Background: Unnecessary inpatient laboratory testing is common and negatively impacts patients by causing discomfort and iatrogenic anemia. Such testing also burdens a busy phlebotomy team, particularly when patients decline labs due to recency of previous checks. Audit and feedback interventions are known to reduce low value practices in medical residents, but no published study has evaluated the impact of peer-defined standards used to provide comparative feedback on resident practices. Furthermore, no published data has measured the impact of such an intervention on phlebotomist workflow.

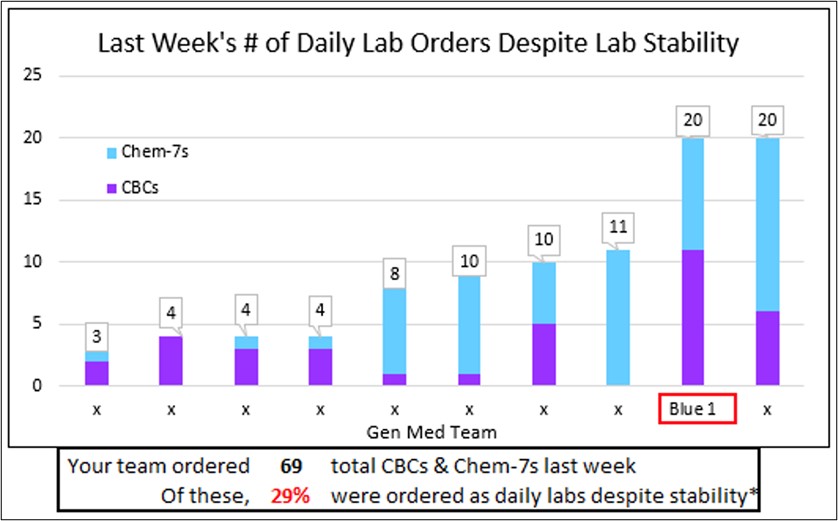

Methods: We surveyed internal medicine residents using a modified Delphi technique to establish thresholds for “stable” complete blood count (CBC) and chemistry panels, such that an additional daily lab check would be unnecessary in the absence of clinical changes. We then compared 32 weeks of pre-intervention data to resident lab ordering practices on general medicine patients for 21 weeks during the intervention and 17 weeks post-intervention. During the intervention period, we provided weekly feedback to resident teams on their frequency of daily lab testing despite preceding stable labs, compared to the other resident teams (Figure 1). The primary outcome was total number of CBCs ordered by residents, measured as labs per patient-day to adjust for fluctuations in team census. Other measures included labs ordered despite stability (LODS), and the total number of number of “patient-declined laboratory draws” per month to track an additional possible impact on phlebotomist workflow. Data were analyzed using t-tests and statistical process control charts.

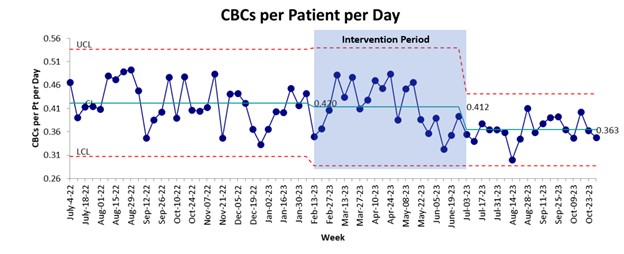

Results: The post-intervention period saw a significantly lower number of CBCs despite stability per patient-day (LODS) (0.0679 pre vs 0.0481 post, p<.001) and total CBCs per patient-day (0.420 pre vs 0.363 post, p<.001) (Figure 2). This approximates 25 CBCs avoided per week on an average daily census of 64 medicine inpatients. Chemistry panel ordering was similar before and after the intervention. The mean number of patient-declined laboratory draws was 89 per month in the 7 months pre-intervention and 43 per month in the 6 months during the intervention (p<.001). No difference was detected in the number of rapid response or code blue alerts following the intervention.

Conclusions: This audit and feedback intervention using laboratory stability criteria established by medical residents safely led to a sustained reduction in the number of CBCs ordered by residents. No difference in chemistry panel ordering was detected, potentially due to the need for close monitoring of electrolytes and renal function in many hospitalized patients for reasons unrelated to lab stability, such as use of intravenous antibiotics or fluids. Notably, patient-declined labs decreased after starting the intervention, a metric important to the phlebotomy group at our institution due to the workflow disruption caused by declined labs.