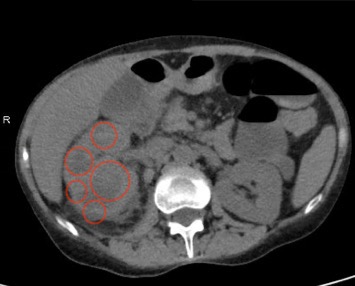

Case Presentation: A 61-year-old female with history notable for Crohn´s disease in remission presents with dysphagia associated with an unintentional 16kg weight loss over six weeks. Review of symptoms is notable for chronic diarrhea which stopped 3 days prior to admission and acute dysuria and polyuria. She is afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Initial laboratory studies demonstrate leukocytosis (16.9 x109/L), anemia (hemoglobin 6.7 g/L) and an elevated CRP (190mg/L). Urinalysis is notable for pyuria and empiric antibiotic therapy is initiated. Upper endoscopy and colonoscopy are without gross abnormalities. On hospital day two, the patient remains hospitalized without a diagnosis unifying her indolent symptoms of fatigue, weight loss and dysphagia. Her medical team revisits its initial differential diagnosis. Given her constipation, a plain film of the abdomen is obtained. It reveals a large radiopaque stone in the proximal right ureter, which leads to a computed tomography of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrating a 12 mm stone and an 8.7 cm perinephric abscess in the right kidney with replacement of the renal tissue by low density areas surrounded by an enhanced ring, classically termed as a bear paw sign. This radiographic finding is pathognomonic for Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis (XGP). While the imaging findings in this patient are representative, paradoxically, the diagnosis is confounding. XGP is an uncommon variant of chronic pyelonephritis. It preferentially affects immunocompromised middle age women with recurrent cystitis, flank pain, fever and sepsis. This pathology is never considered in the increasingly broad differentials being considered.

Discussion: Clinical decisions are multifaceted processes. Clinical reasoning research suggests that physicians apply heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to simplify complex information (e.g., pattern recognition or Type I reasoning). The representativeness heuristic allows physicians to recognize typical case of a specific diagnosis. It fails when there is an atypical presentation, particularly when the pathology is rare and the symptoms ambiguous.

Conclusions: Consistent with type I reasoning, clinicians rely on heuristics, including the representative heuristic, to make rapid diagnostic and therapeutic decisions during initial management. Here, the team relied on this heuristic for an initial differential for the indolent constellation of presenting symptoms. When the application of this heuristic failed, the team went back to the beginning to find a diagnosis satisfying the clinical picture. While the representativeness heuristic is important in practice, it should not be relied upon at the expense of an accurate diagnosis. When Type I reasoning fails, it is imperative to then apply Type II reasoning. Type II thinking is more deliberate, forward thinking and asks the question where did the hypothesis fail?