Case Presentation: A 14yo girl presented with syncope and 4 days of URI symptoms. She had no past medical or family history.

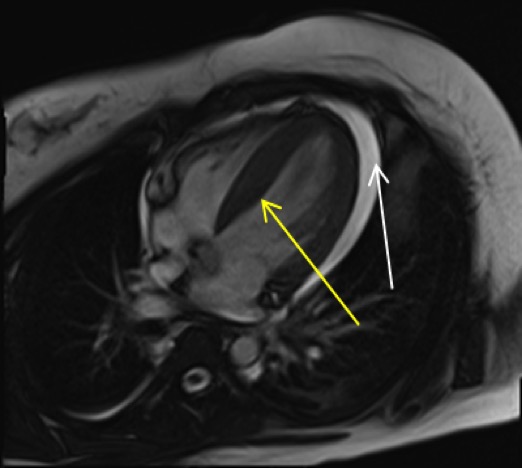

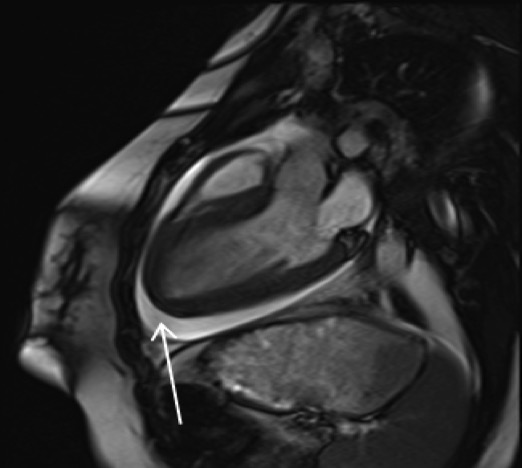

On presentation, she was hypotensive with mildly elevated lactate, troponin, and BNP, and an unremarkable ECG and chest radiograph. Initial echocardiogram showed normal LV function. Cardiac MRI revealed a pericardial effusion and increased myocardial wall enhancement. Infectious and rheumatologic workup was notable only for Parainfluenza 1 on nasal swab.

Over the next 24 hours her condition significantly worsened. She developed multi-organ failure including cardiogenic shock, transaminitis, renal insufficiency, and altered mental status requiring intubation and vasopressors. There was a rapid increase in pericardial fluid causing tamponade and she underwent an emergent pericardial window procedure. She was subsequently placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for rapid deterioration in cardiac function with an ejection fraction of 15% despite optimal inotropic support.

Over the next week, she showed significant improvement and was successfully decannulated. Inotropes were weaned with the addition of carvedilol and lisinopril. At discharge 3.5 weeks after admission, her cardiac function had normalized.

At follow up 2 months after discharge, the patient’s echocardiogram was essentially normal and her carvedilol and lisinopril were discontinued. She continues to do well 12 months out with normal cardiac function off all medications.

Discussion: Myocarditis is a sequela of certain viral infections. It is relatively rare among children and there is a range of presentations from self-limited to fatal. Fulminant myocarditis is characterized by rapid deterioration and hemodynamic collapse.

Human parainfluenza I (HPIV-1) is a virus that usually causes mild upper respiratory tract infections. There are case reports of parainfluenza 2 and 3 causing fulminant myocarditis, but there are no cases of fulminant myocarditis secondary to parainfluenza 1.

Endomyocardial biopsy had previously been the diagnostic standard. However, tracheal aspirate PCRs are highly correlated with myocardial PCRs and are safer, making this the typical method of diagnosis now.

Many cases are treated symptomatically while some require inotropic and vasopressor support. Ventricular assist devices or ECMO may also be required. Fulminant myocarditis can lead to long-term morbidity, but of those that do survive, many recover normal heart function. IVIG and steroids are sometimes used, though they are not typically recommended.

We present a case of fulminant viral myocarditis in a patient with a viral prodrome and HPIV-1. Previous work has suggested high correlation with nasal or tracheal swabs and tissue samples, so we can reasonably attribute this case to HPIV-1. Our patient ultimately did well with normalization of cardiac function.

Conclusions: Fulminant myocarditis is a rare, rapidly progressive and frequently fatal disease with unclear diagnostic criteria and treatment modalities. As we describe, it can be diagnosed in the setting of rapidly progressive heart failure and positive PCR test for viral infection. Originally, enteroviruses were believed to be the main cause of viral myocarditis, but this case adds to the growing list of respiratory viruses associated with viral myocarditis. The main treatment should be supportive care without steroids or IVIG and ECMO when less invasive interventions fail.