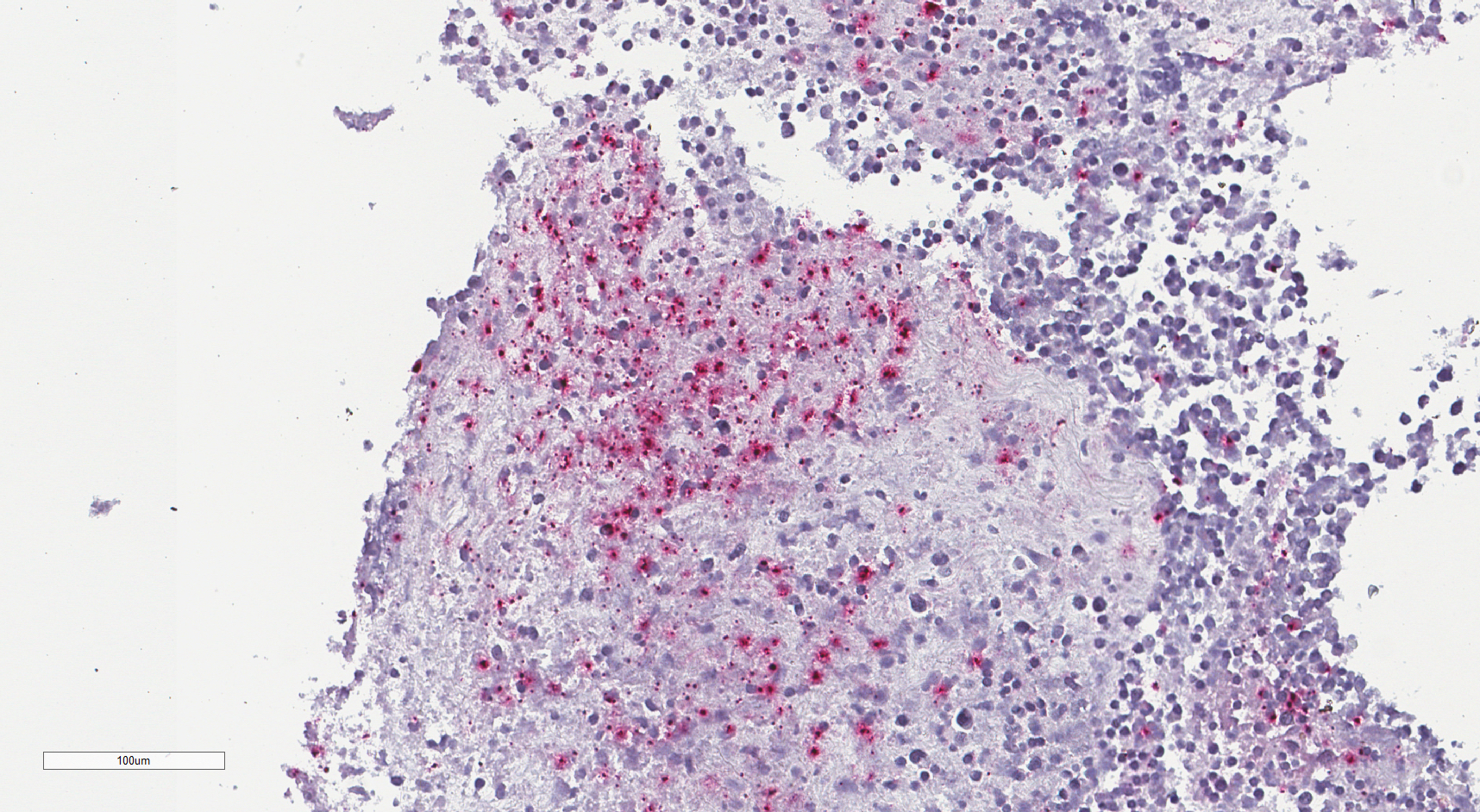

Case Presentation: A 55-year-old male with no past medical history presented with 10 days of progressively worsening generalized weakness, malaise, and night sweats.The patient, employed as a landscaper, had been mowing grass and spraying rodenticides at a rural farm 3 weeks prior. Shortly after this incident, he awoke with a constellation of symptoms including fatigue, ageusia, and sore throat, leading him to present to urgent care, where he received methylprednisolone and amoxicillin. After initial improvement, his condition deteriorated. He subsequently developed night sweats, unsteady gait, nausea, and anorexia. Five days following his urgent care visit, he presented to an outside hospital and started a course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. After failing to improve, the patient presented five days afterward to our hospital. Vitals were normal on presentation. Upon physical examination, an eschar with surrounding erythema near the left clavicle was noted along with left axillary lymphadenopathy that was painful to palpation. Initial laboratory studies revealed mild anemia (Hgb 10.9 g/dL) with normal white blood cell count (WBC 6.7 x 10^9/L), acute kidney injury due to dehydration (Cr 1.80 mg/dL), mild thrombocytosis (PLT 406 x 10^9/L), mild rhabdomyolysis (CK 307 U/L), and inflammation with ESR at 22 mm/hr and CRP at 151.5 mg/dL. Blood cultures demonstrated no growth. CT Chest Abdomen Pelvis noted prominent lymph nodes in the left axillary and left supraclavicular regions, the largest in the left axilla measuring 12 millimeters. Subsequent left axillary lymph node biopsy demonstrated a necrotic-appearing, non-malignant lymph node with marked acute inflammation. During inpatient admission, the patient’s weakness improved with maintenance IV fluids, but he experienced recurrent night sweats and low-grade fevers overnight. Despite a battery of tests, the patient’s condition remained unexplained as common infectious disease panels resulted negative. His clinical presentation, peculiar skin lesion, and history of rodent exposure urged the medical team to consider less common zoonotic diseases. The diagnosis of ulceroglandular tularemia was presumed by a positive F. tularensis antibody IgG test. Upon empirically starting a course of doxycycline, the patient demonstrated marked improvement.Sending the left axillary lymph node biopsy to the CDC added an additional layer of diagnostic confirmation. The histopathologic findings were consistent with a profound inflammatory process, characterized by necrotizing lymphadenitis and obliterated nodal architecture. Crucially, immunohistochemical staining was diffusely positive for F. tularensis, providing definitive evidence of the infection.

Discussion: This case underscores the importance of a broad differential when faced with unexplained systemic symptoms. A comprehensive patient history and careful symptom analysis are essential in steering testing toward less commonly considered conditions. Although F. tularensis infection is rare, especially among urban dwellers, it should be considered when a patient’s occupational history indicates a high risk of infection.

Conclusions: Ulceroglandular tularemia, caused by F. tularensis, is a zoonotic disease acquired through contact with infectious animal material or vectors. Its hallmark of an ulcerative eschar alongside pronounced regional lymphadenopathy necessitates targeted clinical scrutiny, particularly in those with relevant exposures or residing in endemic areas.