Background: Alcohol withdrawal is a common issue in hospitalized patients and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Alcohol withdrawal occurs when the gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) stimulating effect of alcohol is removed, resulting in an excess of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate. Treatment typically consists of as needed benzodiazepines, which activate GABA. However, this reactive approach can be ineffective, particularly in high-risk patients. Phenobarbital is an alternative treatment option. Phenobarbital has a long half-life and is able to activate GABA and inhibit glutamate. Concerns regarding safety have limited its use, along with a paucity of data supporting its efficacy. In this study we compare the outcomes of a cohort of patients with alcohol withdrawal treated with fixed dose phenobarbital to a historical cohort of patients treated with as needed benzodiazepines.

Methods: We introduced a fixed dose phenobarbital protocol at our institution to treat patients with alcohol withdrawal on acute care general internal medicine in December 2021. In this study, we compared patients admitted to the hospital from January 1 to June 30, 2018 and treated for alcohol withdrawal using as needed benzodiazepines to all patients admitted to the hospital from January 1 to June 30, 2022 and treated for alcohol withdrawal utilizing the phenobarbital pathway. Our primary endpoint was a composite of death or ICU transfer. Secondary outcomes included seizure, delirium, use of antipsychotics, oversedation, length of stay, patient disposition, 30 day readmission and 30 day re-evaluation in the emergency department.

