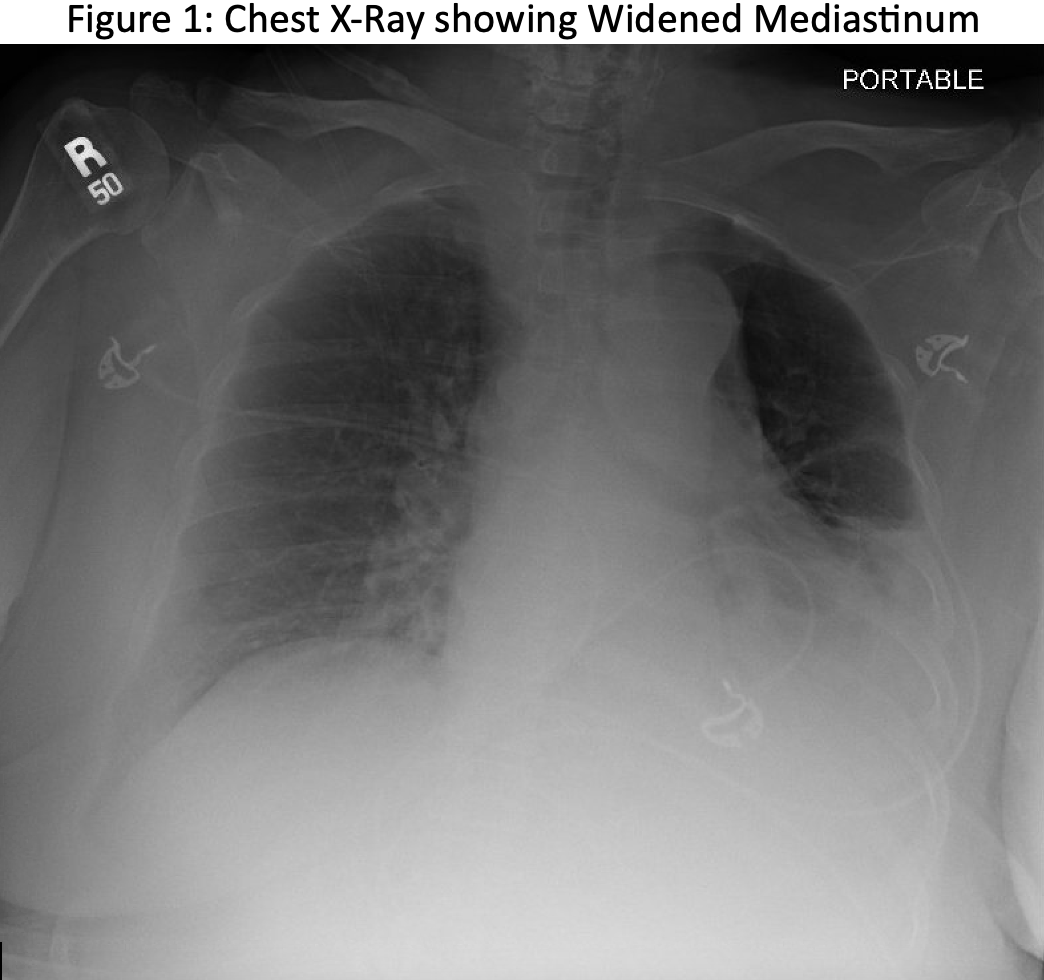

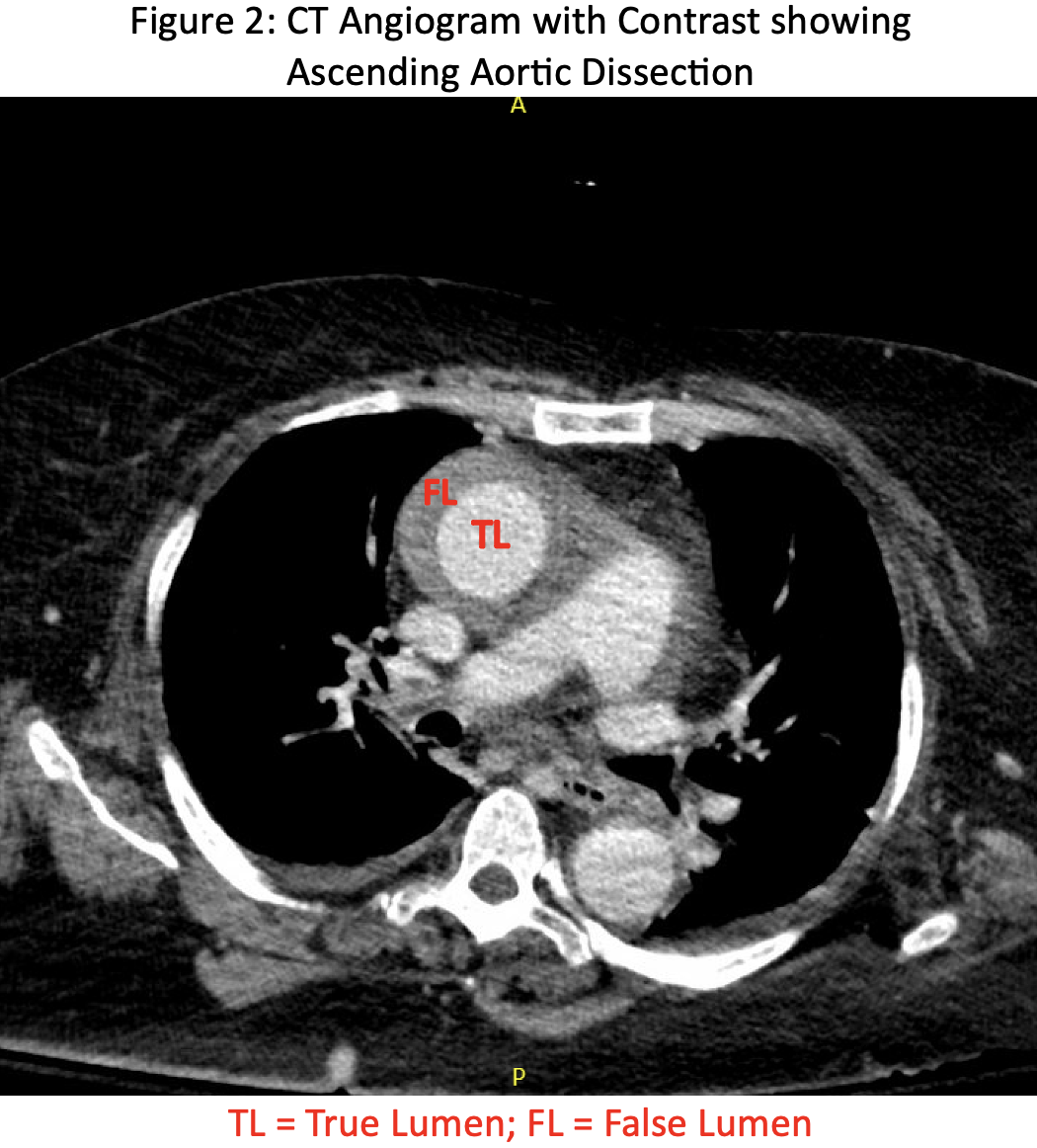

Case Presentation: A 63-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes, multiple strokes with residual left sided deficit, and chronic kidney disease, who presented with altered mental status (AMS) after losing consciousness for 20 minutes during which family noticed left sided facial droop and dysarthria. The patient denied chest pain and shortness of breath and had no known anginal equivalent symptoms. On exam, vital signs were stable, she was alert only to herself, and she had new left gaze deviation and dysarthria with unchanged left sided weakness. CT head without contrast and MRI brain were negative for acute stroke. EEG was negative for seizure. Pertinent labs included lactic acid of 2.7 mmol/L, creatinine of 2.1 mg/dl with unknown baseline, and high sensitivity troponin of 38 ng/L. Troponin up trended and peaked at 3,414 ng/L. A few hours after admission, ECG showed new T wave inversions compared to initial ECG, which suggested non-ST segment myocardial infarction type 1 versus 2. Cardiology was consulted and the patient was started on heparin infusion. On further cardiac work-up, transthoracic echocardiogram showed moderate pericardial effusion, preserved ejection fraction, and no wall motion changes. Repeat chest X-ray showed a widened mediastinum and pulmonary edema (Figure 1). CT angiogram confirmed Type A ascending aortic dissection with hemopericardium (Figure 2), and heparin infusion was stopped. Cardiothoracic surgery was consulted and advised non-operative management due to poor prognosis, and the patient was transitioned to outpatient hospice care.

