Background: Multidisciplinary rounding (MDR) is a necessary component to safe and effective patient care and discharge during hospitalization. However, there are many barriers to daily MDR that can limit the effectiveness of the team. An interdisciplinary needs assessment of MDR at our institution revealed poor communication on plan of care and limited understanding of interdisciplinary team roles resulting in lengthy MDR rounds, discharge delays and decreased perceived effectiveness of the team.The aim of this innovation was to use high-performing team principles via structured communication training and technology tools to increase the effectiveness of MDR measured by self-reported efficacy of MDR, understanding of team member roles, efficiency of MDR and finally inpatient length of stay. This high-performing team structure was piloted with one inpatient service line and then scaled up to include three additional service lines.

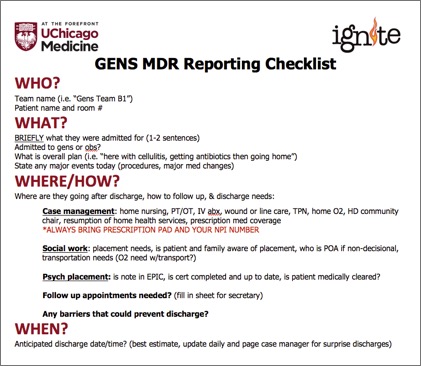

Methods: As part of our institution-wide Improving GME-Nursing Interprofessional Team Experiences (IGNITE) program, a team of internal medicine residents and a general medicine nurse manager was coached by quality improvement faculty to improve MDR. A needs assessment revealed that despite residents feeling confident in MDR presentations, overall perceived effectiveness of MDR by all staff was low (3.3 of 5 on Likert scale). Residents also reported low confidence on roles of the MDR team members (3.48 of 5). MDR was running on time (<60 min) only 48% of the time. Using high performing team principles, the interdisciplinary team developed a written script for residents to use for patient presentations at MDR. This script was printed onto badge cards to attach to ID card holders and laminated for the MDR table. To address role confusion, the team made name tent cards for MDR members with their names, roles, and pager numbers. To ensure resident teams arrived on time, standard pages were programmed for all inpatient teams to alert the start of MDR so that residents could easily remind attendings of the need to attend MDR. A virtual MDR (vMDR) in the electronic medical record was also emphasized to continue communication outside of MDR.

Results: To assess impact, post-intervention surveys were given to all MDR team members. Patient length of stay was examined using our institutional scorecard. The initial pilot on resident general medicine demonstrated an increase in perceived effectiveness of MDR by all team members (3.3 vs 4.0, 95% CI 0.05-1.23, p<0.05). Confidence about MDR team roles increased (3.48 vs 3.96, 95% CI 0.024-0.94, p<0.05). Direct timing of MDR showed MDR was more likely to be completed in <60 min (48.4% vs. 78.0%, p<0.05). In the 3-months following this change, a decrease in length of stay on resident general medicine was observed (5.74 vs 5.51 days). This model was then applied to our resident oncology, hospitalist oncology, and hospitalist general medicine service with similar results. Length of stay decreased on resident oncology services (8.08 v 6.92 days), hospitalist oncology services (7.52 v 7.18 days), and hospitalist general medicine services (7.20 v 6.23 days). Similar findings were also seen with more efficient MDR rounding on all services.

Conclusions: The creation of high-performing MDR rounds through use of structured communication and technology tools is associated with improved efficacy of MDR, increased understanding of team roles, decreased rounding time and decreased LOS.