Background: The “10 commandments of consultation” were published in 1983 and revised in 2007. Since then, academic medical centers have grown significantly, expanding the number of non-teaching teams. This rapid growth risks straining the current subspecialty consultation services’ teaching and educational models. Overuse of consultations and lack of clarity in the consulting question may increase length of stay and testing, while lack of clear consultant documentation delays diagnostic testing, treatment, and may endanger the transition of care. Challenges with the consultation process were identified as a top barrier to efficient patient care by Hospital Medicine (HM) and Emergency Medicine (EM) physicians at our institution.

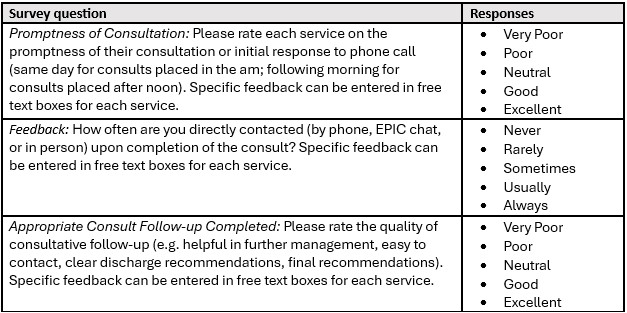

Methods: A needs assessment at University Health, a tertiary academic teaching hospital, revealed three sources of strain: feedback/responsiveness, promptness, and follow-up. We implemented a multidisciplinary process improvement project involving HM and EM leadership, departmental leadership of subspecialty consulting services, and executive leadership of our university’s physician practice to implement practice guidelines establishing the roles and responsibilities of the consulting and consultant services. A process was created for HM faculty to report deviations from the guidelines. Any recurring or egregious deviations were shared with the respective department chairs. HM and EM providers were surveyed pre- (February 2022) and post-intervention (August 2022). Survey questions used a 5-point Likert scale assessing attitudes regarding consultants’ feedback, promptness, and follow-up and provided space to enter comments (Table 1). Department specific survey results were shared with the specific department chairs. A rank list showing comparative performance of all specialties was created from the survey results and shared at a meeting of department chairs. We calculated differences in means on pre and post intervention surveys with an unpaired Welch’s t-test. We evaluated the correlation between pre-intervention scores and improvement using the Pearson Correlation coefficient.

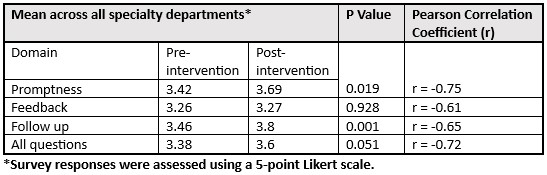

Results: Twenty-nine percent (31/107) of possible respondents completed the pre-intervention survey while 37.1% (49/132) completed the post-intervention survey. There was a significant improvement in the mean survey responses for consultant promptness (p = 0.019) and consultant follow-up (p = 0.001). There was no significant mean difference in survey responses regarding consultant feedback (Table 2). The Pearson correlation coefficient revealed a moderate to strong negative linear relationship between pre-intervention scores and improvement in scores across all questions, indicating that lower initial scores correlated with greater post-intervention improvements: all questions (r = -0.72), feedback (r = -0.61), follow-up (r = -0.65), and promptness (r = -0.75). Trauma surgery, general surgery, OMFS, Podiatry, and Psychiatry saw the largest mean improvements.

Conclusions: A multidisciplinary partnership between EM, HM, subspecialty departmental leadership, and executive leadership of our physician practice plan resulted in specific guidelines for specialty consultation and improved hospitalists’ perceptions of consultant promptness and follow-up. Specialties with the lowest initial ratings saw the largest improvement in post-intervention survey scores. These guidelines are now incorporated into the bylaws of our partner hospital.