Background: Patients with limited English proficiency (LEP) comprise 19% of the adult population of California (1). Communication barriers between providers and patients with LEP contribute to health disparities and associate with increased adverse events (2,3). Working with professional interpreters associates with decreased hospital length-of-stay and readmission rates (4). However, few providers receive formal training on working alongside interpreters. We aimed to conduct a needs assessment of Stanford house staff on how to work most effectively with interpreters when caring for patients with LEP.

Methods: Participants were surveyed anonymously via Qualtrics regarding prior training on working with interpreters and their experience caring for patients with LEP. Our survey was distributed to internal medicine residents by email. Incoming house staff who passed by the Interpretation and Translation Services table at Stanford GME orientation were also invited to participate. To identify best practices in interpretation, we collaborated with the Department of Interpretation and Translation Services and also referenced a validated rubric for assessing medical student skills in working with interpreters (5).

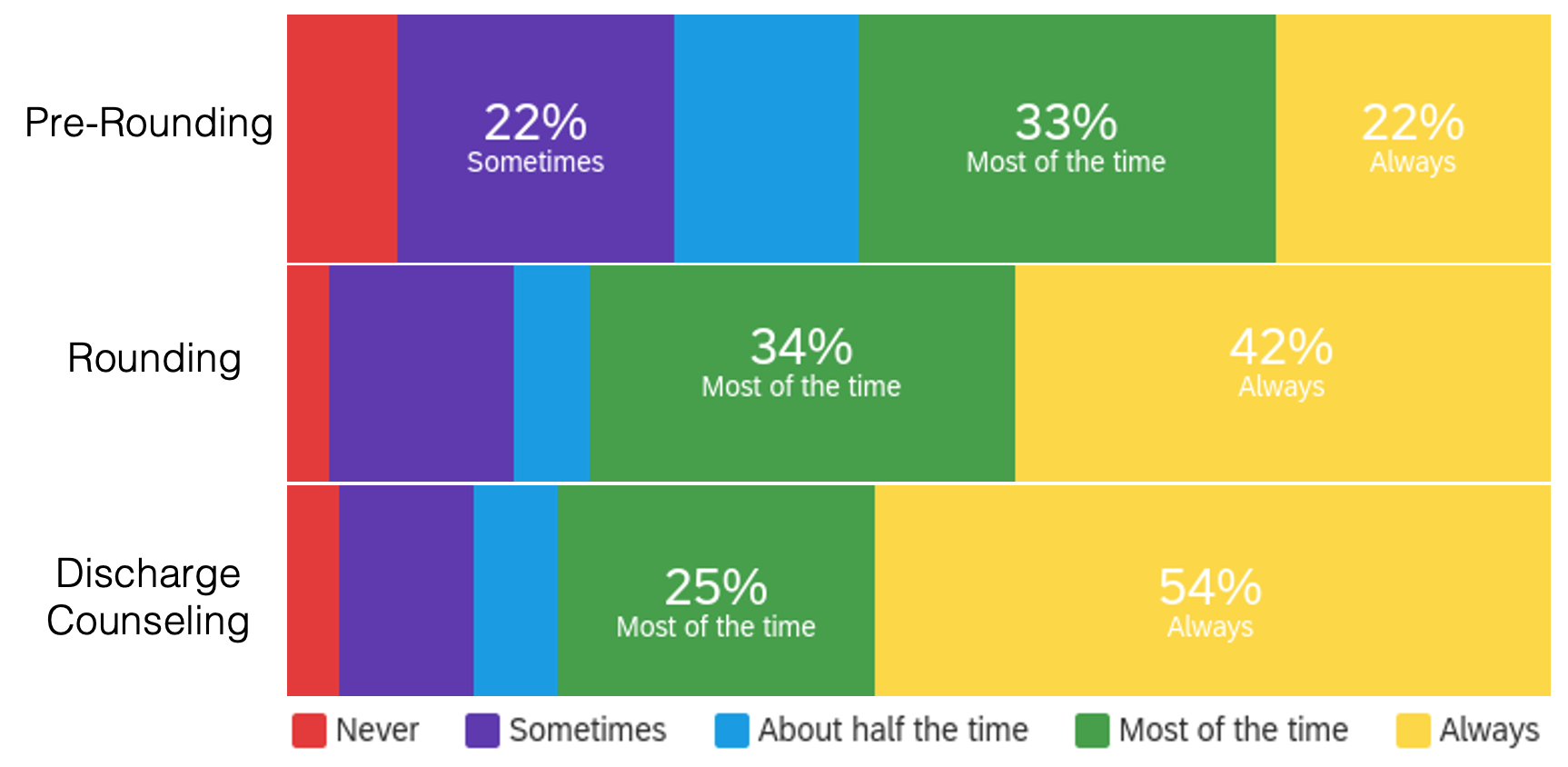

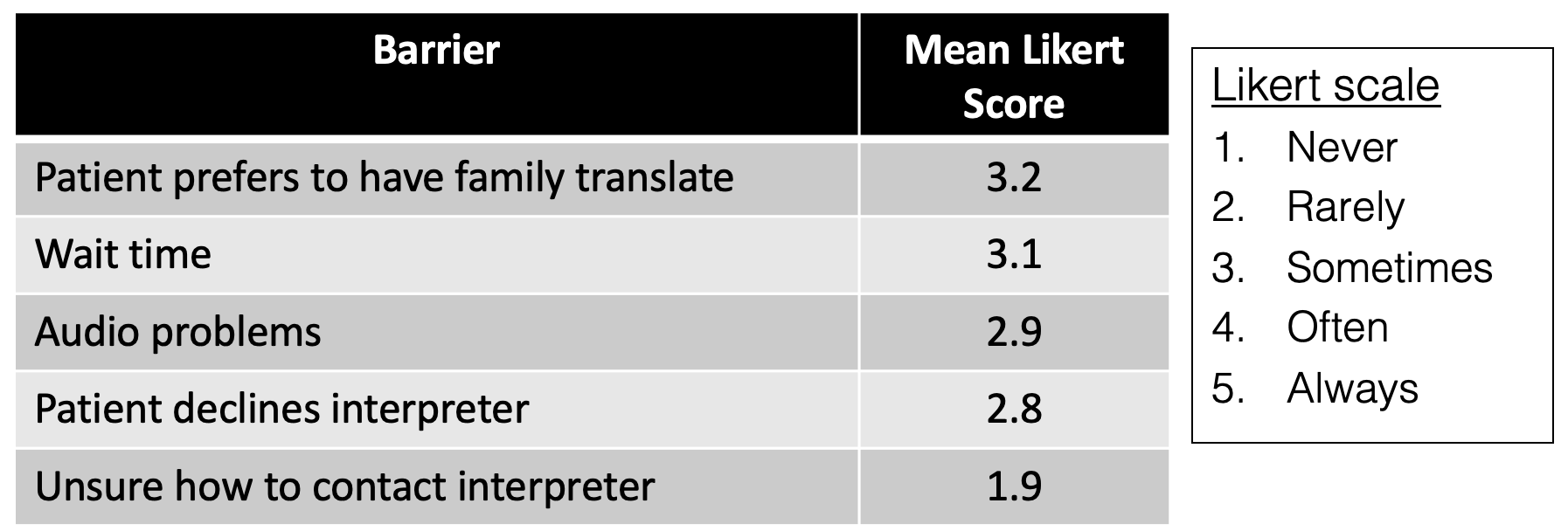

