Background: The phrase “Second Victim” describes the psychological/emotional trauma healthcare providers experience after being involved in a near-miss, minor or serious medical error, or unanticipated adverse patient outcome. Affected providers report feelings of guilt, anger, and loss of confidence, with little support from their institutions. Second Victim Programs (SVPs) were introduced to improve support for providers, yet little is known about their availability and structure. We sought to: (a) establish the prevalence of SVPs across the top 20 US News and World Report (USNWR) healthcare institutions; and (b) compare and contrast their structure and outcomes.

Methods: The 2017 top 20 Honor Roll Hospitals were identified on the USNWR website. To obtain a contact, we searched for phrases such as “Second Victim”, “Safety”, “Quality”, and “Risk” on institution websites or contacted the hospital operator to identify relevant individuals. Once identified, individuals agreed to recorded phone interviews, which were transcribed and independently reviewed by 2 authors. A text-based analysis of transcriptions was performed, identifying quantitative information and qualitative themes that unified or distinguished programs, including information on participation, accessibility, content, determinants of success and challenges.

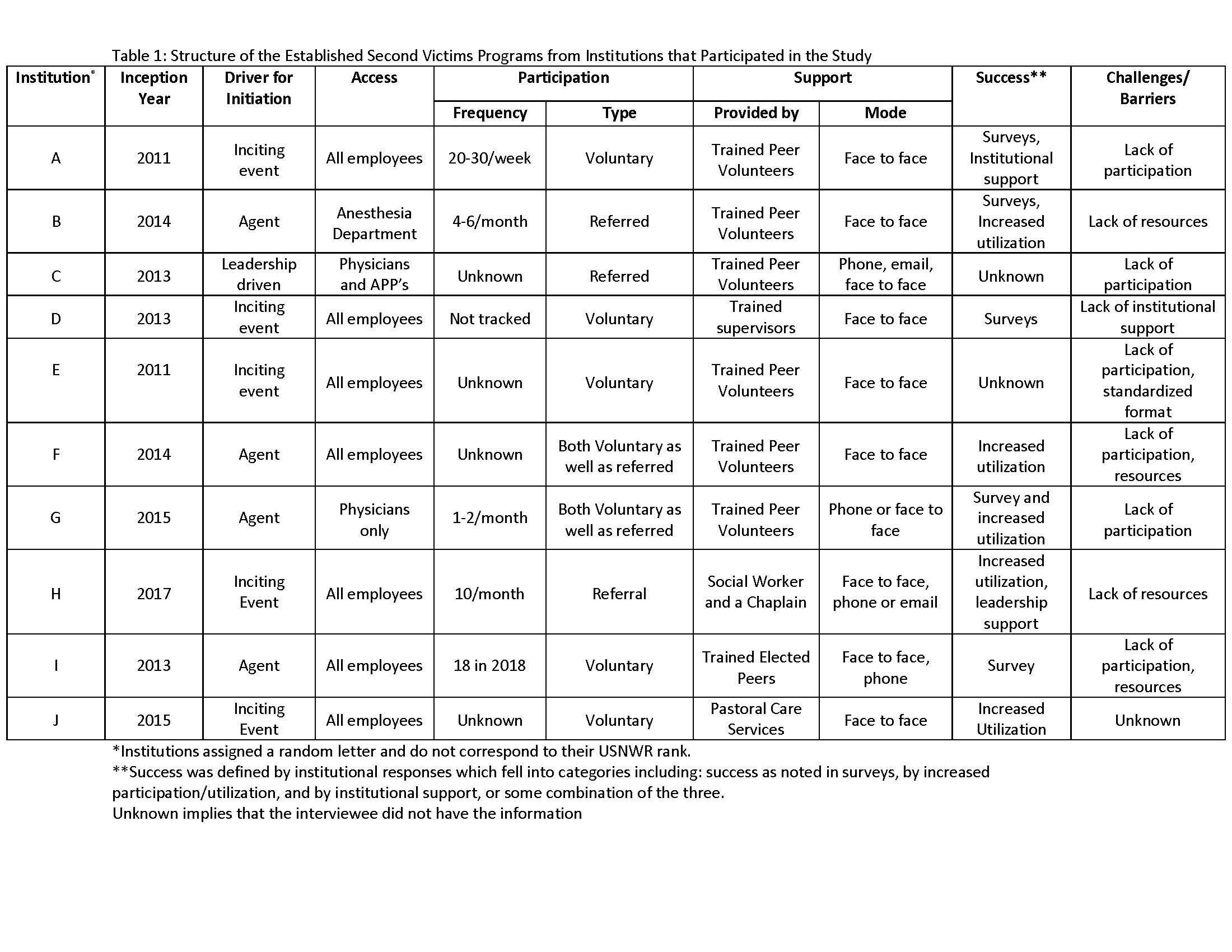

Results: Of the 20 hospitals, 4 had information regarding SVPs on their website and 8 were discovered via phone calls to the institution. Twelve institutions elected to participate (response rate of 71%). Ten of the 12 institutions had dedicated SVPs that were started between 2011-2016. Drivers for initiation were adverse events involving staff (n=5) or provider recognition of need (n=4). Access to SVPs varied: 7 were available to all employees; 1 to physicians only; 1 to physicians and APPs only, and 1 was exclusive to anesthesia department. Six SVP’s tracked data regarding utilization and reported a range of 1-30 individual users per week. Physicians represented 10%-80% of all users of SVPs for employees. Participants either sought support voluntarily (n=5); or were referred to the program (n=3), or both (n=2). Support was provided by trained peer volunteers, such as RN and physicians (n=6); trained managers (n=1) or individuals elected by peers to provide support (n=1). In two SVPs, social workers and clergy provided support. Face to face support was provided by all SVPs. Success was measured by: surveys (n=5) (including culture of safety surveys); metrics suggesting growing utilization (n=5), and by institutional support (n=2). Barriers to sustainability of SVPs included lack of: institutional buy-in (n=1); a standardized support format (n=2); resources (n=4); and participation (n=6). As a result of SVPs, 2 institutions made hospital wide systematic changes, while another made departmental changes.

Conclusions: Most USNWR Honor Roll hospitals that participated have SVPs. However, variation in structure, performance, and measures of success were observed. How best to define success appeared to be a challenge for these programs, often limiting participation and resource allocation. Further research to understand how to eliminate barriers to SVP’s and develop structures that link to individual and institutional success appear necessary.