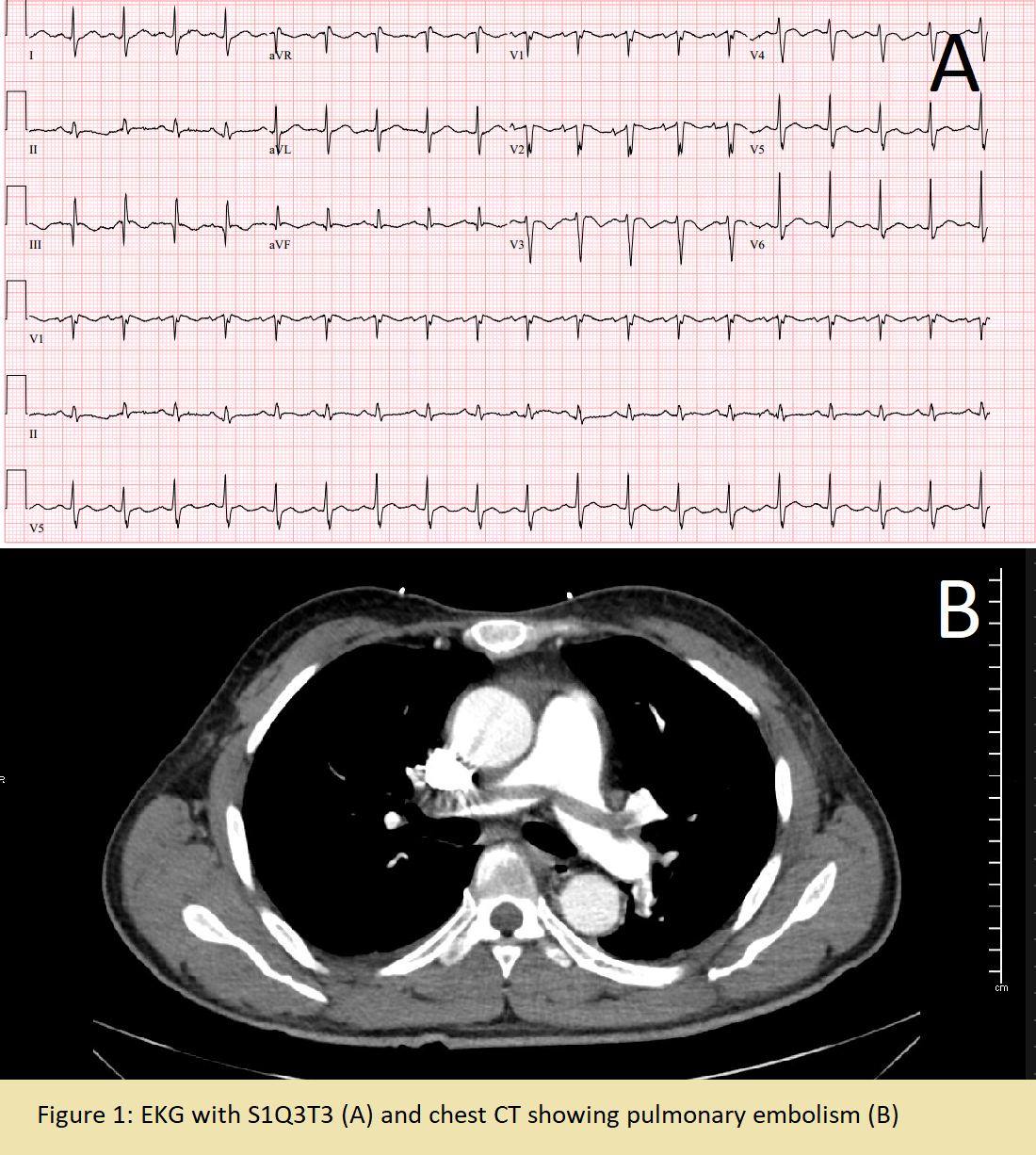

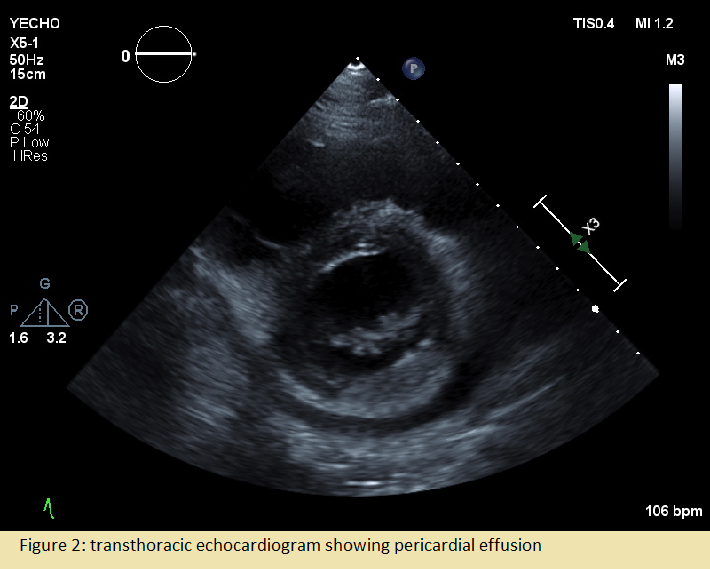

Case Presentation: A 57-year old man was found down at home one day prior to admission. Three days prior, he experienced intermittent “stabbing” chest pain and dizziness. Past medical history was significant only for multiple sclerosis treated with Copaxone. On admission, he was afebrile, heart rate 113bpm, blood pressure 104/71 mmHg, respiratory rate 19 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. Physical exam was unremarkable. Laboratory work up was significant for white blood cell count of 24,020 cells/mcL and troponin of 0.094 ng/ml. EKG showed slight ST elevation in aVR and V1-V2 with ST depression in lateral leads and he was taken for left heart catheterization which revealed nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Working diagnosis then became Type II NSTEMI in the setting of suspected sepsis of unknown source and he was started on broad spectrum antibiotics.Despite initial treatment, he continued to have severe chest pain and tachycardia. Repeat EKG was obtained and now significant for S1QT3T3 concerning for PE (Fig-1A). CTPE revealed a large saddle pulmonary embolus with extension into the segmental and subsegmental branches of the bilateral pulmonary arteries and signs of right ventricle strain (Fig-1B). He was diagnosed with a sub-massive PE with associated Type II NSTEMI. A heparin drip was started, and IR was consulted for catheter directed thrombolysis. Following thrombolysis, he was then transitioned to treatment dose Lovenox. The following day, the patient continued