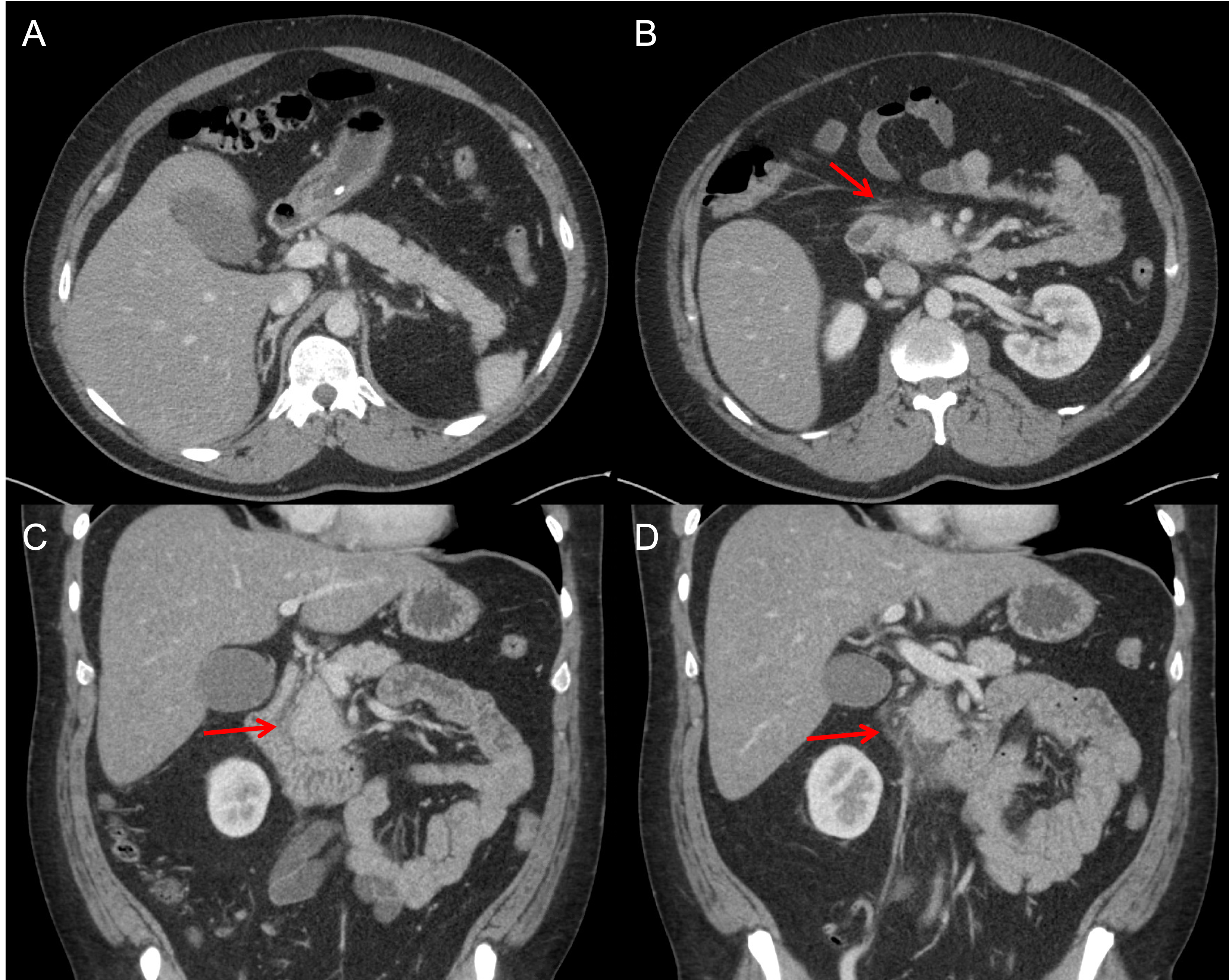

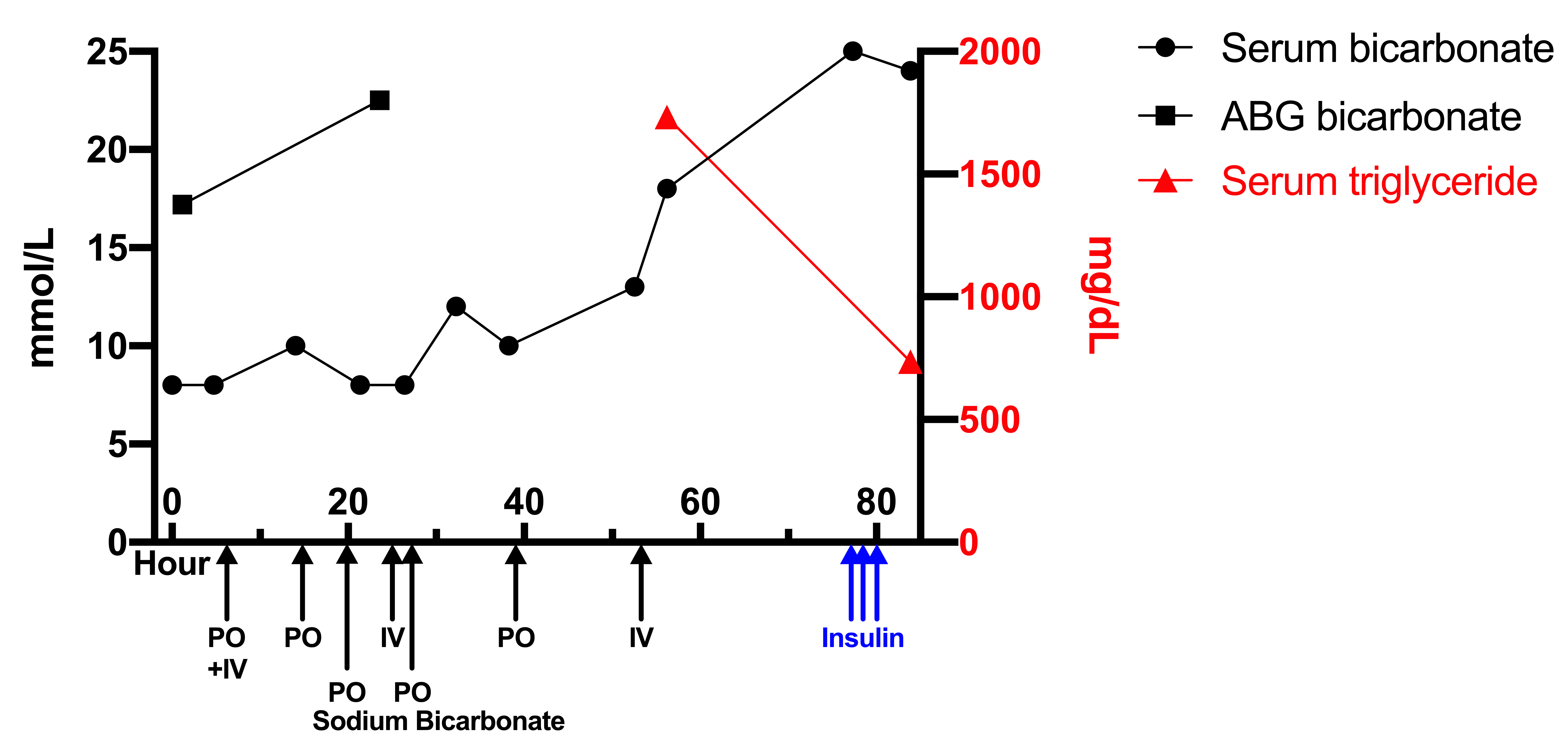

Case Presentation: A 49-year-old male with past medical history of alcohol use disorder, hypertension, and necrotizing pancreatitis presented with severe epigastric pain for one day. The pain was sharp, non-radiating, worsened by eating, and associated with nausea and diarrhea. He drinks a fifth of hard liquor daily. Pertinent labs showed bicarbonate 8 with an anion gap 27, ALT 66, AST 77, lipase 66, and ethanol 121. CT abdomen and pelvis was unremarkable. Further workup of his anion gap acidosis showed a lactic acid 2.7 and negative β-hydroxybutyrate. Arterial blood gas (ABG) showed pH 7.39 with a discrepancy in bicarbonate 17.2. Patient was admitted for alcohol withdrawal and further workup of potential acid-base disorders. He was briefly started on a sodium bicarbonate drip before transitioning to oral supplementation. Serum bicarbonate levels continued to range between 8-12 with elevated anion gaps after lactic acid normalized. Repeat ABGs continued to show compensated acid-base status with bicarbonate 22.5. On further workup, serum triglycerides were found to be elevated at 1732 mg/dL. Since the patient continued to complain of worsening epigastric abdominal pain despite conservative care, pancreatitis workup was reordered including lipase 172 U/L and the CT images showing evidence of mild fat stranding around the pancreatic head and uncinate process. Patient was treated for acute pancreatitis secondary to hypertriglyceridemia with a regular insulin drip with rapid improvement of his symptoms and reduction of his triglycerides to 735 mg/dL. Venous bicarbonate level increased to 24 and anion gap decreased to 9. He was discharged with atorvastatin and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for hypertriglyceridemia.

