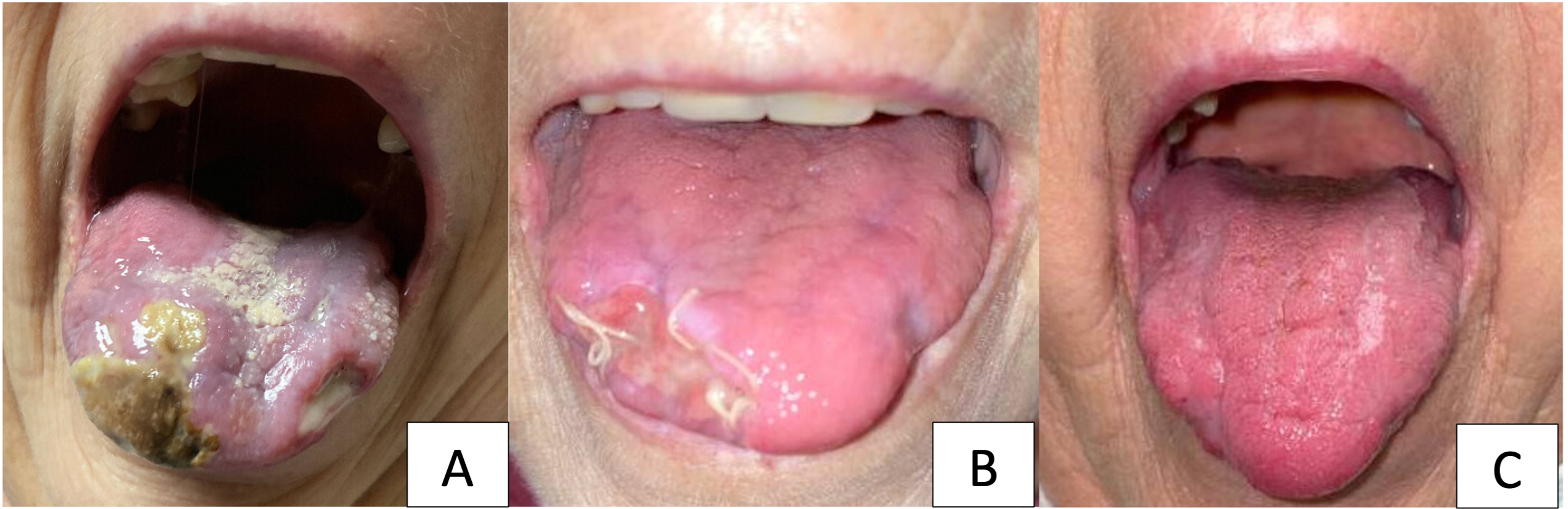

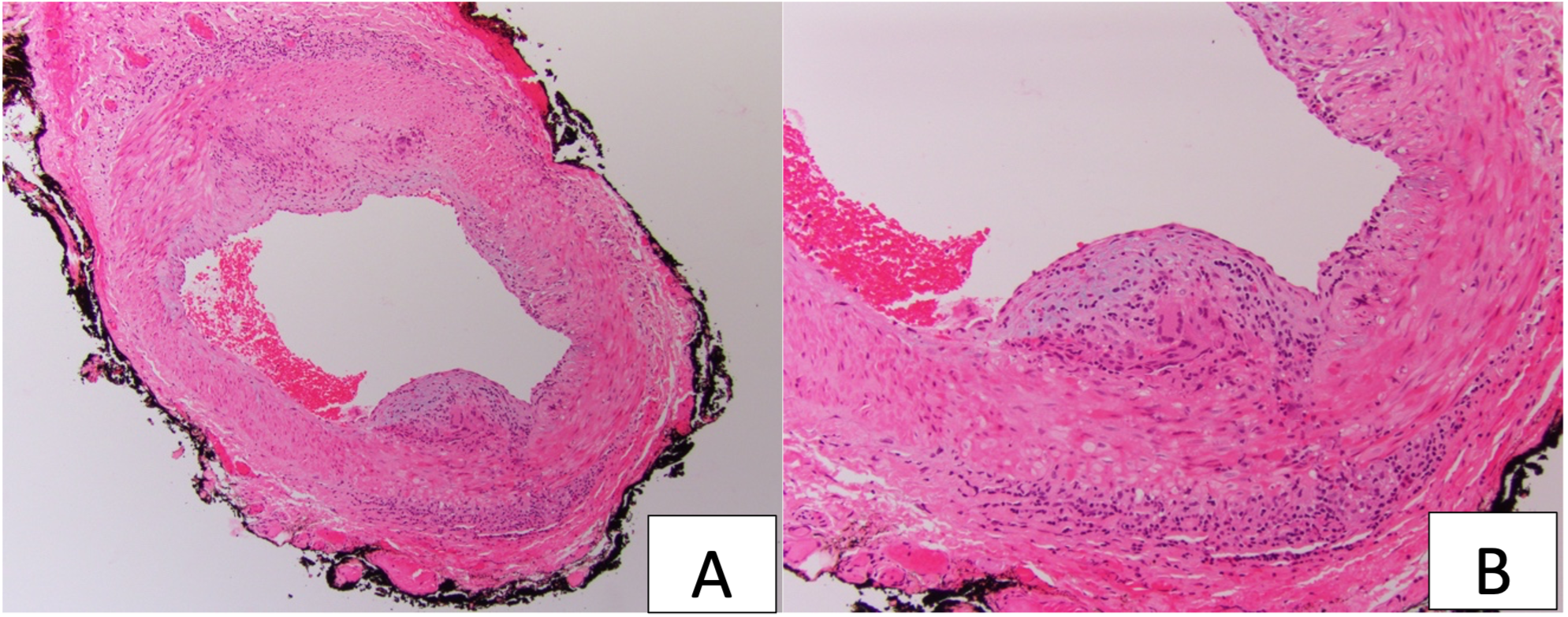

Case Presentation: Two patients developed tongue necrosis as an unusual presentation of giant cell arteritis (GCA).Case 1:A 61-year-old female presented with a one month history of painful swelling and ulceration of her tongue with weight loss. She received a punch biopsy of her tongue that showed ischemic, necrotic, and autolytic changes. After large areas of her tongue necrosed (figure 1a), she was admitted to hospital where initial work-up was normal. Literature review eventually prompted concern for giant cell arteritis. Inflammatory markers were mildly elevated with CRP at 13.6 mg/L (<= 0.50 mg/l) and ESR at 32 mm/hr (0-30 mm/hr). Right temporal artery biopsy showed lymphohistiocytic inflammation of the media, intimal thickening, and giant cells consistent with GCA (figure 2a,2b). She was started on IV solumedrol and her tongue lesions began to improve (figure 1b). She was discharged on prednisone and was started on qWeekly tocilizumab without recrudesence (figure 1c). Case 2:A 72-year-old female repeatedly presented to the emergency department (ED) for periorbital pain, diplopia, tongue pain, and glossodynia. Imaging and infectious work-up was unremarkable. ESR was elevated at 34 mm/hr (0-30 mm/hr) and CRP 9.3 mg/l (<= 0.50 mg/l). She was admitted after an acute cerebrovascular accident and developing bilateral tongue necrosis. She underwent a temporal artery biopsy that was consistent with giant cell arteritis. She was treated with IV solumedrol and transitioned to oral prednisone with plans to taper. She improved with steroids with healing of her ulcerations. She was started on qWeekly tocilizumab and had no recurrence of her symptoms.

