Case Presentation: A 55-year-old male with history of bilateral degenerative hip joint disease presented for worsening serosanguinous drainage from his wounds one week after bilateral hip replacement. He further developed diaphoresis and chills and received cephalexin at an outside hospital from where he was later discharged. He did not have improvement from antibiotics and his wounds worsened, appearing increasingly inflamed, so he returned to the hospital. He was febrile to 102.9F and tachycardic on admission. Labs significant for ESR 70, CRP 14, WBC 16.3, Hgb 9. CT of his hips revealed rim enhancing discrete fluid collections. Initially, differential diagnosis included evolving abscess, diffuse edema, or cellulitis. He was admitted for concern for septic arthritis of his bilateral hips. He was started on vancomycin and cefepime and underwent aspiration of both hips. Infectious workup, including deep wound and blood cultures were negative, but the patient continued to have wound drainage and breakthrough fevers. Dermatology was then consulted who favored a diagnosis of neutrophilic dermatosis given his recent surgical procedure, fevers, leukocytosis, elevated ESR and CRP and adjacent wound with consistent appearance. His wounds were biopsied. He was started on prednisone 80 mg. Patient noted improvement in wound drainage and fevers. He was discharged on prednisone and asked to follow up with dermatology outpatient. Results of the biopsies obtained were negative for ANCA, myeloperoxidase ab, and proteinase 3 ab. Shave biopsy showed ulceration with necrosis, extensive acute inflammation and spongiosis. Punch biopsy revealed an intact epidermis with extensive ulceration and superficial dermis with marked acute inflammation and focal necrosis.

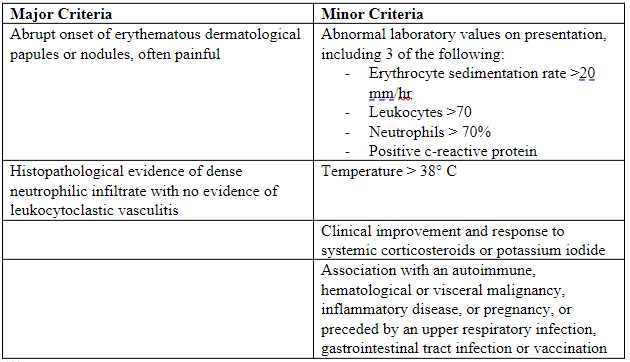

Discussion: We observed a case of NSS in a 55-year-old male with recent bilateral hip replacement surgery. Currently, the criteria to diagnose NSS should include 2 of the major criteria and 2 of the 4 minor criteria. On presentation, our patient met all minor criteria and one of two major criteria as he had sudden eruption of erythematous papules. Histology is a major criterion for diagnosis and thus, biopsy is crucial. The histopathological biopsy of the lesions in our patient did not show any evidence of neutrophilic predominance and instead revealed ulceration with marked inflammation, focal necrosis and spongiosis. The mainstay of treatment of this syndrome is oral corticosteroids (prednisone) with initial dose being 1 mg/kg/day or 40-60 mg, which can be tapered over a period of next 4–6 weeks [9, 3]. Alternatively, for patients who do not tolerate steroids, colchicine and potassium iodide can be used as a first-line therapy [14,15]. If recurrence occurs after corticosteroid treatment, other treatment modalities include potassium iodide or dapsone [3].

Conclusions: It is important to note that the cutaneous lesions found in NSS might pathologically mimic a condition called necrotizing fasciitis. However, they differ in that NSS is not caused by bacterial infections and microbial cultures are always negative. It is crucial to diagnose necrotizing fasciitis for prompt surgical debridement and broad-spectrum antibiotics [3]. On the other hand, performing such surgical interventions on patients with NSS can be devastating, often resulting in exacerbation, and further spread of lesions to involve other tissues [4]. Thus, it is essential to distinguish between these conditions to properly determine treatment options.