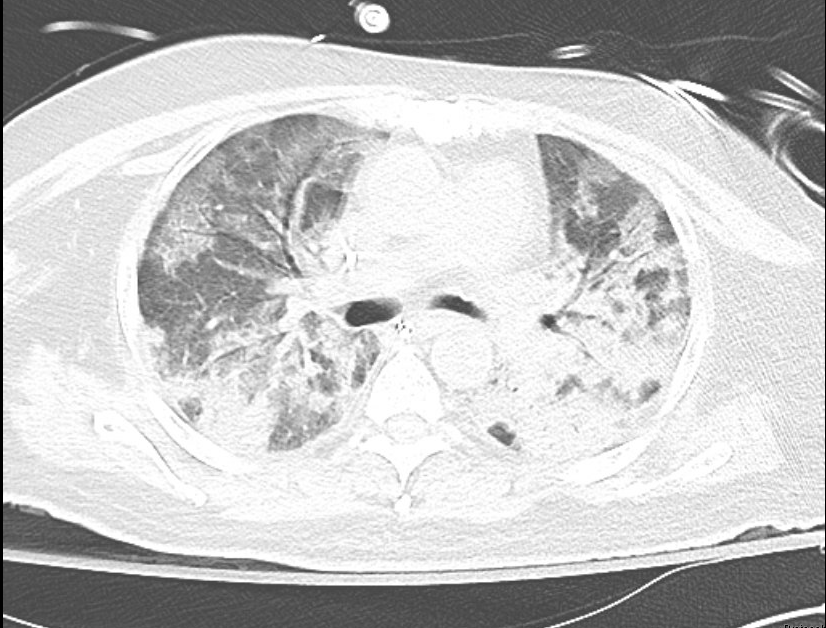

Case Presentation: A 63-year-old man with significant history of deceased donor transplant (18 months prior to presentation), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, who presented with two weeks of fevers and malaise. His other symptoms included drenching night sweats, shortness of breath, and diffuse pleuritic chest pain, however he denied cough. A recent exposure was a renovation of a room with water damage and mold.His transplant history was notable for basiliximab induction complicated by donor and recipient low-level cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia, pancytopenia, and tacrolimus toxicity, but these were resolved prior to his admission. He completed 6 months of post-transplant atovaquone for PJP prophylaxis. For the past year, his kidney function has been stable but suboptimal with CKD stage IV and nephrotic range proteinuria. His medications have remained unchanged: monthly belatacept infusions, mycophenolate mofetil 500mg twice a day, and prednisone 5mg daily. His admission labs were notable for a white blood cell count of 3.7x 10^3/uL and creatinine of 2.43 mg/dl (baseline). Chest computed tomography revealed mixed airspace-interstitial infiltrates with diffuse ground-glass opacities and bronchiectasis (Fig. 1). He was started on empiric coverage of bacterial vs. fungal pneumonia with vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, azithromycin, and voriconazole. Because of his persistent hypoxemia, a bronchoscopy was performed and returned positive for Pneumocystis pneumonia (PJP). He was started on sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim and steroids by hospital day 4.Unfortunately, his hypoxia worsened and he required intubation for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). There were empiric trials of micafungin, meropenem, acyclovir, doxycycline, primaquine, and clindamycin. A repeat bronchoscopy was unrevealing and his ARDS worsened. After 3 weeks of intubation without clinical improvement, the family declined tracheostomy and the patient was palliatively extubated and expired.

Discussion: PJP is a morbid infection predominantly associated with AIDS, hematologic malignancies, chronic high dose steroids or immunosuppressive medications, and transplant (hematopoietic cell and solid organ). In solid organ transplantations (SOT), the risk of PJP is highest in the first 6 months after transplantation.[1] However, PJP outside of the 6-month window is being increasingly recognized and has been associated with CMV viremia, lymphopenia, and immunosuppressive treatment failures[2,3] – all present in our patient.

Conclusions: There are no clear guidelines for life-long PJP prophylaxis in renal transplant recipients, but various professional societies recommend anywhere between 4 to 12 months.[4] Emerging data will need to both shape recommendations for extending prophylaxis in risk-stratified SOT recipients and raise the index of suspicion for prompt PJP treatment.