Background: The primary goal of an acting internship or sub-internship is to prepare a fourth-year medical student for their intern year. At our institution, this has traditionally occurred on inpatient hospital medicine teaching teams which include senior residents, interns, and third-year medical students. Because these teaching teams are crowded with learners, our acting interns report limited patient contacts. In addition, the demand for an internal medicine acting intern experience has increased beyond typical capacity. With the expansion of our hospital medicine division, the number of non-resident teams has significantly increased while the number of resident teams has not changed, leaving many hospitalists desiring more teaching opportunities. For these reasons, we created two teams without residents, both composed of one attending and two acting interns. To determine whether students had a similar experience in this new model, we compared student course evaluations between acting interns on resident and non-resident teams to determine if there were any significant differences in student perceptions and learning outcomes.

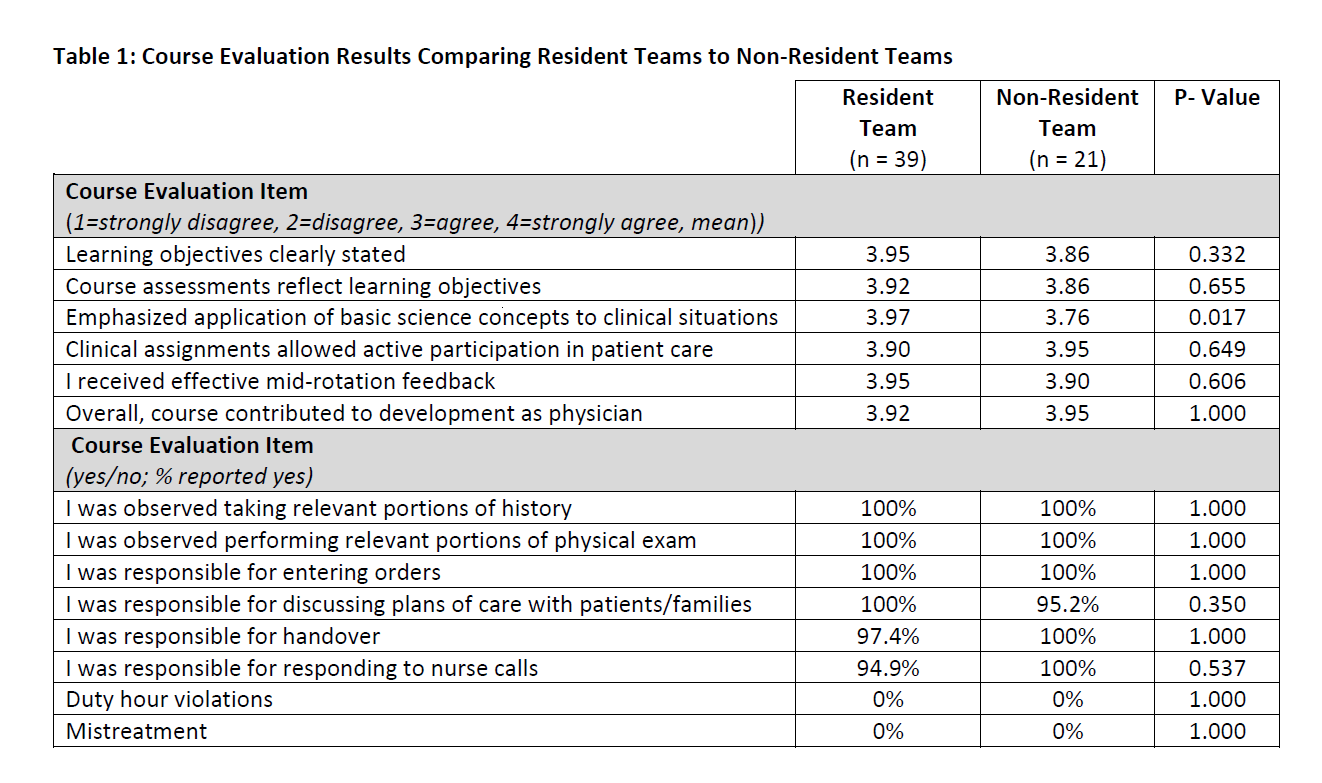

Methods: Standard acting internship course evaluations at our institution are anonymously completed by students and cover multiple aspects of the course (Table 1). They include six statements evaluating aspects of the course rated on a four-point Likert scale of 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=agree, and 4=strongly agree. Eight additional questions assessing whether a course expectation was met were answered yes/no. All enrolled students were invited to participate in the course evaluation. Results from resident and non-resident teams were compared with Mann-Whitney U test for Likert responses and Fischer’s exact test for yes/no responses. Comments from all course evaluations were reviewed for themes.

Results: Seventy-two students completed the internal medicine acting internship in the 2019-20 academic year. Sixty students completed the course evaluation (83%) including 39 on resident teams and 21 on non-resident teams with results in Table 1. The course was highly rated by students on both the resident and non-resident teams. The only significant difference between resident and non-resident teams was that students on resident teams reported more agreement that the course content emphasized the application of basic science concepts to clinical situations (p=0.017). Themes from narrative comments from both the resident and non-resident team included autonomy, clinical growth, and good preparation for intern year. Multiple comments requested expansion of the non-resident teams.

Conclusions: Acting interns on non-resident teams reported a similar experience on course evaluations when compared to resident teams. Though there was a statistical difference on the emphasis of basic science content, it is unclear why this question was different. One possibility is differing content of clinical teaching in the two teams (e.g., more robust discussion of mechanisms of disease on traditional teaching teams). This warrants further study. The overall high ratings and equivalency in the other items supports a non-resident team model as an effective option for acting interns. This model can help offload crowded teaching teams, add additional acting intern experiences, and add teaching opportunities for hospital medicine attendings. Review of narrative comments on student evaluations also shows strong support for this model.