Background: Regionalization of pediatric healthcare has led to an increased proportion of hospitalizations at tertiary care centers and freestanding children’s hospitals. For some of these patients, transfer from another hospital is required to access inpatient care. There are known disparities in access to care for historically marginalized races/ethnicities, but it is unclear if these disparities are seen in pediatric transfers. Our goal was to assess the likelihood of transfer in from another facility by race/ethnicity and hospital type using a nationally representative sample.

Methods: We used the 2019 Kids’ Inpatient Database and described transfers in by race/ethnicity and hospital type using descriptive statistics. We then used a logistic regression model to assess the relationship between race/ethnicity and transfer in, while controlling for age, sex, hospital region, number of diagnoses as a proxy for patient complexity, zip code income quartile, HRISK as a proxy for illness severity, and primary payor. Using an effect modifier term, we assessed whether hospital type modified the relationship between race/ethnicity and transfer in, and finally, assessed the relationship by fitting a model for each hospital type to obtain the odds ratio.

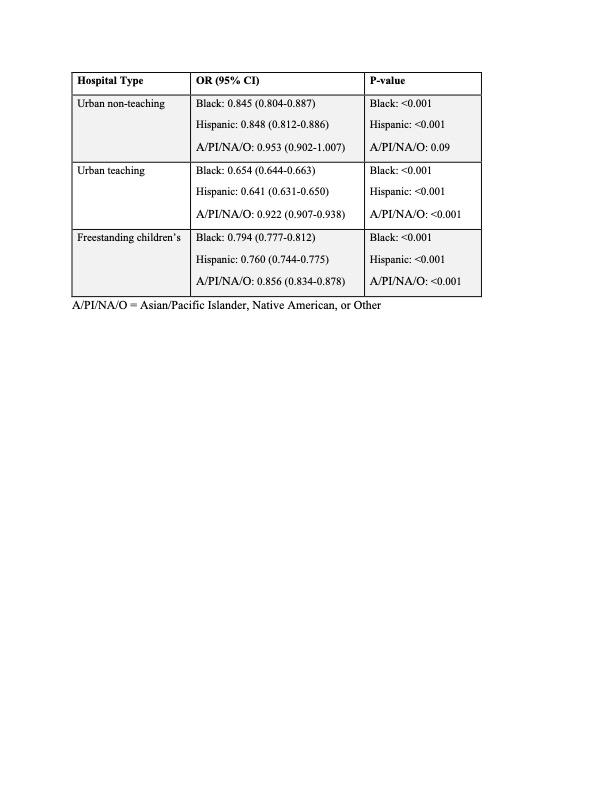

Results: A total of 333,454 encounters were analyzed. The effect of race/ethnicity on transfer in was modified significantly by hospital type, therefore results are stratified by hospital type. Black, Hispanic, and Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, and other (A/PI/NA/O) children were less likely to be transferred in from another facility for all hospital types. This was most notable for Black and Hispanic children, with odds ratios of 0.845 and 0.848 respectively for transfer in to urban non-teaching hospitals, 0.654 and 0.641 for urban teaching hospitals, and 0.794 and 0.760 for freestanding children’s hospitals. Results were statistically significant in all cases except for A/PI/NA/O children at urban non-teaching hospitals.

Conclusions: Odds of transfer in from another facility were lower for children of historically marginalized races/ethnicities in 2019 when compared with white children, who are less likely to experience inequities in social determinants of health such as healthcare access. Results may suggest that adverse social determinants of health may act as a barrier to hospital transfer for families. It is also plausible that physicians’ implicit biases could affect decisions to transfer inequitably. Further research is needed to elucidate underlying causes of these disparities.