created, leading to worse outcomes and lower quality of care.1-5 In-person interpreters are essential in circumventing these disparities, yet pitfalls to collaboration between providers and interpreters persist.6-9 This study’s goal was to assess barriers and identify opportunities for intervention at our institution when working with inpatients with LEP on the pediatric and internal medicine wards.

Methods: A mixed methodology consisting of a cross-sectional survey and thematic analysis of open-ended questions was used. Participants included residents, hospitalists, and advanced practice providers at our institution at both adult and pediatric hospitals, as well as interpreters identified on our state’s public interpreter registry. Providers and interpreters completed a 21-item (paper) and 19-item (electronic Qualtrics) survey, respectively. The primary outcome of interest was barriers to effective collaboration between interpreters and providers while working inpatient on the pediatric or internal medicine services. Descriptive statistics, t-tests, and qualitative analysis of themes were applied. Interpreters that did not have hospital experience with internal medicine or pediatrics services were excluded. The study received IRB exemption status.

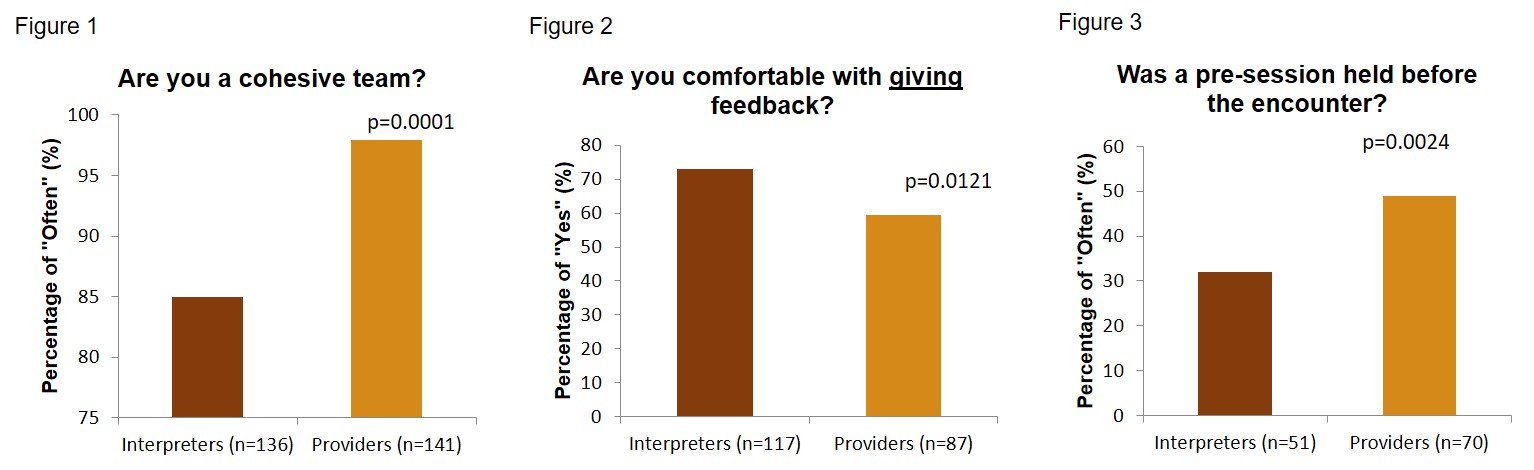

Results: 160 interpreters and 146 providers responded. As top barriers, interpreters ranked providers “talking in long sentences” (42.5%, 34.8-50.2) and “lack of punctuality” (46.2%, 38.5-54.0), whereas providers identified “not enough time” (59.7%, 51.0-68.3) and “lack of access” (54.8%, 46.1-63.6). Interpreters felt part of a cohesive team less often than providers (85.0% vs 97.9% p=0.0001). Providers remembered introducing encounters with brief summaries of the patient’s situation (pre-sessions) more often than interpreters did (49.0% vs 31.9% p=0.0024). Interpreters were more comfortable giving feedback to providers than vice versa (73.1% vs 59.6% p=0.0121). The most common themes identified as barriers on qualitative analysis were “access to interpreters” (35.2%) and “interpretation techniques” (23.2%). 87.0% of the “access” comments were concerns from providers, and 90.1% of the “techniques” comments were from interpreters regarding providers’ skills working with interpreters.

Conclusions: Limitations of the study are that findings are based on self-report, leading to recall or social desirability bias. The main strength of this study is that it uniquely and equally assessed the viewpoints of both providers and interpreters on specific behaviors when working together in the inpatient hospital setting, revealing significant discordant perceptions of team cohesiveness and communication. Other improvement topics include addressing “provider technique” and “lack of access to interpreters”, while taking into consideration the specific workflow and environment of inpatient medicine. Necessary cultural change in the area of interpreter provider collaboration on the wards requires education and reinforcement. We plan to work with our institution’s staff interpreters to implement an educational intervention for providers, especially trainees, which will address identified areas of weaknesses in 1) team cohesiveness 2) pre-session completions and 3) active feedback amongst both parties.