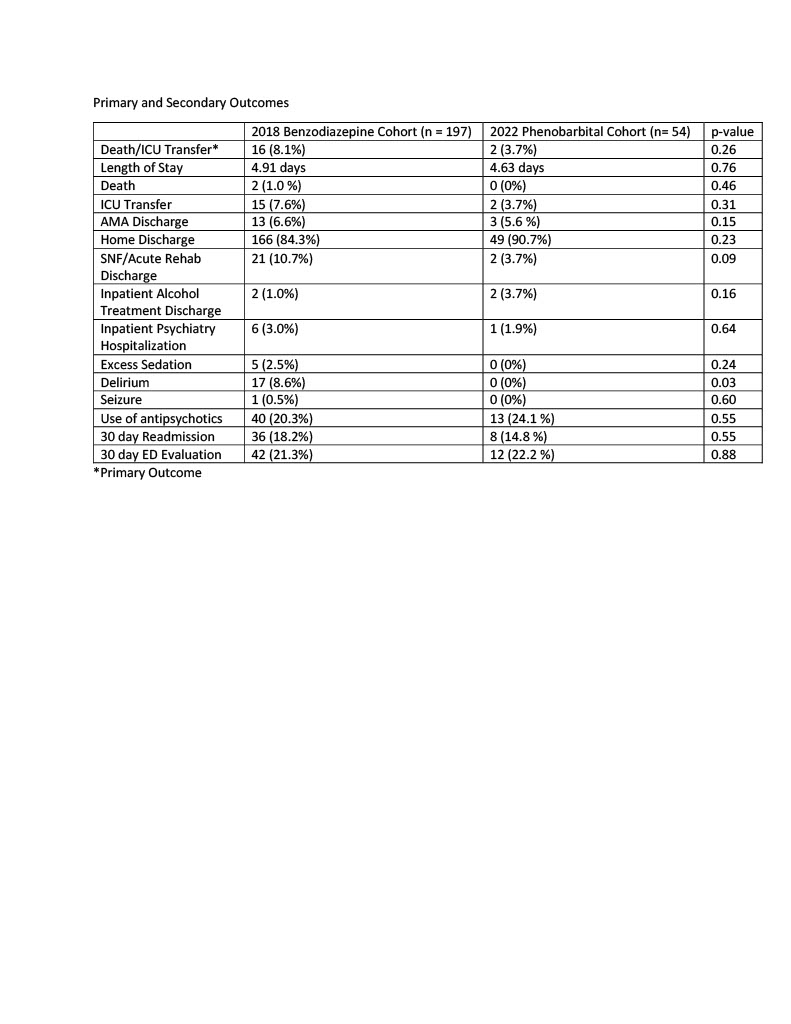

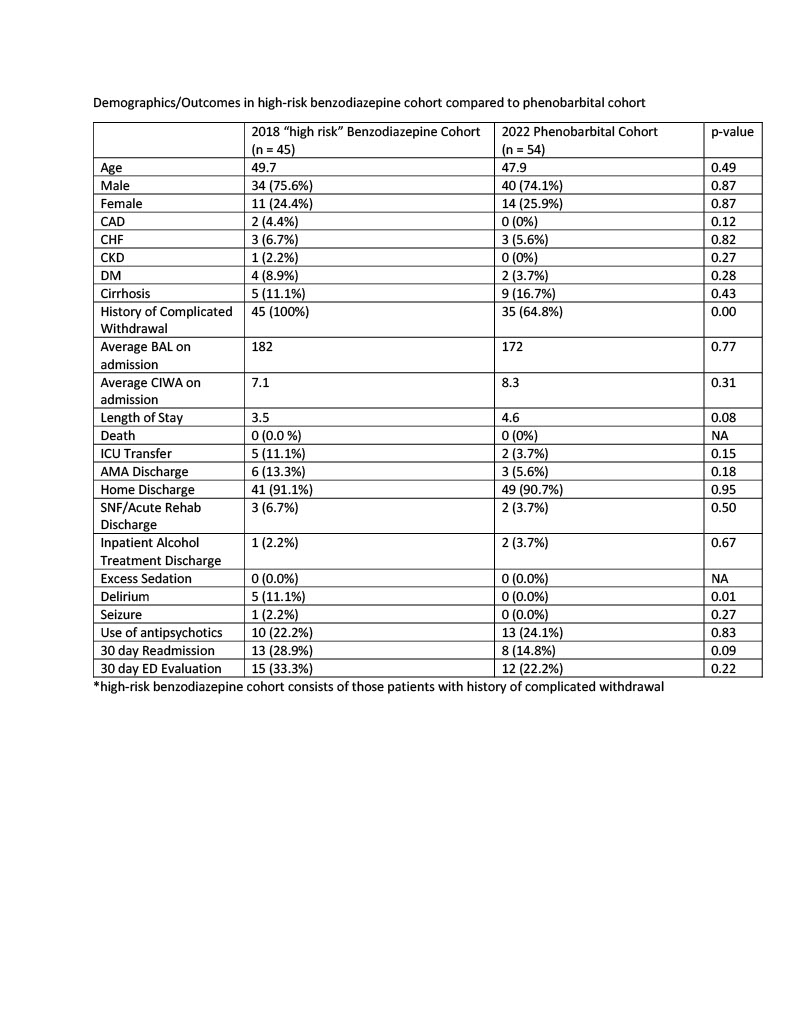

Results: Between January 1 and June 30, 2018, 197 unique patients were admitted to the hospital and treated for alcohol withdrawal with as needed benzodiazepines. From January 1 to June 30, 2022, 54 unique patients were admitted and treated for alcohol withdrawal with phenobarbital. The benzodiazepine cohort was older (53.4 vs. 47.9) and a greater proportion had diabetes (12.7 vs. 3.7%), heart disease (9.6 vs. 5.6%), and kidney disease (5.6 vs. 0.0%). The primary outcome occurred more frequently in the benzodiazepine cohort (8.1% vs. 3.7%) but did not reach statistical significance (p-value 0.26). The phenobarbital group had a lower frequency of oversedation (0 vs. 2.5%), delirium (0 vs. 8.6%), seizure (0 vs. 0.5%), and 30 day readmission (14.8 vs. 18.2%) but results only reached statistical significance with regards to delirium (p-value 0.03). In a sensitivity analysis, patients in the benzodiazepine cohort who were considered “high risk” due to a prior history of complicated withdrawal were compared to the phenobarbital cohort. This created cohorts with very similar baseline characteristics. The phenobarbital group had lower rates of ICU transfers, seizures, delirium, and readmissions but results only reached statistical significance with regards to delirium.

Conclusions: In this study, we compared fixed dose phenobarbital to as needed benzodiazepines for treatment of alcohol withdrawal on an acute care medical service. Phenobarbital appeared to be a safe and effective treatment. We found lower rates of ICU transfer, death, seizure, oversedation, delirium, and 30 day readmission when phenobarbital was used, although results only reached statistical significance with regards to delirium. Larger, randomized studies are needed to better understand if phenobarbital should be used preferentially in specific patient populations presenting with alcohol withdrawal.