Background: Delays in treatment of in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) events are associated with lower survival and poor neurologic outcomes (1). For ward patients on centralized telemetry, telemetry technicians notify nursing staff of life-threatening arrhythmias immediately so nursing can verify a patient’s clinical status and determine whether code blue activation is necessary. Delays in this verification lead to delays in code activation, which can, in turn, lead to increased morbidity and mortality (2). We sought to assess the impact of a bundled intervention which included empowerment of telemetry technicians to active code blues on IHCA survival.

Methods: We implemented a quality improvement protocol September 1, 2016 at our 900-bed, urban, academic safety-net hospital which incorporated 1) a telemetry hotline for telemetry technicians to reach nursing unit staff more effectively for critical arrhythmias; 2) an escalation system within the nursing mobile phone system for critical arrhythmia notifications to bump to the charge nurse if not answered within 30 seconds, then to all unit staff if not answered within 30 seconds; and 3) empowerment of telemetry technicians to call code blue directly for the following life-threatening arrhythmias: ventricular fibrillation, sustained ventricular tachycardia > 30 seconds, asystole, or bradycardia < 30 beats/minute. We performed a retrospective pre-post study of all IHCA in patients on centralized telemetry for one year prior to the intervention and three years post intervention to determine if the bundled intervention affected IHCA survival, survival to discharge and inappropriate code activation. Two-sided t-tests were used to compare continuous variables and chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables. SAS version 9.4 was used for all analyses. P-values of < 0.05 were considered significant. Telemetry technicians were also surveyed about their perceptions of the intervention.

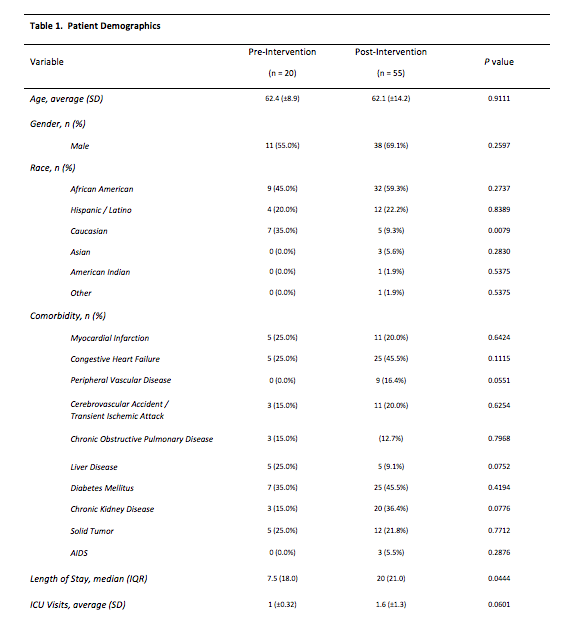

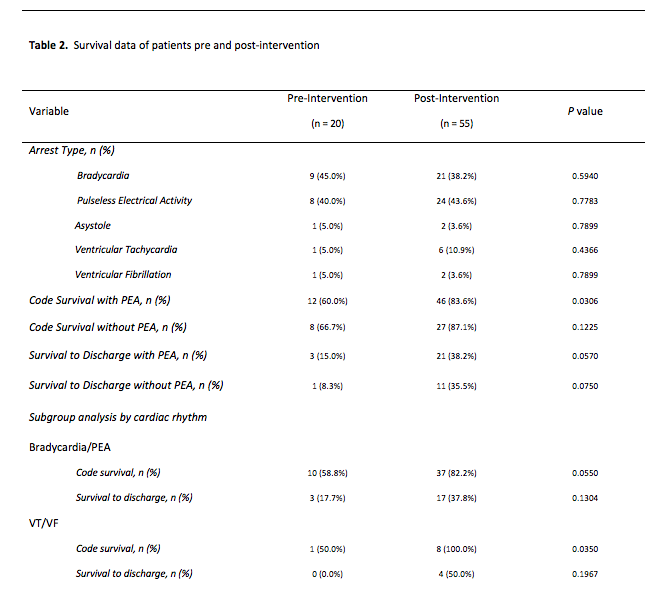

Results: Code survival was 12/20 (60.0%) pre-intervention as compared with 46/55 (83.6%) post bundle implementation (p= 0.03). (Table 2) Survival to discharge was 3/20 (15.0%) pre-intervention compared with 21/55 (38.2%) post-intervention (p= 0.059). See Table 1 for demographics. There was a significant improvement in code survival in VT/VF arrests in floor patients on telemetry (p = 0.035) though no significant change in survival to discharge (p = 0.197). There was a trend towards code survival improvement in patients with bradycardic/PEA events (p = 0.055). There was a trend towards code survival and survival to discharge with bradycardic/VT/VF arrests (p= 0.053 and p= 0.076, respectively). There were no inappropriate code activations post-intervention. Telemetry technician surveys showed a trend in perceived improvement in response time post intervention; actual code response times could not be accurately measured.

Conclusions: Our bundled intervention to expedite telemetry technician communication with bedside nursing staff for critical arrhythmias and empower telemetry technicians to directly call codes for critical arrhythmias showed a significant improvement in code survival in cardiac arrests for ward patients on telemetry and a trend towards improvement in survival to discharge. Importantly, there were no inappropriate code activations by telemetry technicians, highlighting the safety of this intervention.