Discussion: Acute type A aortic dissection is a tear in the intima or the innermost layer of the ascending aorta, creating a pseudo lumen that can compress the true lumen (1). Life-threatening complications of Type A aortic dissections include cardiac tamponade, aortic rupture, stroke, aortic regurgitation, congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction (2). Thus, type A aortic dissection is a surgical emergency which needs swift diagnosis and treatment (3). In the International Registry of Aortic Dissection, 85% of patients initially presented with acute onset tearing chest pain (4). Up to 30% of patients are initially misdiagnosed (5). We describe an atypical case of type A aortic dissection that was painless and initially presented with altered mental status.

Conclusions: Type A aortic dissections are surgical emergencies and may have atypical presentations which can delay diagnosis and life-saving treatment. Neurological symptoms in aortic dissection occur due to propagation of the dissection proximally or distally to the initial tear with involvement of the aortic branch arteries, or due to mass effect as the expanding aorta compresses surrounding structures (6). In our patient’s case, the clinical presentation along with laboratory and ECG findings warranted initiation of anti-coagulation in the setting of possible ACS, however this later became contraindicated after discovery of the aortic dissection with hemopericardium. This case highlights the challenge and importance of distinguishing type A aortic dissection and ACS, especially when considering initiation of anti-coagulation. Despite the relatively low frequency of AMS (10%) and focal deficits (15%) occurring in patients with aortic dissection (7), providers should have high clinical suspicion for aortic dissection in patients with unexplained AMS and suspected ACS even in the absence of classic tearing chest pain.