Discussion: While bicarbonate is demonstrated by different methods between the venous and arterial samples, it is expected that the values are within 2 mmol/L (1). A discrepancy between these two values may be due to laboratory error, excess heparin in the arterial sample (2), or an endogenous interferent, such as lipid, causing turbidity.ABG analyzers utilize electrodes to measure CO2 partial pressure, which was used to calculate bicarbonate concentration using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation. It is called “calculated bicarbonate”. On the other hand, total CO2, which occurs mostly in the form of bicarbonate in blood, was measured directly using venous blood sample by photometric enzymatic assay, hence the name “measured bicarbonate”. Since this venous bicarbonate is measured directly, it is usually more widely accepted than the calculated value. Lipid turbidity possesses a light scattering property which interferes with the light absorbance in venous blood analyzing assay (3). This phenomenon presents with low measured bicarbonate.Interestingly, our initial workup including lipase and abdominal CT, did not meet the criteria for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis on admission and the patient’s symptoms were attributed to alcohol intoxication and withdrawal. Luckily, turbidity in our patient’s venous blood samples led to pseudohypobicarbonatemia showing low measured bicarbonate, prompting a further workup of hypertriglyceridemia and potentially preventing readmission for recurrent pancreatitis and future cardiovascular events.

Conclusions: In conclusion, our case demonstrates an interesting and unique cause of pseudohypobicarbonatemia resulted from hypertriglyceridemia. As a result, this patient was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis.