Background: Discharge checklists may reduce medical errors. Traditional paper checklists do not fit into the current workflow in centers that utilize electronic medical records (EMRs). In an era where team-based care is becoming widespread, defining each person’s role in discharge practices is increasingly important.

Methods: Our aim was to develop and implement a standardized discharge checklist into our university hospital’s EMR that was tailored towards internal medicine housestaff. We sought to analyze utilization of the checklist and compare the effects of its usage on discharge best practice items. As this was a pilot study we also sought out qualitative feedback on the project from participating medicine housestaff.

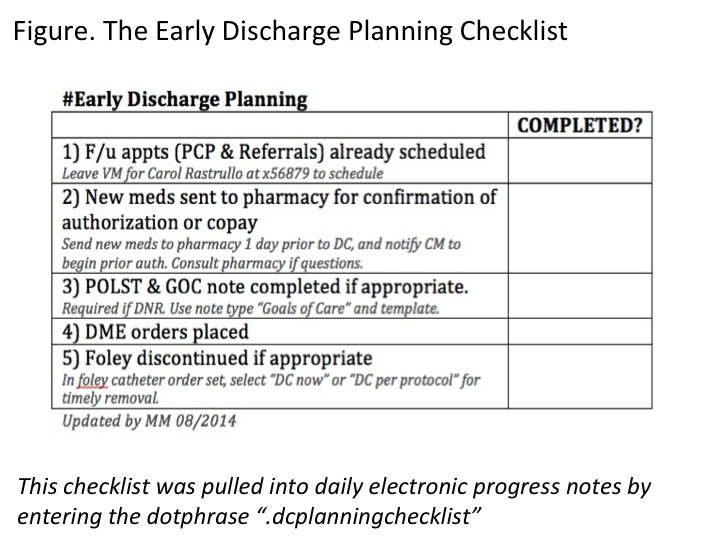

Using focus groups and published best practices, we selected 5 tasks necessary for safe discharges to include in our checklist: follow-up appointments, medication education, Physician Order for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form completion, discharge equipment orders, and timely catheter discontinuation. We created a “dotphrase” in our EMR that could pull the checklist into daily physician progress notes (Figure). We randomized each of 5 general medicine ward teams to receive either weekly reminders to use the checklist dotphrase in their daily notes (intervention team) or less frequent reminders to use any existing methods they already had to remember discharge tasks (control team). Over a 5-week period, we collected data on checklist usage, as well as outcomes relating to the checklist tasks across all general medicine teams.

Results: The intervention group had 269 (60%) patient encounters and the control group had 179 (40%) encounters during the pilot period. Checklist usage in the intervention group was at 23% (ie, 61 encounters contained the checklist in at least one note entered during the encounter). Patients in both groups were of similar case mix index (p=0.85). Housestaff in the intervention group were more likely to consult discharge pharmacists for medication education than those in the control group (30% vs 14% of encounters; p<0.001). There were no significant differences in length of stay, follow-up appointment scheduling, or POLST completion in either group.

Overall, housestaff in the intervention group liked seeing and updating the discharge checklist in their daily notes. They wanted more instruction on how to actually complete the discharge tasks. They also wanted to see discharge task reminders earlier in the work day.

Conclusions: An EMR based discharge checklist can improve completion of some best practice items such as consulting a discharge pharmacist. Medicine housestaff are willing to use an EMR-based checklist to aid in discharge tasks. There are opportunities to improve actual usage of the checklist and to better tailor it to medicine housestaff workflow.