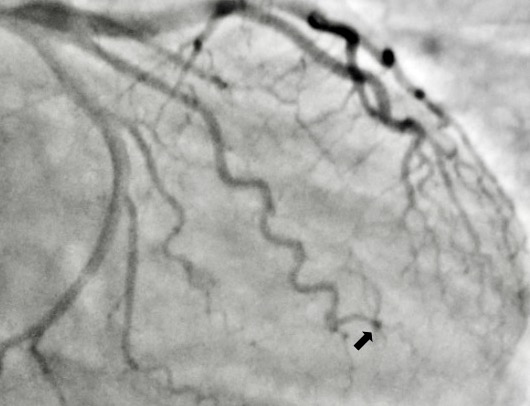

Case Presentation: A 22-year-old woman, gravida 1, para 1, with an unremarkable medical history, presented with sharp left-sided chest pain radiating to the left arm, two weeks postpartum. Initial evaluation revealed stable vital signs, T wave inversions on lateral leads in the EKG, and elevated troponin levels (23.271 and 23.173). Coronary catheterization exposed near 100% occlusion in the lateral OM1 branch, indicating spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). Despite the vessel’s size and location, a decision for medical management over invasive intervention was made. The patient responded well to conservative measures, experiencing resolution of chest pain. Subsequent plans for aggressive medical therapy were adjusted due to her breastfeeding status and absence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Beta blockers and statins were not given due to her breast feeding status and absence of cardiovascular risk factors. At discharge, she remained stable and asymptomatic, with a subsequent uneventful 4-week follow-up, indicating a favorable response to the chosen approach.

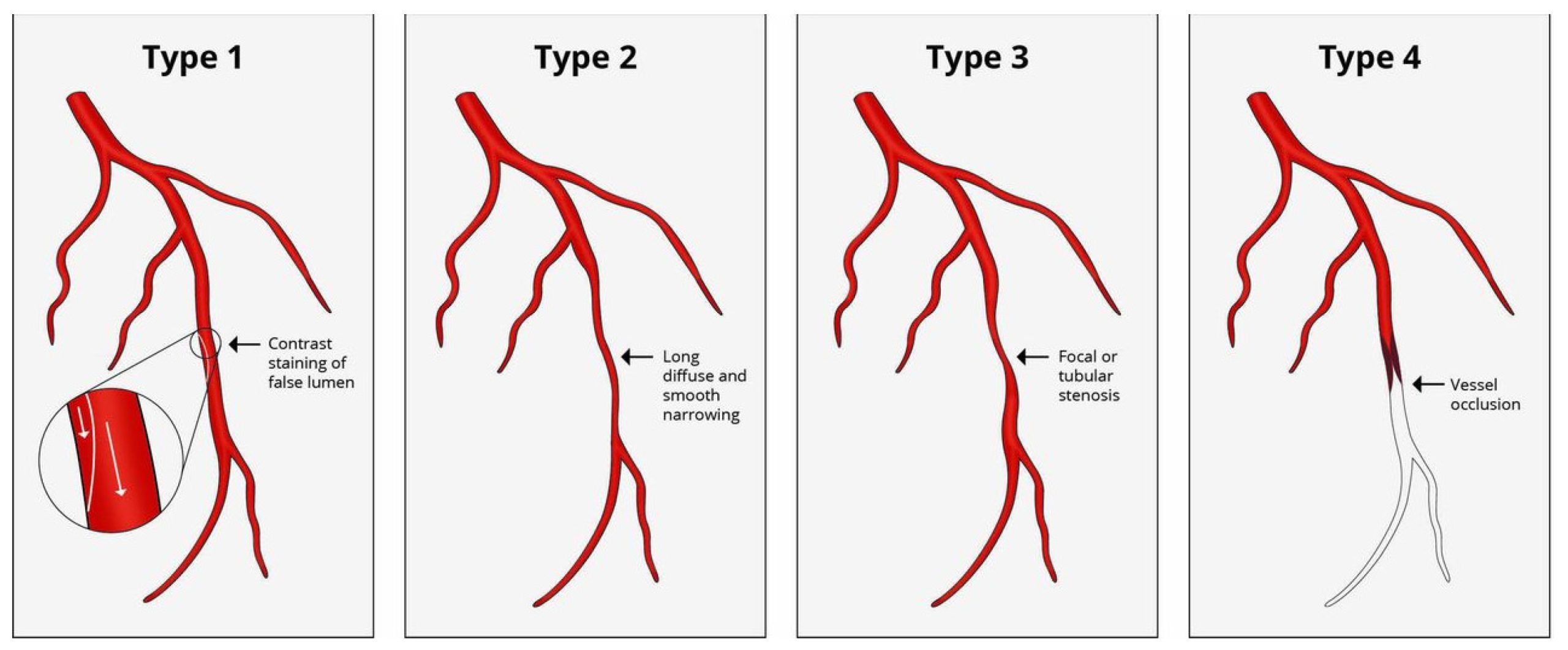

Discussion: Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is an unpredictable, non-traumatic, and non-iatrogenic event, predominantly affecting women more than men. Pregnancy-associated SCAD (P-SCAD) comprising up to 17% of cases in women. The condition involves intramural hematoma formation, leading to intima separation and compression of the true lumen, causing artery obstruction without the typical association with plaque disruption seen in atherosclerosis-related events.Angiographic classification (Saw Classification) distinguishes four types of SCAD, with Type 2 being the most common. Different theories propose the origin of SCAD, involving either an intimal tear (inside-out theory) or spontaneous hemorrhage from vasa vasorum (outside-in theory). Both pathways lead to hematoma formation, intimal tear, true lumen compression, and subsequent ischemia.Management of SCAD, particularly in the unique context of P-SCAD, necessitates tailored approaches. Traditional ischemia treatments may not directly apply, and the use of beta-blockers, anti-platelet therapy, and statins is debated due to the absence of atherosclerosis in SCAD. Beta-blockers show promise in reducing recurrent SCAD risk, and anti-platelet therapy is considered for up to 12 months in non-PCI patients. Statin use remains controversial, highlighting the need for individualized patient-specific considerations, including pregnancy, breastfeeding, and potential contraindications.

Conclusions: Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for SCAD in young females presenting with chest pain during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Early recognition and intervention contribute to improved outcomes and reduced complications. Following confirmation via angiogram, conservative management with pharmacologic measures should be individualized based on risk stratification. Further considerations must include the safety and efficacy of interventions, particularly in breastfeeding patients.