Results: Our survey had 149 respondents (42% PGY1, 14% PGY2, 12% PGY3, and 32% PGY4+). The most represented specialties were internal medicine or medicine subspecialty (48%), surgery or surgical subspecialty (15%), and pediatrics (9%). 42% reported fluency in a language other than English. When asked about prior training on working with interpreters, 57% reported training in medical school but 19% of respondents had no prior training. Among PGY2+ respondents, only 33% had received training on this topic at some point during residency.Percent of respondents who always accessed a professional interpreter when caring for a patient with LEP was 22% for pre-rounding, 42% for rounding, and 54% for discharge counseling (Figure 1). The most common barrier to including an interpreter was the patient preferring to have a family member assist with communication, followed by wait times (Table 1). When surveyed about alternate methods of communication, 72% of respondents had used patient’s family member, 50% had used other staff members, 42% had spoken English, and 61% had used their own non-English language skills.

Conclusions: Despite caring for a large population of patients with LEP at our institution, only a third of graduate medical learners were exposed to language equity training during residency. Residents inconsistently involved professional interpreters and frequently reported using alternate means of communicating with patients with LEP, including ad hoc interpreters, English, or their own non-certified foreign language skills. This may facilitate miscommunication and increase adverse events. Formal education on language equity is needed during residency and fellowship.