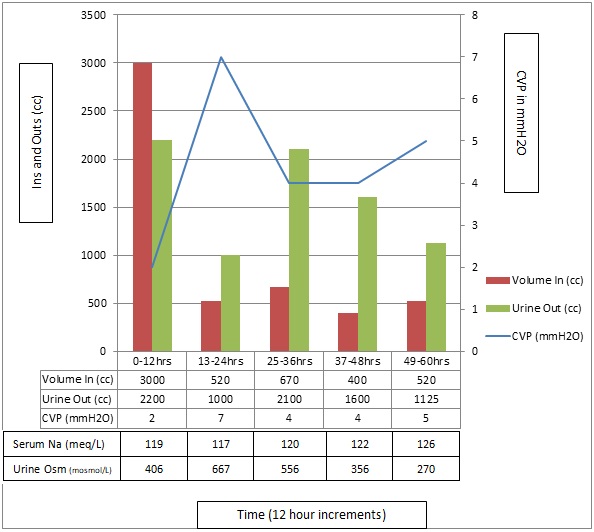

Case Presentation: A 32 year-old female without significant medical history presented with nausea and vomiting, 1 week after being a pedestrian struck by a vehicle. The original accident caused loss of consciousness, and post-concussive syndrome headaches, but no significant injuries, fractures or internal bleeding. Upon re-admission, she was orthostatic positive. She was lethargic, with a serum sodium of 119 and osmolality of 251. Notably, her urine osmolality was high at 406.

Aggressive rehydration was started, however her hyponatremia remained dangerously low. A brief course of hypertonic saline was initiated, however her sodium remained uncorrected. She urinated excessively with each hydration attempt.

Given her severe hypovolemic hyponatremia, with high urine output and sodium concentrations, seemingly resistant to rehydration, cerebral salt wasting (CSW) was considered. She was started on maintenance fluids and fludricortisone. After 3 days, her sodium and hydration status began to resolve.

Discussion: CSW is a rare etiology for hyponatremia, usually associated with neurotrauma, especially subarachnoid hemorrhage. In CSW, the kidney is unable to retain sodium, resulting in a dramatic hyponatremic hypovolemia, with high urine sodium and volume, resistant to hydration.

While this patient did suffer a previous concussion with loss of consciousness and residual headaches, no intracerebral bleed was noted. Initially, her presentation was presumed to be secondary to volume loss through hyperemesis. However, initial resuscitation with 3L normal saline resulted in 2.2L of sodium-concentrated, urine loss. Given her recent neurotrauma, syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone was entertained and hypertonic saline was started, which only exacerbated her hyponatremia.

More thoughtful consideration implicated CSW as our culprit. The patient was started on a higher dose of fludrocortisone than usually reported (0.8mg/day instead of 0.2-0.4mg/day), and maintenance-only fluids. Within 24 hours she began to improve. On day 3, her clinical mentation improved as her labs began to trend towards normal, however correction of her volume status lagged days behind. Rehydration was done slowly for fear of precipitating more hyponatremia. It is notable then, that her mentation improved with her electrolyte replacement well before return of her euvolemic status.

Conclusions: Typical causes of hypovolemic hyponatremia are gastro-intestinal and renal loss. CSW is differentiated as dramatic hypovolemic hyponatremia with high urine sodium and output, that’s refractory to typical hydration. It is most commonly found in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhages. However, this case had no brain bleeding. The treatment is fludrocortisone and observation, as this disease is usually self-limited. Of note, attempts at sodium-based rehydration can exacerbate hyponatremia. Missed diagnosis can often result in improper treatment, which poses unnecessary risk to the patient, as happened here. CSW remains a challenging diagnosis, which warrants consideration in hypovolemic hyponatremia.