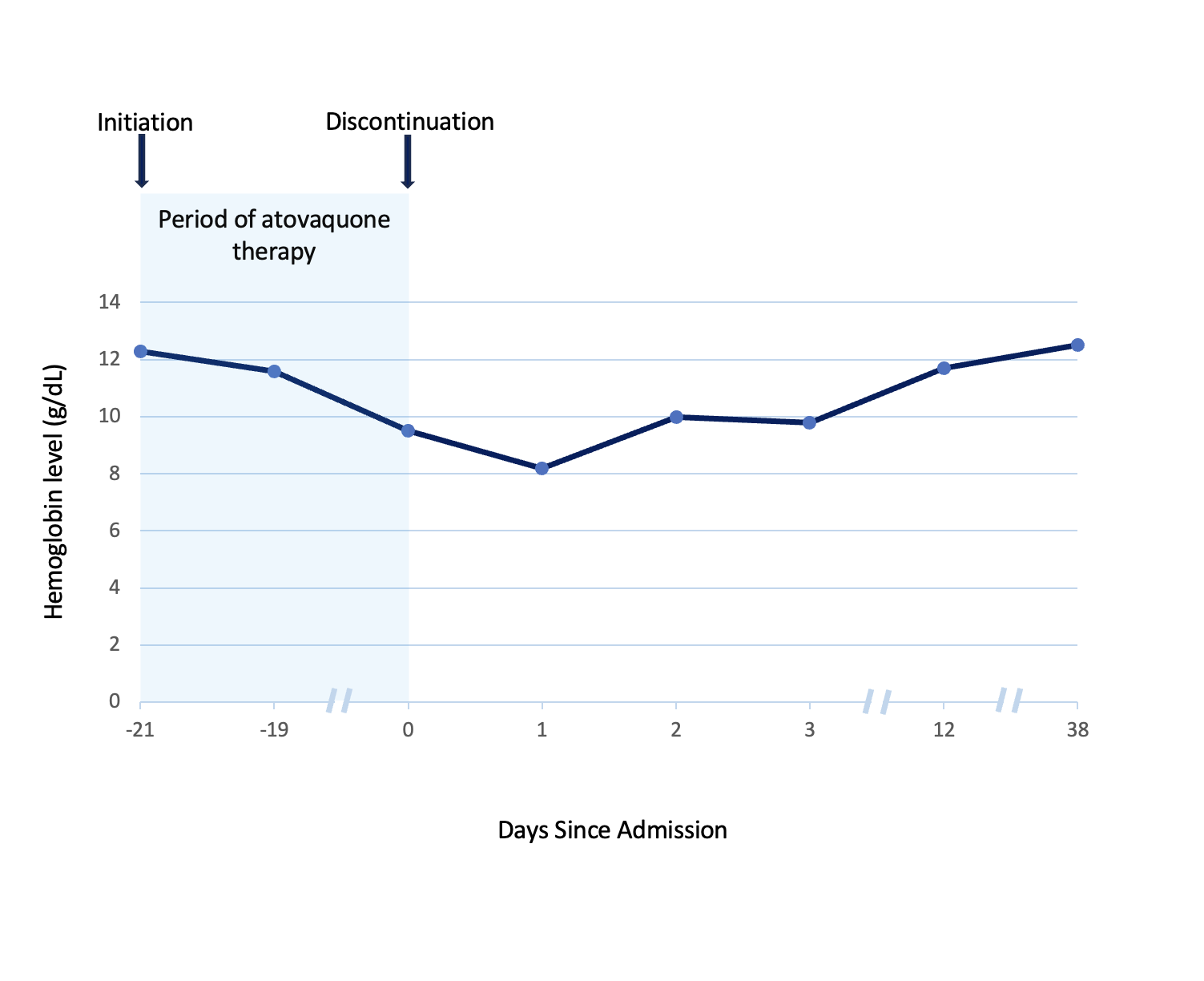

Case Presentation: A 68-year-old woman presented to the hospital with dyspnea, lightheadedness, hypoxia and no other systemic symptoms. She had a history of stage IIB small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the right lung status post chemoradiotherapy. This was complicated by radiation pneumonitis requiring long-term prednisone. Three days before presentation, she started dapsone 100mg daily for pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) prophylaxis, since her sulfa allergy precluded use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) and atovaquone was too expensive. Complete blood count, liver function and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) levels were normal before initiation. Vital signs were normal except for hypoxia (80% on room air) requiring oxygen via nasal cannula. Physical exam was unremarkable. Prednisone and dapsone were continued. Acute cardiopulmonary diseases, among other differentials, were ruled out. Due to persistent hypoxia with no clear organic source, arterial blood gas with co-oximetry was done (Fig. 1), revealing methemoglobinemia (MHb) of 16.9% and presence of a “saturation gap.” Since MHb was less than 20%, methylene blue was not given. Dapsone, the likely culprit, was discontinued and replaced with atovaquone 1500mg daily. Persistent MHb (17%) required escalation to high-flow oxygen. Subsequently, the symptoms, hypoxia and MHb improved. She was discharged on atovaquone, prednisone and home oxygen at 2L/min that was later weaned in the Pulmonology clinic. After 3 weeks, she was re-hospitalized with exertional dyspnea, fatigue, lightheadedness and palpitations. She was found to have hypoproliferative macrocytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 9.5g/dL (baseline ~12g/dL). Extensive workup regarding the etiology of her anemia returned normal. Based on this and the temporality of symptom onset, Hematology concluded that the anemia could be attributable to atovaquone. The drug was stopped and the anemia resolved spontaneously (Fig. 2).

Discussion: PCP prophylaxis in adults is preferably treated with the sulfa drug TMP-SMX. Alternatively, in patients with adverse reactions or contraindications, the main second-line agents with good tolerability are dapsone or atovaquone. Dapsone-induced MHb is typically seen in G6PD deficiency. However, our patient with known sulfa allergy developed this condition despite normal G6PD levels then atovaquone-associated anemia when therapy for PCP prophylaxis was switched. These rare adverse reactions abated with drug cessation and supportive hospital care. MHb is a potential risk with dapsone at prophylactic doses [1], even in patients without G6PD deficiency. Since MHb can be fatal (>50%), prompt recognition of signs and symptoms like dyspnea, cyanosis, refractory hypoxia and chocolate-brown-colored arterial blood with a “saturation gap” is crucial [2-3]. Management involves co-oximetry, supportive oxygen, selective methylene blue use, or ascorbic acid alongside drug cessation [2-3]. Also, though a diagnosis of exclusion, cytopenias can rarely occur with atovaquone [4]. In particular, anemia occurs in 4-6% of cases. Patients on atovaquone should be monitored and given alternatives if clinically significant cytopenias ensue.

Conclusions: Dapsone can induce MHb even at prophylactic doses in patients without G6PD deficiency and hematological monitoring for cytopenias should be considered with atovaquone. Prompt recognition of these rare associations, drug cessation and directed therapies are key steps in optimizing hospital outcomes.