Discussion: GCA has a prevalence of 1 in 500 individuals and commonly causes medium and large vessel arteritis [1]. GCA generally presents with scalp tenderness, aortitis, jaw claudication, and vision loss. Stroke and diplopia can rarely occur. Tongue necrosis, an uncommon manifestation of GCA, is associated with a high risk of recurrence [2]. Previous literature review identified approximately 25 cases of tongue necrosis in GCA from 2000 to 2015 with no case series reported to date [2]. This series shows two cases of tongue necrosis with pathologic evidence of ischemic etiology. These are the second and third reported cases of tocilizumab used to prevent re-development of tongue ischemia in GCA after steroid tapering shortly following the initial case published this past year [3]. This series is limited by it’s small population size, as a rare sign of a rare disease. Catheter directed angiography or deep-tissue tongue biopsy could have better clarified the pathophysiology of tongue ischemia and necrosis. Both of these patients suffered due to delay in diagnosis with worsening tongue necrosis. As an ischemic process, timely recognition is crucial to prevent rapid progression. These cases highlight the importance of having a high suspicion of GCA to initiate treatment early.

Conclusions: Here, two cases of tongue necrosis are presented in the setting of GCA where diagnosis and treatment was delayed due to their atypical presentations. Both patients had frequent ED visits and eventual inpatient hospitalization for diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, patients above the age of 50 presenting with tongue pain or ulceration should prompt consideration of GCA.