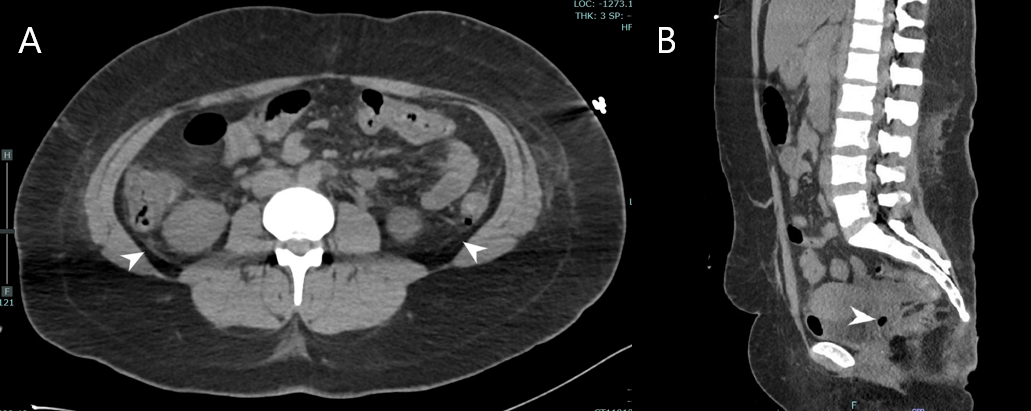

Case Presentation: Patient was a 26-year-old female with history of methamphetamine abuse, previous C trachomatis infection, and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who presented via EMS for acute hypoxic respiratory failure and unresponsiveness and was intubated in ED. Initial vitals include systolic blood pressure of 80, undetectable diastolic blood pressure, heart rate of 168 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 31 breaths per minute, temperature of 40.9 °C, and oxygen saturation of 96% on the ventilator. Exam was significant for sinus tachycardia, lungs clear to auscultation, soft abdomen, and petechiae on bilateral upper extremities. Lab abnormalities included creatinine of 2.35 mg/dL, bicarbonate of 13 mmol/L, AST 65 U/L, and ALT 78 U/L. Toxicology screen was positive for methamphetamine. IV norepinephrine, meropenem, and vancomycin were initiated. On day two of admission, the patient developed DIC with mucosal bleeding, decreased platelets, decreased fibrinogen, elevated INR, and elevated D-Dimer. Blood, urine, and respiratory cultures grew no organisms. On day four of admission, nursing staff noticed foul-smelling, purulent vaginal discharge. CT of the abdomen-pelvis found intra-abdominal free fluid and intrauterine free air (Figure 1).Vaginal wet preparation microscopy revealed T vaginalis. Lab testing for C trachomatis, N Gonorrhoeae, and M Genitalium were negative. Rapid plasma reagin and HIV testing were negative. Antibiotics were adjusted to doxycycline, metronidazole, and cefepime. The patient’s hemodynamic instability improved and her DIC resolved. She was extubated on day 7 of hospital admission and discharged without further complication.

Discussion: PID is the acute infection of the upper female reproductive tract with typical causative microorganisms including Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoea, Mycoplasma genitalium, and anaerobes associated with bacterial vaginosis [3]. Negative nucleic acid amplification testing and culture results do not exclude PID, which remains a clinical diagnosis [1]. T vaginalis associated-PID and sepsis has been previously documented in patients with HIV [4]. Our patient was HIV (-), making this a rare case of HIV (-) trichomonas associated-PID and sepsis. Several factors delayed the diagnosis of the T vaginalis associated-PID as the cause of her sepsis, including the patient’s initial presentation, nonspecific imaging and laboratory findings, and the patient’s HIV (-) status. T vaginalis has been isolated in the upper genital tract and peritoneal cavity and is known to cause an endometrial inflammatory response that we hypothesise is an exacerbating factor in the pathophysiology of PID [1, 5]. Although the pathogenesis of T vaginalis infection is incompletely understood, several mechanisms have been proposed including the breakdown of the cervical mucosal plug and introduction of bacteria into the endometrial mucosa through the creation of punctate haemorrhage [4]. Metronidazole was added to the treatment regimen as standard of care for anaerobic and bacterial vaginosis coverage in PID to the 2021 CDC guideline [6].

Conclusions: Identification of immunocompromised HIV (+) is critical in risk stratification of T vaginalis associated-PID; however this cannot be used to definitely rule out T vaginalis as an exacerbating factor in sepsis. This case underscores the importance of maintaining a broad differential in septic patients of unknown origin and close interdisciplinary cooperation between nursing and physicians.