Case Presentation: We report a case of 24-year-old male with past medical history significant for bicuspid aortic valve, epistaxis who comes to emergency department because of feeling lightheaded, generalized weakness and episode of syncope 2 weeks ago. The patient delayed seeking medical care as he had an exam the next day after he had syncope. In the emergency department his hemoglobin was 5.5. On further questioning he stated that his nosebleeds are so massive that sometimes he has to use tampons. He has been seen by ENT in the hospital in 2015 where he had septoplasty with temporalis fascia grafting and the biopsy of the septum showed hamartoma. On further lab work he was noted to have microcytosis with MCV of 58 and hypochromia MCHC of 24.8. Iron profile correlated with severe iron deficiency anemia showing very low iron of 10 with high TIBC of 455, low iron saturation of 2.2 with significantly low ferritin level of 1.0. Peripheral smear showed severe hypochromia microcytosis, and no abnormal or immature cells noted. Vitamin B12 level was 289. Hematologic evaluation for Factor VIII, IX and XIII levels were unremarkable. ENT was consulted who noted multiple telangiectasias on both sides of septum and thought he has possibly Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia/ Osler-Weber-Rendu etiology for recurrent massive nosebleed. Given the presumptive diagnosis of HHT, MRI brain was done which did not show any brain bleed, urine analysis showed no hematuria and Hemoccult was negative. He was treated with 3 units of red blood cell transfusions, iron and B12 supplements and symptomatic treatment of his nosebleeds and was discharged to follow-up to an academic center for definitive evaluation and management of hereditary telangiectasias.

Discussion: HHT is a clinical diagnosis, and the Curaçao criteria are the mainstay of diagnosis. Definite HHT is diagnosed in the presence of 3 or more features, including (1) spontaneous, recurrent nosebleeds; (2) mucocutaneous telangiectasias at multiple characteristic sites such as fingertips, lips, oral mucosa, and/or tongue; (3) visceral involvement with GI telangiectasia and pulmonary, hepatic, cerebral, and/or spinal AVMs; and (4) family history of an affected first-degree relative. If only 2 criteria are present, then HHT is possible, and HHT is unlikely if one or less criterion is present. The early presentation is usually epistaxis during childhood. It can present either as bleeding from AV malformations presenting as hemoptysis, epistaxis, Gastrointestinal blood loss, visceral/ intracerebral hemorrhage, or as aftermath of chronic bleeding presenting as severe iron deficiency anemia as explained in our case. Therefore, it is important to evaluate for rare causes of anemia if the common etiologies are not found particularly young patients.

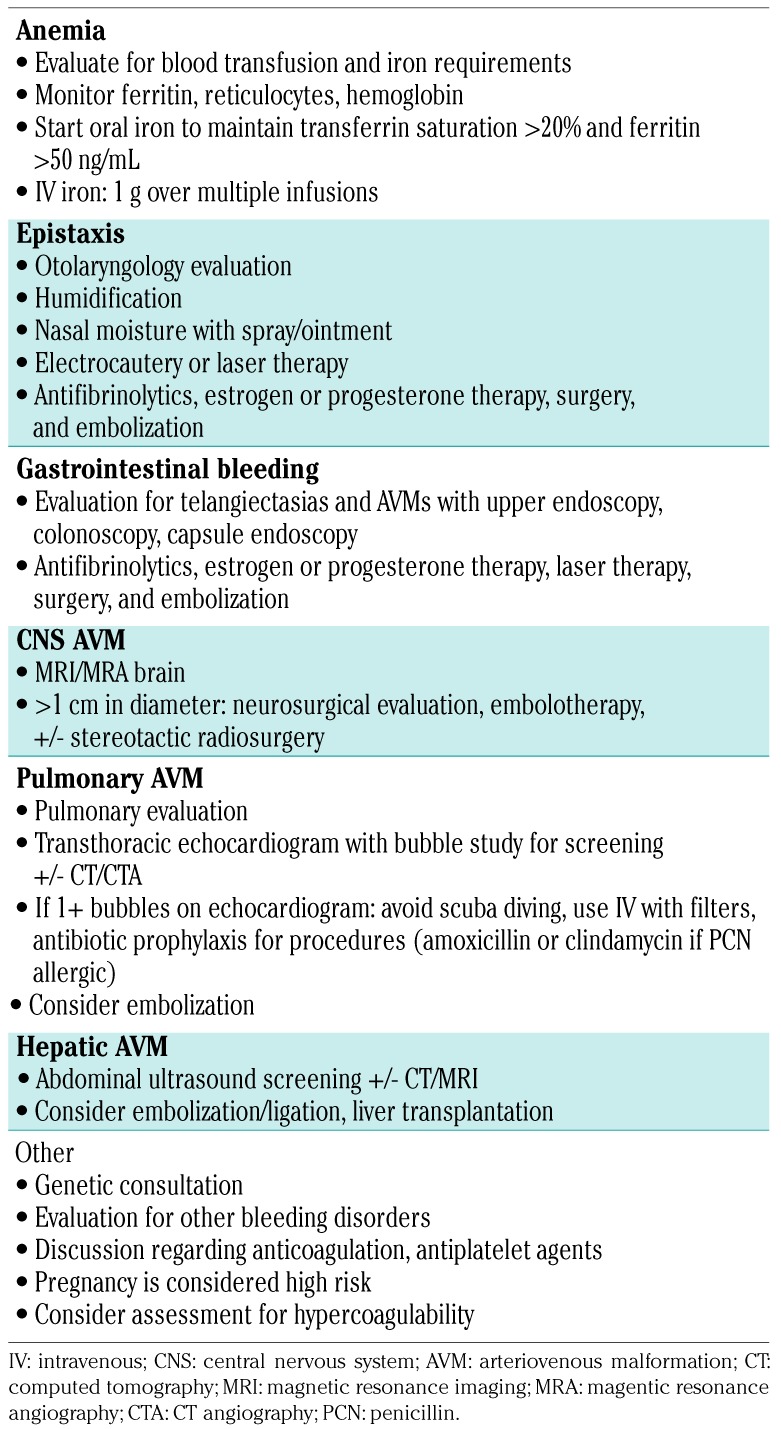

Conclusions: Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is a rare and underdiagnosed genetic disorder involving blood vessels. It has variable clinical presentations even with identical mutations which makes the diagnosis even more challenging. Therefore, it is important to evaluate for rare causes of anemia if the common etiologies are not found particularly young patients. Also due to risk of multi-organ involvement, patients with HHT should be screened for visceral arteriovenous malformations, in particular, lungs and brain which are often asymptomatic prior to the sudden development of life-threatening complications.