Background: Length of stay (LOS) is an important metric to monitor the efficiency of a hospital and is the focus of many operational and quality projects. Decreasing LOS is often made the responsibility of hospitalists and in order to identify improvement opportunities, LOS at the individual is examined. There are multiple strategies to attribute LOS to providers, but there is limited research related examining the accuracy or superiority of any given metric. Many factors related to the patient, institution, and even hospitalist group can also contribute to a patient’s length of stay. Our study aims to evaluate the significance of provider level length of stay attribution when these additional contributors are taken into consideration and how this analysis compares to more tradition attribution strategies.

Methods: The study was based on an analysis of inpatient encounters from a hospital medicine service at a large, academic, urban tertiary referral center from July 1, 2017 through June 30, 2019. For all encounters, patient demographics, including age, race, gender, and insurance status were collected. Factors considered likely to significantly contribute to LOS were also collected for each encounter, including day of week of discharge, discharging unit, hospital service, diagnosis-related group (DRG), expected length of stay, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, month of discharge, and discharge disposition. For the analysis, providers with less than 75 discharges during the study period were excluded from the analysis. For each provider, average observed to expected LOS was calculated based on discharging provider and if the provider had written any progress notes for the encounter. Discharge efficiency was also calculated for each provider based on the totality of the data set. To incorporate the additional variables contributing to length of stay into the analysis, a mixed-effects negative binomial regression model was built. Discharge destination was used as the base grouping for the model. To simplify the model, DRGs were clustered by major diagnostic category and insurances were grouped by private payor, Medicare, Medicaid, military, and other. The final mixed effects model was able to individually analyze the effect of each provider with the reference provider being the individual with most clinical encounters during the study period.

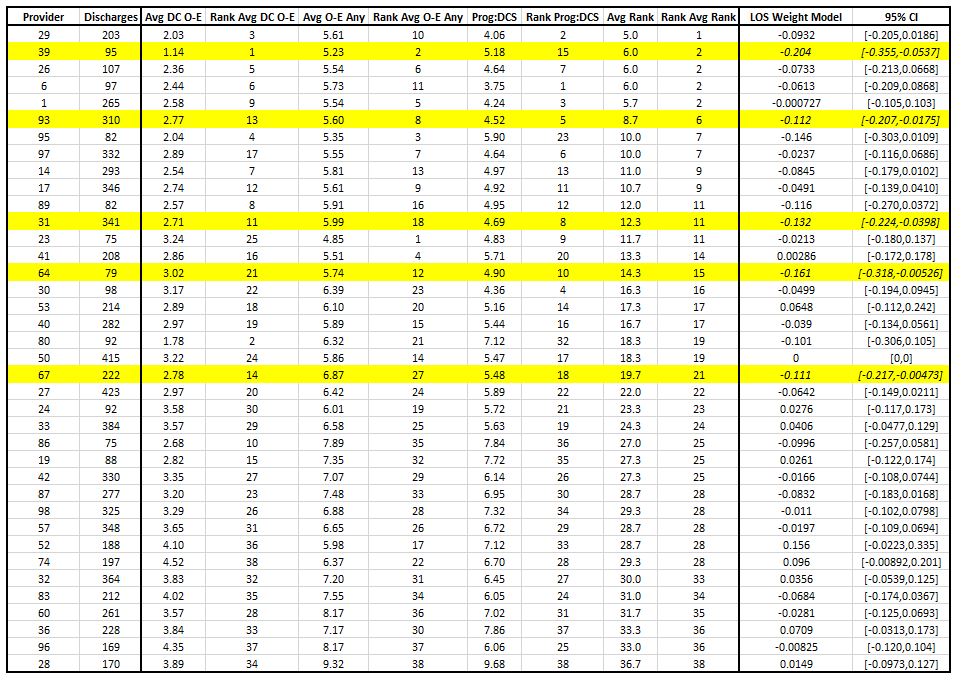

Results: A total of 70,262 patient days from 13,442 encounters were in the data set. There were 38 providers who met the minimum number of encounters to be included in the analysis, who directly discharged a total of 8369 patients. Standard LOS attribution metrics are summarized in Table 1 with providers being ranked overall based on each individual metric. In the mixed effects model, there were multiple variables that were found to be significant, including specific DRG categories, patient age, sex, insurance, discharge disposition, discharging unit, hospitalist service, and ICU stay. Of the 38 providers, only 5 were identified as contributing to significantly shorter lengths of stay (highlighted in yellow in Table 1) and none were associated with significantly longer lengths of stay.

Conclusions: In a large academic practice group covering multiple service lines, individual providers are largely unlikely to significantly contribute to a patient’s LOS. Of the few providers who were found to be significant outliers in the mixed effects model, all were high performing, and only one was clearly identified using traditional attribution strategies.