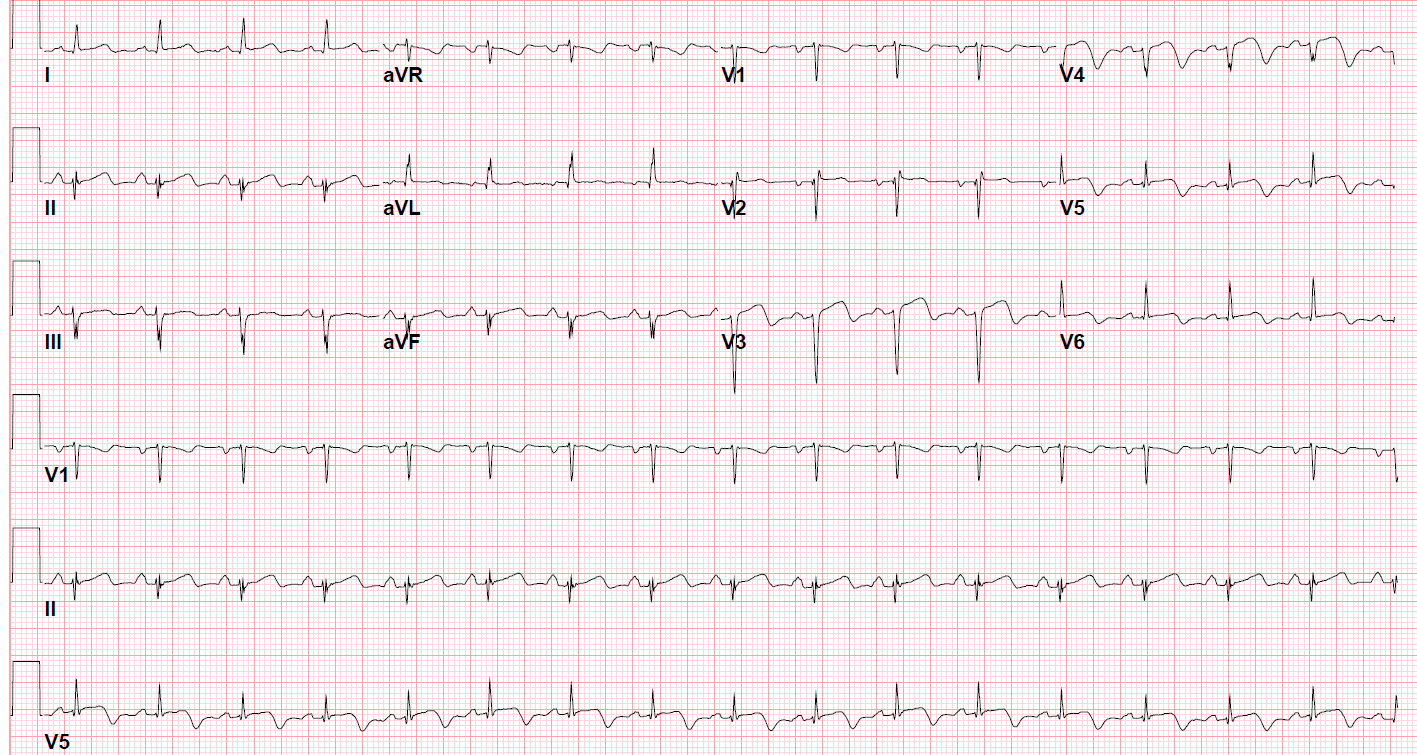

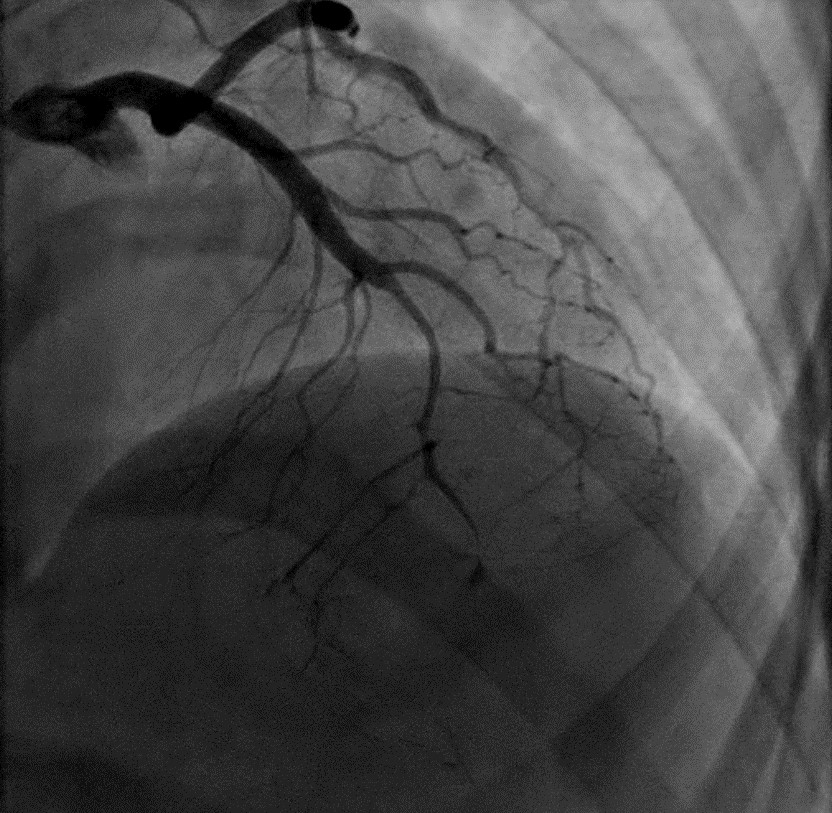

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old woman presented with 15 minutes of sharp, substernal chest pain four days after an uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Blood pressure was 158/84 mmHg, and the rest of the vitals were within normal limits. Labs and physical exam did not meet diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia. EKG and serial troponins were normal. CT scan with IV contrast was negative for pulmonary embolism. IV morphine, hydralazine, and ketorolac provided temporary relief. She was discharged with a diagnosis of musculoskeletal pain. Eleven days later, she presented with identical substernal chest pain. New ST elevations in the anterior leads were seen on EKG (figure 1). Apical and apical septal wall akinesis with an ejection fraction of 35% were seen on transthoracic echocardiogram. Troponin-T and CK-Total were 1.17 (<0.01) and 1198 (<200), respectively. A 99% mid to distal LAD segmental dissection was seen on coronary angiography (figure 2). She was treated with aspirin, clopidogrel, and 48 hours of heparin. Carvedilol and lisinopril were added for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. At discharge, reduced exercise tolerance and a mildly reduced ejection fraction were observed on exercise treadmill stress echocardiogram. She followed up in clinic two weeks later with improving exercise tolerance.

Discussion: Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is the cause for 25% of myocardial infarctions in women less than 50 years of age (compared to 4% in the general population). The majority of SCAD cases present as STEMI, NSTEMI, or a life-threatening arrythmia, but up to 7% of cases, like the one discussed here, can present as unstable angina. Affected patients do not have the typical cardiovascular risk factors. Arterial disease (e.g. fibromuscular dysplasia, systemic inflammatory conditions) and precipitating stress events (e.g. pregnancy, intense emotional stress, intense isometric exercise) are common associations. Coronary angiography, with or without optical coherence tomography or intravascular ultrasound, is used to diagnose SCAD. Pharmacological management (i.e. dual antiplatelet therapy, heparin, beta blocker, and statin if patient has hyperlipidemia) is preferred over revascularization (i.e. percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting) for most cases of SCAD. Revascularization can be considered in cases with extensive ongoing myocardial ischemia. Patients must be observed in the hospital for a few days to rule major adverse cardiac events, which can occur in up to 8.8% of the patients. An echocardiogram should be performed to evaluate for left ventricular dysfunction, and heart failure therapy should be initiated when indicated. Close outpatient follow-up should address antiplatelet therapy duration, blood pressure, smoking cessation, repeat echocardiography, extracoronary arteriopathy screening, mental health, and cardiac rehabilitation. Recurrent SCAD and myocardial infarction occur in 6-28% of the cases and vessel tortuosity is the only identified risk factor for recurrence.

Conclusions: Our case reports a subacute presentation of SCAD that evolved from unstable angina to a STEMI over the span of 11 days. Clinicians must be aware that a small percentage of SCAD patients can present with unstable angina (i.e. normal troponins and no EKG changes). A high index of suspicion can aid in reaching the diagnosis earlier and initiating therapy, which can prevent serious complications such as myocardial infarctions, fatal arrythmias, and heart failure.