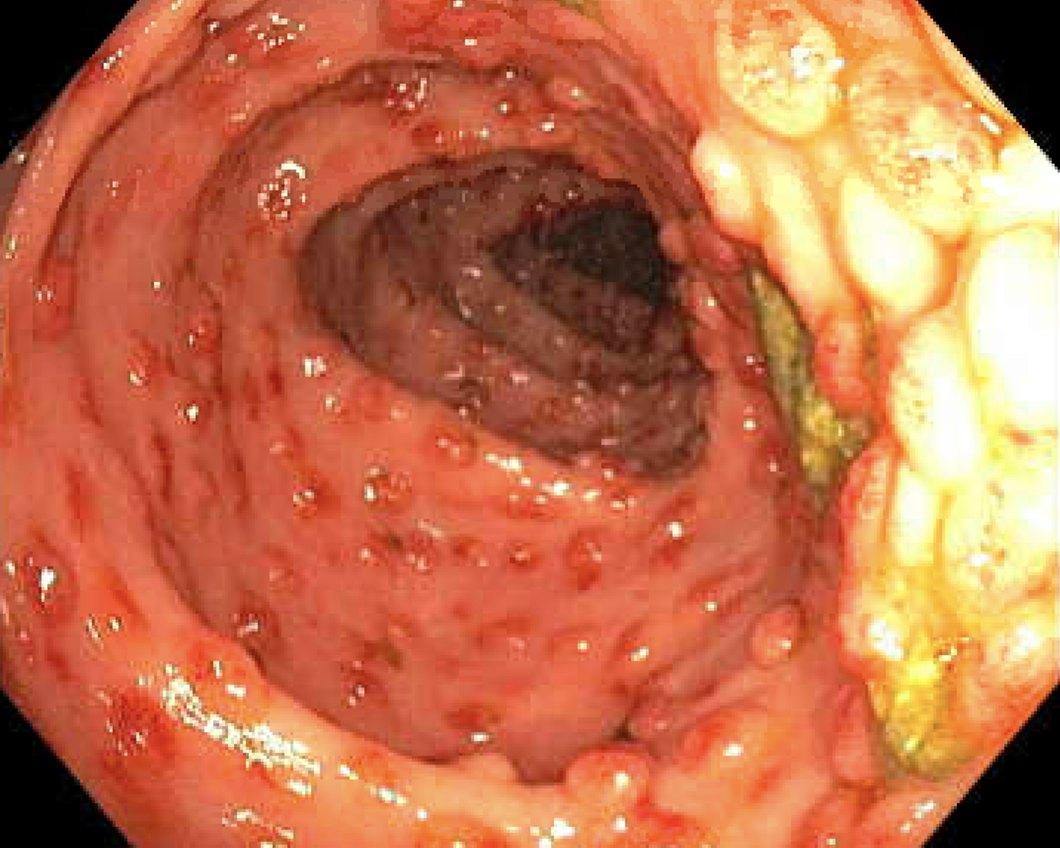

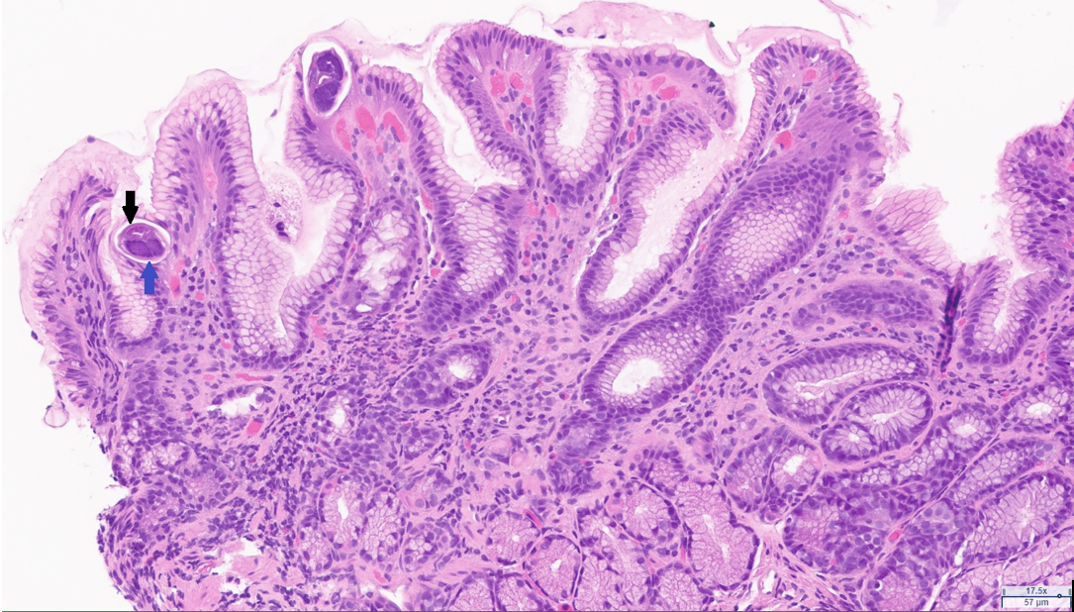

Case Presentation: A 71-year-old patient with a past medical history of hypertension, insulin-dependent type two diabetes mellitus with peripheral neuropathy, and deceased donor kidney transplant two years prior (CMV D-/R+ & EBV D+/R+) presented with a complaint of acute onset dark urine, and progressively worsening nausea, vomiting, and intermittent diarrhea. His immunosuppressive regimen consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. He had been using metoclopramide for his GI symptoms for a presumed diagnosis of diabetic gastroparesis without resolution. Review of systems was positive for a persistent dry cough. On presentation, he was afebrile, with an unremarkable physical exam. Lab work was significant for chronic hyponatremia initially at 124, and low-level CMV viremia. Urine culture grew E. Coli, and he was treated for a urinary tract infection (UTI). An inpatient EGD revealed a grossly normal appearance of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, and colonoscopy findings of erythematous polypoid lesions were seen carpeting the entire colon from 30cm onward (FIGURE 1). Biopsy confirmed CMV colitis by immunohistochemical staining. Many Strongyloides sterocalis were present in the stomach, duodenum, and colon (FIGURE 2). As this patient was a native of Puerto Rico, he was screened for Strongyloidiasis before his kidney transplant, was found to have positive IgG titers, and was prescribed a course of Ivermectin. However, the patient admitted to not completing his prior full course of treatment after receiving his current diagnosis. Treatment was initiated with oral ivermectin 15mg daily for two weeks for strongyloidiasis. Treatment for CMV was initiated with IV ganciclovir 5mg/kg every 12 hours before transitioning to valganciclovir 900mg twice daily for a total duration of treatment of 30 days. The patient’s nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea resolved with completion of therapy.

Discussion: Renal transplant recipients often present with a myriad of complications due to immunosuppression and underlying health conditions [1]. Parasitic infections endemic to the United States are rare, but Strongyloidiasis is found in the southeastern region [2]. Currently, there is a growing awareness of the necessity to consider parasitic infections in the transplant process, notably strongyloidiasis, which can cause chronic and often asymptomatic infections, that may reactivate under immunosuppression. It has been shown that immunocompromised individuals, particularly if medicated with corticosteroids, are at an increased risk of parasite autoinfection despite prior treatment as a single surviving larvae would be able to continue multiplying. This puts transplant recipients at increased risk for strongyloidiasis hyperinfection syndrome [3]. For the treatment of disseminated strongyloidiasis, it is suggested that daily treatment may be beneficial until stool studies are negative for two weeks which is the duration of a cycle for autoinfection [4].

Conclusions: Hospitalists often manage transplant patients and must be aware of atypical presentations of post-transplant infections and consider these in the differential diagnosis with non-resolving symptoms. We elected to pursue additional work up given his immune suppression and persistent symptoms. Managing transplant recipients with multiple comorbidities requires a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach as in our case with engagement of Infectious Disease and Pathology.