Background: Antibiotics prescribed at hospital discharge account for over half of antibiotic exposure related to hospitalization and contribute to antibiotic-related harm. We hypothesized that an antibiotic timeout to reconsider antibiotic necessity, selection, and duration prior to discharge could reduce antibiotic overuse. Thus, we conducted a 6 month prospective, controlled pilot study to determine feasibility and acceptability of an antibiotic timeout at discharge.

Methods: Between 5/1/2019 and 10/31/2019, we conducted a prospective, non-randomized pilot of a pharmacist-facilitated antibiotic timeout prior to discharge. Both clinical pharmacists and hospitalists received education and a pocket card which outlined institutional guidelines for appropriate antibiotic selection and duration. Patients on the hospital medicine service who were anticipated to be discharged on oral antibiotics and did not meet exclusion criteria (e.g. complicated infection) were eligible for a 4-question antibiotic timeout. The timeout focused on discontinuing unnecessary antibiotics, narrowing broad-spectrum antibiotics, reducing duration, and improving documentation. To facilitate communication, the timeout occurred in person between clinical pharmacists and hospitalists during rounds. In the event of a patient being discharged on antibiotics, the pharmacist was notified via pager and contacted the hospitalist to perform a timeout if not completed previously. Patients on general medicine (resident covered) services who had similar infections served as the control group. Mixed-methods (observations, interviews, surveys) were used to determine our primary outcome of feasibility. Logistic regression was used to look at secondary outcomes of slope/level change post-intervention in adjusted rates of antibiotic use at discharge compared to the control group.

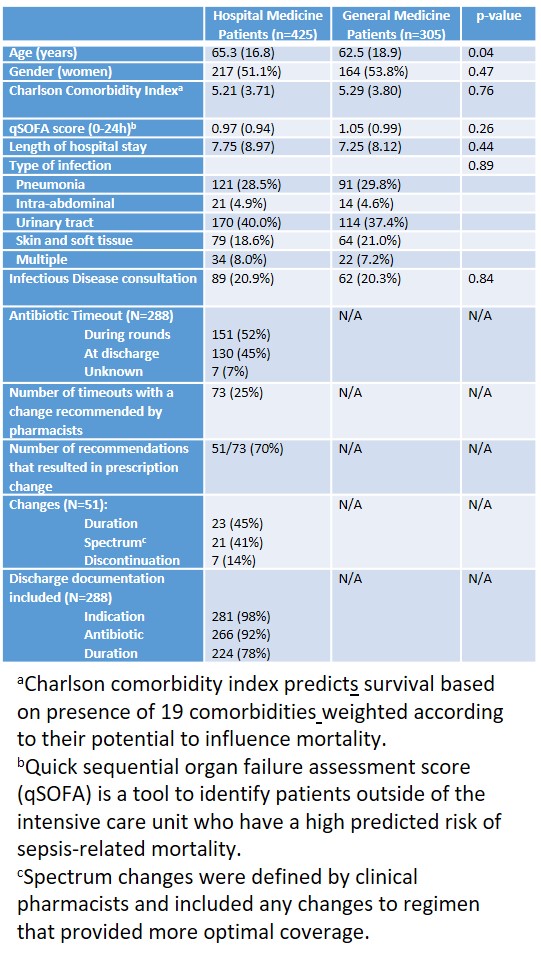

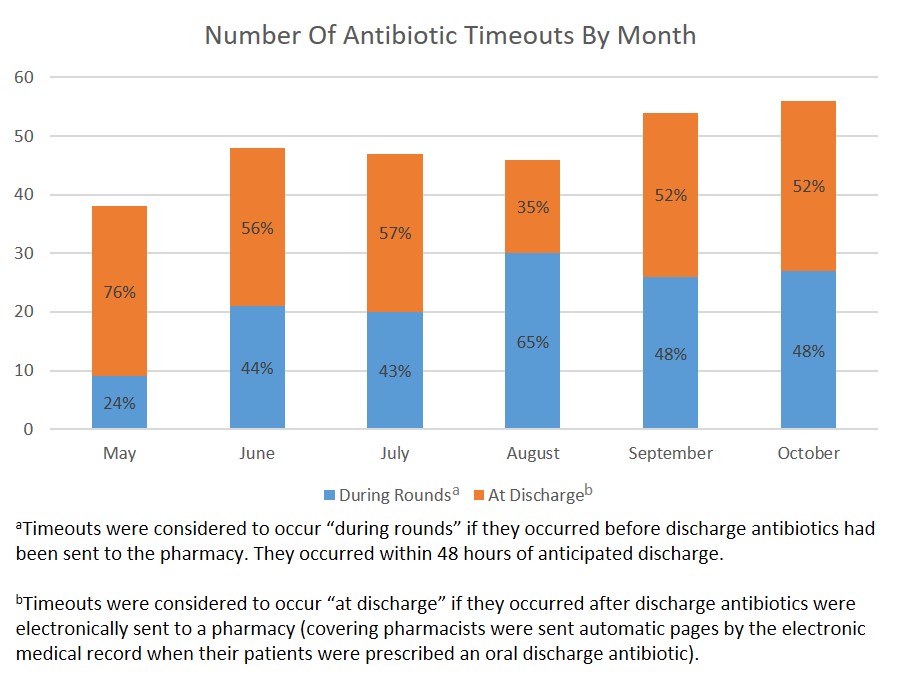

Results: Antibiotic data were available on 425 patients and timeout data were available on 288 patients discharged from the hospital medicine service (Table 1). The majority (52%) of timeouts occurred during rounds (Figure 1) with changes made in 51 (18%) patients. The median time to complete a timeout was 5 minutes per pharmacist and 2 minutes per hospitalist. Eighty-five percent of hospitalists agreed/strongly agreed the intervention was useful. Qualitative feedback from pharmacists led us to simplify exclusion criteria. We also found that, due to the perceived value of this intervention, pharmacists often conducted timeouts in the control group. Adjusted rates of antibiotic prescribing at discharge decreased post-intervention, but were not significantly different when compared to changes in prescribing over time in the control group. In the timeout group, antibiotic duration was appropriately documented in 77% of discharge summaries (improved from 57% in 2018; P<0.001).

Conclusions: This pilot study demonstrated an antibiotic timeout prior to discharge is feasible, acceptable, and changed prescribing in 18% of patients. Intervention feasibility improved after simplifying exclusion criteria. The high acceptability of the intervention may have led to substantial contamination, limiting the ability of our pilot to demonstrate an effect on prescribing compared to controls. Next steps include expanding the intervention to other services and evaluating the intervention’s effect on antibiotic overuse at discharge.