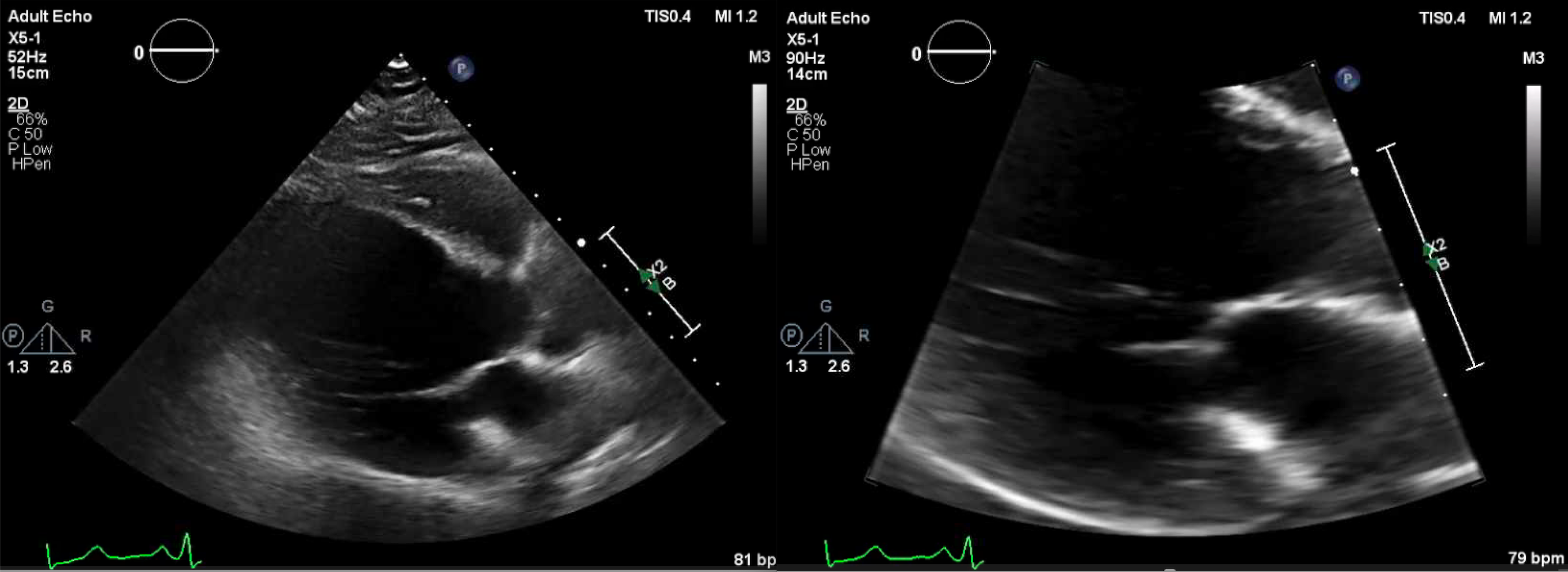

Case Presentation: A 55-year-old male with a history of coronary artery disease, left ventricular (LV) mural thrombus, tobacco use, and recent thalamic, splenic, and renal artery infarcts, presented with two weeks of worsening pain and cyanosis of his left third and fourth toes, associated with claudication. He denied numbness or loss of strength. He denied recent trauma but admitted to not being compliant with outpatient aspirin and warfarin use. Vital signs were normal. On exam, he had duskiness to the distal left third and fourth toes, weak dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses, and delayed capillary refill. Laboratory studies were notable for WBC 14/mm3, hemoglobin 18 g/dL, platelets 594, 000/uL, PTT 41 seconds, and INR 1.2. Hypercoagulable state showed primary polycythemia vera (PV), given low EPO level and positive Jak2 mutation. ANA and dsDNA levels were negative. Echocardiogram showed LV thrombus extension, which increased to 4 cm. CT coronary arteries showed filling defects along the walls of the aortic arch and descending thoracic aorta. Left lower extremity vascular studies were normal.

Discussion: The intriguing nature of our case is that our patient’s progressively worsening pain and cyanosis of two left toes were due to two processes: hypercoagulability from PV and embolization from a large LV thrombus. Blue toe syndrome is usually due to upstream atherothrombotic embolization, direct trauma, thrombosis due to peripheral vascular pathology, systemic hypercoagulable disease, autoimmune disease, or malignancy. Echocardiography is the initial approach as cardiac origin accounts for >50% of small vessel occlusion events. Our patient’s large, mobile, LV thrombus and history of downstream, splenic and renal arterial infarcts support the suspicion of cardioembolic disease. His unremarkable non-invasive vascular studies point away from peripheral artery disease as an etiology. Given his negative ANA and dsDNA levels, it was less likely he had an autoimmune cause.PV leads to blue toe syndrome due to platelet-mediated inflammation and thrombosis seen with concomitant thrombocythemia. Clinical presentation manifests as initial erythromelalgia with progressive acroparesthesia and ischemic necrosis. Low-dose aspirin and regular phlebotomy can provide symptom relief, along with hydroxyurea to reduce hyperviscosity burden. Our patient was treated with aspirin and hydroxyurea and plans for weekly, outpatient phlebotomy for PV. He was resumed on warfarin for his mobile LV thrombus. The patient was motivated to be compliant with this plan due to the significant morbidity he had and possibility of his symptoms worsening if he was non-adherent.

Conclusions: Though Occam’s razor is often encouraged, it is important to consider multiple etiologies in blue toe syndrome since results could impact management. Hospitalists are key in navigating the thorough diagnostic workup and in counseling patients on the perils of medication non-compliance to decrease risk of morbidity of blue toe syndrome.