to have severe chest pain with tachycardia. EKG was without acute changes and repeat chest CT showed a pericardial effusion which was further evaluated with a transthoracic echocardiogram (Fig-2). He was diagnosed with pericarditis and started on NSAIDs and Colchicine. Treatment was changed to Prednisone after continued chest pain which relieved his symptoms. He was discharged on Apixaban, Colchicine, and Prednisone taper.

Discussion: Post-cardiac injury syndromes such as Dressler syndrome occur following myocardial infarction and cardiac surgery and the mechanism of these injuries is thought to be an autoimmune phenomenon. Although not well reported, there have been cases of patients presenting with pericarditis following pulmonary embolism. The mechanism is likely due to the anatomical vicinity of injury from a pulmonary embolism and hypersensitivity [1]. One single center retrospective study reported that 3.48% of 402 cases of pulmonary embolism developed pericarditis over a 13-year period [2], implying that this complication may be more common than expected. In our case, the patient continued to have uncontrolled chest pain after undergoing thrombolysis and starting on anticoagulation. Once cardiac ischemia had been ruled out, repeat imaging with a new pericardial effusion led us to consider pericarditis. Once treated as such, his symptoms resolved.

Conclusions: This case demonstrates that PE-related events and symptoms need to be recognized early as delayed diagnosis may worsen outcomes. After initial diagnosis and treatment, complications such as pericarditis should be considered.